- P-ISSN 2799-3949

- E-ISSN 2799-4252

The emergence and development of Daesoon Jinrihoe in the late 19th century on the Korean Peninsula have placed it as a significant modern religious tradition in contemporary Korea. In consideration of its origin, roots of Daesoon Jinrihoe are found to be tightly connected to both the formal and material contents of diverse Eastern and Western religious traditions. The purpose of the current study is to explore the social background of Daesoon Jinrihoe and unveil its strong bond and relationships with other world religions and systems of philosophical thought. Additionally, it seeks to examine the distinctive features of Daesoon Jinrihoe, assessing whether it remains as a New Religion or has already qualified its status as an established religious tradition, akin to major world religions. In terms of research methodology, this study employs a discourse analysis approach within a qualitative research framework. Secondary sources are utilized extensively, supplemented by primary sources that are necessary and mandatory for a comprehensive understanding.

The emergence and development of Daesoon Jinrihoe in the late 19th century on the Korean Peninsula have placed it as a significant modern religious tradition in contemporary Korea. In consideration of its origin, roots of Daesoon Jinrihoe are found to be tightly connected to both the formal and material contents of diverse Eastern and Western religious traditions. The purpose of the current study is to explore the social background of Daesoon Jinrihoe and unveil its strong bond and relationships with other world religions and systems of philosophical thought. Additionally, it seeks to examine the distinctive features of Daesoon Jinrihoe, assessing whether it remains as a New Religion or has already qualified its status as an established religious tradition, akin to major world religions. In terms of research methodology, this study employs a discourse analysis approach within a qualitative research framework. Secondary sources are utilized extensively, supplemented by primary sources that are necessary and mandatory for a comprehensive understanding.

Mohammad Jahangir Alam, PhD is a Professor and Chairman of the Department of World Religions and Culture at the University of Dhaka, where he earned his MPhil and PhD. A specialist in Bahá'í and Cao Dai Faiths, he authored "The Concept of Unity in Baha'i Faith and Caodaism: A Comparative Study" (2010) and edited "World Religions and Culture: Interfaith Education in Bangladesh" (2022). Having published 22 research articles and four book chapters, his current research focuses on identifying common aspects of truth in religions to foster peace and harmony, and exploring social integration of New Religious Movements (NRMs). He received several awards, including the Cao Dai Overseas Missionary (CDOM) U.S. Fellowship Award in 2012 at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Historically, no form of social turmoil—whether religio-cultural or politico-economic—has gone unchallenged (Ahmed 2009). During periods of tension, resistance movements often emerge in various forms, aiming to counter the hegemonic dominance of established organizations. Korea, for example, have faced numerous challenges and undergone significant changes since Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953), with none of these events going unchallenged because various religious movements emerged alongside many other forms of resistance. In the middle of social chaos (Yongbok 2018) new Korean religions started to emerge. This dynamic created the potential for new religious movements to arise, challenge mainstream religions and encourage marginalized groups to break away and establish reformed or new movements. Throughout history, new religions have often stemmed from mainstream traditions to pursue new aims, objectives, and ideologies. The era of Cold War globalization also encouraged religions to adopt new, revised, or reformed social, moral, and political agendas (Hartney 2022). Daesoon Jinrihoe is an example of a new religious movement that was officially established and developed during the era of Cold War globalization. Its predecessor movement emerged on the Korean Peninsula in 1901 through Kang Jeungsan, inheriting ancient traditions and modern ideologies shaped by interactions with anti-colonialist nationalist politico-religious movements. Although Daesoon Jinrihoe is a new religion, it is deeply rooted in traditional religions that arrived in Korea during various periods of antiquity. Confucianism, for example, along with Chinese characters arrived on the Korean Peninsula around the beginning of the Christian Era. Buddhism arrived in 372 AD during the formative period of the national system in Korea, and Daoism was introduced in 624 AD during the Tang Dynasty of China. History attests to the harmonious coexistence of these traditions, including Korean folk religions, from the Goryeo to the late Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897). This harmonious coexistence is clearly manifested in Yoon Yongbok's (2018) observations on Korean religions and culture. Daesoon Jinrihoe is an Asia-centric homogeneous tradition and the largest indigenous Korean new religion (Chryssides 2022). It has incorporated borrowed elements into its own practices without losing its cultural identity. Similarly, the Vietnamese origin of Cao Dai represents a harmonious synthesis of both Eastern and Western elements without losing its native identity (Alam 2020).

Following Kang Jeungsan (Sangje or Supreme God), his two successors, Jo Jeongsan (Doju or Lord of the Dao ) and Park Wudang (Dojeon or Leader of Principle), played pivotal roles in successfully fulfilling the divine mandate (Chong 2016). However, the success story of Daesoon Jinrihoe faced numerous challenges and difficulties. In this context, it should be noted that in addition to the Japanese colonialism from 1910–1945, Jeungsan-related religions had to face the Korean War from 1950–1953; a Buddhist-backed political regime from 1962–1979; and a succession of authoritarian regimes from 1948–1987 that mobilized a strong civil religion for political purposes. It is reportedly true that, just before significant changes in Korean culture occurred, the culmination of Daesoon Jinrihoe’s formal founding occurred in 1969. Its full-fledged development took place during this period of cultural change. According to Don Baker ((2001)), subsequent changes continued taking place over the last four decades since 1971, and he deemed these to be dramatic and significant transformations in Korean culture. Amid these changes, Daesoon Jinrihoe emerged as a prominent New Religion in Korea. At this point, it is crucial to highlight the current situation of Daesoon Jinrihoe in modern Korea before examining its linkages with other religions. Therefore, before exploring the relationship between Daesoon Jinrihoe and other religions, the concept of New Religious Movements (NRMs) and Daesoon Jinrihoe should be reexamined from both global and Korean perspectives. This includes understanding the academic focus on Daesoon Jinrihoe, evaluating its position as a new religion, assessing its progress and influence, and then briefly looking at its connections with other religions.

In this section, the concept of "new religions" based on Henry Van Straelen's (1963) analysis will be reassessed to understand the position of Daesoon Jinrihoe in terms of its classification through via the comparative lenses of both Western and Eastern scholars. When grappling with the term "New Religions," one often encounters the challenge of terminology or delineation. Straelen's exploration sheds light on this issue, revealing that it hinges on fundamental questions concerning the notion of "new," a term inherently relative in nature. These questions include: Temporally, what constitutes "new"? At what juncture does "new" transition into "old"? Conceptually, when does a body of doctrine or an organization qualify as a new religion rather than a sect within a larger religious tradition?However, further inquiries emerge concerning Daesoon Jinrihoe: Under which precise classification does Daesoon Jinrihoe fall? Should it be categorized within Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism? How does it relate to other religions? Traditionally, the Judeo-Christian heritage has been regarded as one of the principal sources of new religious movements. Alongside this, the nebulous realm of nonofficial religious practices or the cultic milieu is also acknowledged as a wellspring of New Religions. The Judeo-Christian tradition, with its inherent proclivity for cycles of renewal, reform, and schism, has been particularly influential in shaping new religious movements in the Western context. While many new religions draw inspiration from the cultic milieu in terms of ideas and ritual practices, they distinguish themselves by organizing these elements into coherent structures.Notably, some new religious movements claim antiquity, asserting origins predating historical religions such as Christianity. For instance, the roots of Daesoon Jinrihoe can be traced back to Korean Shamanism, an ancient tradition predating Christianity. Historically, the decline of an old tradition can lead to the emergence of a new religion as an institutional or official model (Allport 1950). This article presents the argument that in the aftermath of the ancient religious system, Daesoon Jinrihoe took root and developed into a modern new religion. Therefore, while officially founded in 1969, Daesoon Jinrihoe's lineage intertwines with Korean shamanism and later influences from Chinese and Indian traditions such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. McGuire's analysis corroborates this narrative, demonstrating how many new religions, including Daesoon Jinrihoe, draw from Eastern spiritual traditions like Zen Buddhism, Hindu yoga, Sikhism, and Taoism.

However, most of the new religions often trace their origins to identifiable clusters of prior beliefs and practices as social phenomena. It is frequently observed that certain recurring factors contribute to the development of New Religions. H. Neill McFarland's (1960, 60) analysis, widely accepted, identifies at least five such factors: 1) social crises exacerbated by an invasive culture, 2) the presence of a charismatic leader, 3) the occurrence of apocalyptic signs and wonders, 4) expressions of ecstatic behavior, and 5) the adoption of syncretic doctrine. However, in addition to five factors, different categories of foundations in terms of the emergence of new religions in Korea are reported. Pokorny (2018) identifies twelve categories of foundations that have shaped the development of new religions on the Korean Peninsula since the 1860s. Turning our attention to Daesoon Jinrihoe and scrutinizing its major features and structure, we find it significantly influenced by these aforementioned factors in its development. Consequently, Daesoon Jinrihoe amalgamates essential elements of native Shamanism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Chinese lore. Others seek to interpret the emergence of new religions through various lenses, including social, cultural, economic, political, and psychological factors, which collectively create a spiritual vacuum within specific societies and situations. Most observers concur that the rise of new religions reflects a resurgence of old folk religious ethos (Alam 2020). Indeed, new religions, including Daesoon Jinrihoe, appear to offer a response to this vacuum, which may explain their dynamic nature.

Historically, new Korean religions emerged in the 19th century where Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism and Shamanism are found to be the bedrock of the new Korean religions. Although the nature of new Korean religions is shaped by conventional religions they emerged with a new and indigenous Korean unorthodox or nationalistic identity (Lee 2016). All new religions in Korea are syncretic in nature and are tightly connected to four traditional religions and typical Korean components. Historically, there is no dispute among the scholars of Korean NRMs in terms of the beginning of the emergence of new religious developments on the Korean peninsula in 1860 with the foundation of Donghak (Pokorny 2018). Il-Sup depicted a religious phenomenon of the emergence of new religions in Korea during and after the Korean War (1950-1953) that catalogs 170 movements (1985). Lee defines new religions in terms of integral parts of Eastern Learning (Donghak) as opposed to Western Learning (Seohak or Christianity). The four traditional religions had shaped the nature of the new Korean religions. In other words, for Lee, new Korean religions emerged in the 19th century, absorbed all existing religions, both orthodox and unorthodox, and integrated them into an ethnic Korean or nationalistic movement in character (Lee 2016). The purpose of the emergence of Donghak as a new religion was to make a religious stand against alien beliefs, especially Catholicism. This may also be considered as one of the major factors of emerging a counter movement or new religious movement. For Lee, (2016) the new Korean religions contain many unique Korean components or common heritages such as blood relations, regional ties, and historical senses of common destiny or collective community, with which they tried to ward off foreign invasion or threat by staging massive opposition movements for the Korean people who were in search of national freedom and glory, and thus it naturally contains more nationalistic components or connotations than otherwise. Byeonggil Jang defines new religion in terms of the popularity as found among the people in the lower classes of society who were poor and powerless in traditional Korean society. He continues that the religions before the 1930s in general should be called new religions, whereas those after the 1930s are called the newly risen religions which are regarded as distinctively different from the earlier ones (as cited in Lee 2016).

As far as the number of the followers of the new religions is concerned, between World Wars I and II, Korean new religions had more members than traditional religions (19th Population and Housing Census 2015). Although the numbers are undercounted in the government census, today, they still count their numbers in the millions. During and after the Korean War (1950-1953), new religions in Korea began to gain credibility, emerging as significant providers of social and educational services and presenting themselves as viable alternatives to traditional religions and mainline Christianity. This trend is exemplified by Daesoon Jinrihoe, which, without dispute among scholars of Korean new religions, stands out in the landscape of new religious movements due to its distinctive theological development, unique practices, and rapid growth within Korea. Historically, the reality is that all new religions were strongly opposed to Western encroachments in the middle of the 19th century. More specifically, most of the new religions on the peninsula had political ambitions. But the failure of Donghak Revolution in 1894 brought a change within the attitudes of Korean new religions. Indeed, in 1894, most of the movements shifted from political activism to social welfare and charity (Zoccatelli 2018).

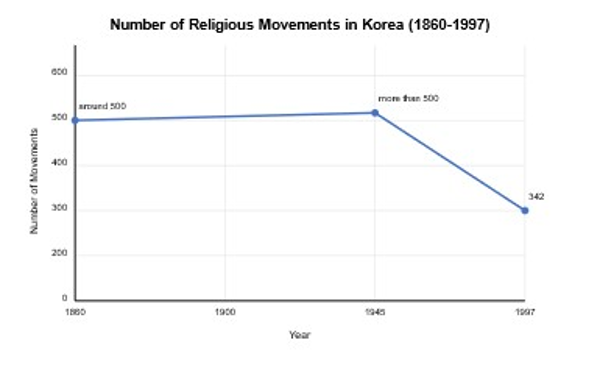

The number of movements that emerged on the Korean Peninsula since 1860 is presented here

Data Source: (Kim 2013; Ro 2008; Kim, Yu and Yang 1997 as cited in Pokorny 2018)

The graph illustrates the dynamic nature of religious and social movements on the Korean Peninsula over the specified period, with periods of growth, decline and stability.

The history of Korean NRMs, for Pokorny (2018, 236), is divided into five periods: 1860-the end of Joseon Dynasty 1910, 1910-1945 (the time of the Japanese colonial rule), 1945-1960 (the traumatic post-pacific war years exacerbated by the devastations of the Korean War 1950-1953), 1960-1980 (the era of accelerating industrialization and urbanization), and 1981-1987 (marked by increasing globalization, rapid technologizing). A timeline chart can be more suitable to focus on the situations that tremendously influenced Korean NRMs.

Each period is represented by a segment along the timeline. The significant situations of each period are mentioned below the timeline. The timeline stretches from the end of the Joseon Dynasty in 1860 to the year 1987. This visualization highlights the different situations that influenced the development of NRMs in Korea across the specified periods.

This bar graph presents the data as per the "2023 Religious Perception Survey (2023 Korea Research Regular Survey 'Public Opinion in Public Opinion')". According to Kim Taesoo, Research Professor of the Daesoon Academy of Sciences at Daejin University, the survey was conducted 22 times from January to November 2023. He claims that, according to the interviewee, in religious population surveys, members of new religious movements (NRMs) often either do not respond or, when they do, find that their specific religion is not listed among the options. Consequently, they frequently mark "no religion," resulting in only 2% being categorized as "other religions." While precise statistics are unavailable, Kim estimated that the actual number of adherents across all Jeungsan-based religious movements would not exceed 10 million. He further elaborated that, based on South Korea's 2023 population of 51.71 million, 20% would equate to 10,342,000 people. Thus, if the estimate of 10 million followers is correct, it would represent about 20% of the total population (Personal interview with Kim Taesoo, May 2024). However, this graph shows that:

The largest segment represents those who claim no religion, at 50%.

Christians make up 31% of the population, with Protestant comprising 20% and Catholic 11%.

Buddhists account for 17% of the population.

The remaining 2% is attributed to other religions such as ethnic or indigenous religions, new religious movements, Confucianism, Daoism, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Sikhism, Shintoism, and the Bahá'í Faith.

Notably, followers of Jeungsan-related Religions are less than 2%.

This graph approximately represents the revised data, with the non-religious category still being the largest group. However, as per the religious demographics, there is no leading religion in Korea. All religions are actively propagated. Although many countries of the world have one or more leading religions, Korea is considered a unique country where no religion takes the lead in socio-political or cultural aspects (Kang 2018). However, according to the South Korea National Statistical Office's 19th Population and Housing Census (2015), the number of non-religious people is increasing, while the number of people affiliated with other religions is dramatically falling.

With special reference to the Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements, Lukas Pokorny reported that South Korean academics are found to have adopted the term sinjonggyo (new religion) by the end of the 1960s. More specifically, sinjonggyo is included in the Great Encyclopedia of Korean National Culture (Han'guk minjok munhwa daebaekkwa sajeon) published in 1979. Since then, for Yi (2011 as cited in Pokorny 2018), Korean academia started to use the term sinjonggyo as the fixed designation for "new religion." Later on, sinheung jonggyo (newly-arisen religion) also appears to be synonymous with sinjonggyo.To go back in history now, the beginning of the academic study of 'new religions' in modern Korea laid its foundation in the 1930s. As Lee Gyungwon (2016) mentions Neunghwa Yi to have used the term 'new religion' (shin jonggyo) first in 1930 in his work, the History of Daoism in Korea. However, what is relevant to our understanding of Korean academia in terms of its attachment to 'new religions' there is no disagreement that the term 'new religion' began to be used in the late 1960s. Thus, the Association for History of Korean Religions in 1968, the Korean Association for Religious Studies in 1970, and Sin-Jonggyo-Yeongu (the Journal of t he Korean Academy of New Religions) are clear examples of the gradual development of Korean academia of 'new religions.'There is a widespread perception that since the early 1990s, scholars in Korea have studied it more objectively through research and creative discussion that significantly encouraged scholars from around the world in growing interest in the study of new religions on the Korean peninsula with great curiosity. This observation, thus, draws recognition that as a result of this trend of academic study of new religions in modern Korea, the term shinheung jonggyo (new religions) was at the height of its popularity in the early 1990s. In 1992, for example, Yi Kango is reported to have popularized the term new religions (shinheung jonggyo) in his monumental work, General Reports on the Newly Rising Korean Religions (Hanguk shinheung jonggyo chonggam) which includes all available new religions in Korea (Lee 2016).

From scholars' point of view, the academic study of Daesoon Thought is coeval with the establishment of Daejin University and the Daesoon Academy of Sciences in the year 1991 (Ko and Greenberger 2023). For scholars of Korean new religions, based on the researcher's direct observations during a brief field research in Korea from 2-13 April 2024, it is evident that Daesoon Jinrihoe holds significant importance both socio- historically and theologically, making it a focal point of research. For scholars of Korean new religions, as the researcher's direct observation both socio-historically and theologically, Daesoon Jinrihoe has long been a major focus of research. However, as George Chryssides (2022) aptly contends, the engagement of a new religion with the academic community, both within and beyond its country of origin, can prove to be an effective strategy for expanding its influence, as has been more recently demonstrated by the Daesoon Jinrihoe in collaboration with the Department of Daesoon Studies and the Daesoon Academy of Sciences.

Daesoon Jinrihoe is pronounced as "Daesoon-jill-lee-h'weigh," meaning "the Fellowship of Daesoon Truth". What is actually meant by the term "Daesoon Truth"? Although the Daesoon is translated as "widely touring the world" (Park 2016) the meaning of Daesoon is diverse, complex and comprehensive. In this regard, the Daoist concept of cosmic transformation, Buddhist ontological existential reality and Confucian social morality are also applied to the "widely touring the world" (daesoon). Park terms this threefold combination of Daesoon as the concept of trinity. Jin Y. Park (2016), "Truth and Spatial Imagination: Buddhist Thought and Daesoonjinrihoe," quoted Yang Moo Mock as providing a fivefold expression of the term Daesoon: 1) The Great Ultimate, 2) Exclusive Power of the Great Ultimate, 3) Mysterious Laws and Transformations of the Great Ultimate, 4) Process of Origin and Gradual Development of the Creation of the Great Ultimate, and 5) Equilibrium in Nature or Balance of Nature controlled by the Great Ultimate as Yang cited in Park (2016, 127) so. Park has summarized Yang's clarification and argued daesoon as an "exclusive power of the Lord on High (the Great Ultimate), the principle of the universe, and the foundation of all existence". Consequently, as Daesoon is assumed to be the foundational principle of everything, no individual existence can be separated from it. The metaphysical understanding of 'Daesoon' represents Sangje's Great Itineration of the world. In addition, for some scholars, the term 'Daesoon' is considered the 'Ultimate Truth' i.e., the Supreme God Sangje. To Chung (2016), for example, the term 'Daesoon' suggests the truth of all truths since it has examined all the truths in thorough and critical ways. Here in Chong's investigation, we find a sense in which none but only the Supreme Being can be the Truth of all truths. However, to search for the abstract notions of 'Daesoon,' Massimo Introvigne (2018) has identified that the term is used by Daesoon Jinrihoe with a plurality of meanings, including the cosmic movement of truth (jinri), which comes to permeate the world. What is the cosmic movement that permeates the world? It may be assumed that the 'cosmic movement' indicates the Exclusive Power of Great Ultimate that is all pervading.

However, by investigating diverse expressions of Daesoon, it seems highly probable that these expressions are tightly interconnected with each other centered on the Great Ultimate. To visualize the connection between the four attributes and The Great Ultimate, we can use a network diagram. In this case, the entities are the four attributes, and the c entral node represents The Great Ultimate.

In this network diagram, "The Great Ultimate" is at the center, and the four attributes are connected to it. The arrows indicate the connection between each attribute and The Great Ultimate. This representation visually shows how each attribute is connected to The Great Ultimate.

The background to the origin of Daesoon Jinrihoe can be understood from both narrow and broad perspectives. Broadly speaking, Daesoon Jinrihoe's roots extend to encompass all traditional Korean religions, including shamanism. On a more specific level, for Chryssides (2022), its lineage can be traced back to the Donghak movement (Eastern Learning). Is Daesoon Jinrihoe a minjung jonggyo (popular religion) or minsok jonggyo (folk religion) or minjokjeok jonggyo (ethnical religion) or jasaeng chonggyo (indigenous religion) or guksan jonggyo (native religion) or boguk jonggyo (nationalist religion), Hyeondae sinjonggyo (contemporary new religion), geundae sinjonggyo (modern new religion), sinsinjonggyo (new new religion)? As Daesoon Jinrihoe is distinctively a religion of Korean origin, its roots are tightly connected to both indigenous and native religio-cultural elements and traditional religions, especially of Chinese and Indian origins such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. As per the structure and characteristics of Daesoon Jinrihoe, it seems to be based upon shamanism (Musok) Buddhism (Bulgyo), Confucianism (Yugyo), Daoist (Dogyo) based.

Kang Jeungsan took national risk during the transition period of modern Korea. Japan invaded Korea and strengthened its position on the peninsula right after its victory over the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The colonial policy of imperial Japan was applied to the Korean Peninsula (Kim 2023).

Daesoon Jinrihoe, officially established in 1969, just ten years before the assassination of Park Chung Hee in 1979, claims to have represented the wisdom and spirit of Founder Kang Jeungsan's teachings. As per the new paradigm of new religions, the timeframe of the origination of Daesoon Jinrihoe falls into the category of both new and old religions. Scholars suggest using two key periods, World War II and the 1960s or 1970s, to determine whether a religion is still new or already old. Religions that originated after these periods are considered new. This particular religion is new in the sense that it was officially established in 1969, yet old because its formative period began with Jeungsan's religious movements and his opening of the great Dao of Heaven and Earth in 1901. However, it should be noted that this periodization is not mandatory for religions that emerged outside the Western world. Nonetheless, in the case of Korea, it is accurate to say that a new religious movement began with the emergence of Donghak in 1860 (Woo 2010).

Turning to the historical challenges of Daesoon Jinrihoe, we find that like almost all historical religions, its formation underwent many ups and downs. It should be mentioned, for example, that after the passing of Jeungsan in 1909, many small splinter groups appeared. For this situation of the growing organization, two major causes are marked such as the increasing Japanese control in Korea and the lack of leadership among followers of Jeungsan-related religions. However, the exact number of the splinter groups is not recorded. With regard to this issue there are two different versions. One study says about 60 groups with 10.2 million followers while the other suggests different figures such as 2.4, 4.8, or 7.2 million. Although we are not actually concerned with the interaction of these groups, each and every group is reported to have claimed to be the only legitimate followers of Jeungsan and his teachings (Chong 2016).

Moreover, regarding to the population issue again, Scholars, including Jeungsanists, acknowledge the difficulty to accurately account for the number of Jeungsan- worshipping devotees or calculate their percentage. To address this issue, several scholars of Jeungsan-related religions were interviewed. Their opinions are presented below:

Jason Paul Greenberger stated, “It would be rather difficult to find an accurate number.” For Greenberger(2024), the number of Daesoon Jinrihoe members registered by the Yeoju Headquarters Temple Complex was supposedly close to one million, spread across six different regions in Korea. Data from Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 2018 suggested that Daesoon Jinrihoe had around 1.63 million members, making it the fourth largest religion in Korea. Greenberger speculates that errors in other parts of the study led to its eventual retraction but believes the order of religions in the 2018 study feels accurate and is at least directionally correct. He explains that many surveys do not list Daesoon Jinrihoe or other Jeungsan-inspired NRMs as options. When they are listed, the results are quite impressive. An attempt to create an umbrella term, “Jeungsan-gyo,” failed as Daesoon Jinrihoe members identified themselves as “other” instead. He also notes that data on religious affiliations in Korea is often suspected of being inaccurate due to inflated membership numbers by various religions (Personal interview with Greenberger, May 2024 ). Kim Taesoo noted, “Many ordinary members of Daesoon Jinrihoe practice other religions simultaneously, making it difficult to determine the exact population. Based on estimates, the number of followers would be around 1.5 million,” though he acknowledges this is not a precise answer . Kim Taesoo noted, “Many ordinary members of Daesoon Jinrihoe practice other religions simultaneously, making it difficult to determine the exact population. Based on estimates, the number of followers (affiliated with the Yeoju headquarters temple) would be between 1.5 million and 2 million households,” though he acknowledges this is not a precise figure (Personal interview with Taesoo, May 2024).

Lee Gyungwon also mentions, “I cannot provide an exact answer because the percentage has never been calculated before, and there are significant differences between statistics prepared by the religious order versus those collected by the government.” He references a 1997 publication by Daesoon Jinrihoe Headquarters, which recorded 1,953,483 households as devotees, whereas the 2015 government census reported only 41,176 individuals. He notes that many scholars have criticized this discrepancy (Personal interview with Lee, May 2024).

However, estimates of the total number of devotees across all Jeungsan-related religions in Korea vary widely due in part to differing assumptions. Although a rough estimate of around six million is quite common, an influential source for this figure was a 1995 census report by the government census which forecasts that Jeungsanists numbers are a little over 6.2 million. At the same time, it also pointed out that as a proportion of followers of all religions in South Korea, the percentage of followers from Jeungsan-related religions will have fallen from less than 2% in (year) and the number would increase. It is important to note that this presumably undercounted study would still show Daesoon Jinrihoe to be the 6th largest religious community in Korea, behind only Buddhists, Protestant and Catholic Christians, Confucians and Won Buddhists Baker 2016.

Thus, the history of Jeungsan-related movements reached a matured stage when it produced a formidable new religious organization, Daesoon Jinrihoe, in South Korea in 1969. Moreover, there is also an important but often understated shamanistic legacy within the country’s religious landscape (Horak and Yang cited in Kim and Connolly 2021 ). More developments of the Jeungsan-related movements can be traced in this stage.

Daesoon Jinrihoe encompasses rudimentary, national, and universal forms of religion. From the perspective of religious classification, Daesoon Jinrihoe could be said to be both an organized form of religion and an official model of religion (McGuire 1997). Furthermore, it is a rudimentary form of religion because its roots can be traced back to the primitive religious systems of Korea. It is considered a national religion because, in line with the historical development of religion (Edwards 1965), Daesoon Jinrihoe shows no tendency to extend beyond its native boundaries through deliberate overseas propagation or missionary work. While Daesoon Jinrihoe may not be akin to Buddhism, Christianity, or Islam, it displays some tendencies toward becoming a universal religion. The central theme of a universal religion is missionary zeal, which includes propagation, proselytization, and expansion both within and beyond national boundaries, along with offering diverse social welfare activities. Although Daesoon Jinrihoe does not exhibit traditional missionary zeal, at least internationally, it is involved in various social engagements that suggest the "blossom of universalism" (Edwards 1965) within the religion.

A thorough study of some aspects of religious beliefs and rituals of Daesoon Jinrihoe consisting of symbolic actions suggest their links to the rudimentary form of religion. They are, for example, symbolic animal deities representing four seasons and four directions; twelve animal deities corresponding to the twelve months; the idea of twelve animals corresponding to twelve directions; twenty-four divinities overseeing the twenty- four seasonal subdivisions; the images of the twenty-eight divinities in charge of constellations etc. At this point, it should be mentioned that the characteristics of the rudimentary forms of religion or the primitive nature religions are found to be roughly similar everywhere (Hopfe 1983). This, according to the study of the Ministry of Culture and Information, Republic of Korea (1977, 150), is noted as "ingrained Korean habit of religious syncretism." However, the characteristics of these religious beliefs and rituals of Daesoon Jinrihoe are also not free of such "ingrained Korean habit of religious syncretism." In addition, as the rudimentary form of religion is based on animism or shamanism called mudang in Korean (Ministry of Culture and Information, Republic of Korea 1977), it refers to the direct involvement of Daesoon's roots with mudang as a persisting background.Moreover, as the traditional beliefs and religions of Chinese origin (or introduction) in Korea played a pivotal role as survivors of the most ancient religious system on the peninsula, it is assumed that almost all of the New Religions of modern Korea, with some exceptions, are tightly connected to Korean indigeneity (Ministry of Culture 1977). At this point, it makes clear that Daesoon Jinrihoe, as a syncretic religion, had its strong footing not only on the ancient religious system but also on Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism. According to Daesoon theology, the images of the twenty-eight divinities in charge of constellations represent the highest position of Sangje (the Supreme God), who reigns over the universe. The symbolic tower of these twenty-eight divinities in Daesoon resembles the Cao Dai concept of the roofless tower, the highest place where God reigns over the universe (Gobron 1950; Oliver 1976; Blagov 2001). In addition to animal deities and divine images, devotional offerings to mountain deities in Daesoon Jinrihoe correspond to the Shinto concept of kami. Elements of Daesoon Jinrihoe's beliefs and rituals appear more or less similar to various indigenous religious systems. This proposition actually demonstrates that Daesoon Jinrihoe holds a clear position as a polytheistic, panentheistic, and syncretic religion, while also encompassing aspects of complex monotheism.

The Deity or divinity in Daesoon Jinrihoe is a complex phenomenon when it is compared to the Abrahamic monotheisms such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, including Bahai Faith. According to McGuire (1997, 15), "The entire enterprise of theology out of which formal beliefs are developed represents a highly specialized and intellectualized approach to religion. But religion also includes less formal kinds of beliefs such as myths, images, norms, and values." If we consider McGuire's view and analyze it, our understanding suggests that although Daesoon's highly specialized and intellectualized approach is similar to that of Abrahamic traditions, there is a notable distinction. Specifically, the beliefs and practices of Daesoon Jinrihoe appear to be less formal compared to those in Abrahamic traditions.

God's communication through individuals is a concept acknowledged by nearly all religions worldwide. In A Lion Handbook: The World's Religions, R. Peirce Beaver (1982) delineated three primary conduits through which divine messages are conveyed: prophets, priests, and wise men. Among these groups, prophets often received direct communication from God, a phenomenon evident in both Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions. While God did not directly speak through priests and wise men, the former were tasked with imparting God's revelations, and the latter were entrusted with elucidating God's will. Christianity, while acknowledging the Old Testament as divine revelation, regards the New Testament as the ultimate expression of God's message. Notably, Daesoon Jinrihoe diverges from Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions in terms of its understanding of divine revelation. However, in Daesoon Jinrihoe, God Gucheon Sangje is believed to have descended to earth in the historical figure of Kang Jeungsan, akin to the Christian concept of God incarnating in the form of Jesus. In this light, it is crucial to note the parallels between the Christian notion of God's incarnation and the Daesoon understanding of Sangje's manifestation in Kang Jeungsan (Introvigne 2021). At this juncture, it is crucial to note that preceding Kang Jeungsan, Sangje communicated his messages through Choi Je-Wu (1824–1864). As one of the most prominent visionaries in Korea, he claimed to have a divine mandate as the basis for founding the Donghak religion in the late 19th century (Chryssides 2022).

It rather comes close to the pantheon of Shintoism, Hinduism, and Caodaism. The Chinese concept of the "God Gucheon Sangje" and "Jade Emperor", present within Daesoon theology, exemplifies Daesoon's assimilative and syncretic approach. This approach, as one of the fundamental principles of NRMs, seamlessly incorporates this idea from the ancient Chinese religious system without hesitation. The concept of Bahá'í and Sikh God differs from the concept of Daesoon Jinrihoe God. The concept of God in Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions is strictly monotheistic where no other entities are claimed to be gods or goddesses neither treated as part of the Supreme Being nor confess any partnership with the Supreme Being. The Hindu concept of the avatar appears in Daesoon theology, where Kang Jeungsan is referred to as the avatar of the Supreme God (Zhang and Greenberger 2023).It is argued that this concept is not directly borrowed from Hinduism rather from Mahayana Buddhism that developed and diffused throughout the length and breadth of China and later on the Korean peninsula and Japan.

The narrative with regard to Kang Jeungsan's position in Daesoon Jinrihoe pantheon presents him as a deity though available argumentation challenges this narrative and countered that rather followers respected him as the grand master (Daeseonsaeng) until 1919. But we can see later developments in terms of his position in the pantheon such as Daeseonsaeng is changed to Cheonsa (Celestial Master) while Cheonsa is finally changed to Gucheon Sangje (九天上帝, the Supreme God of the Ninth Heaven). This evolutionary development of Kang Jeungsan's position as a Supreme Being is confirmed on the basis of Kang's reconstruction work (Authority and Foreknowledge 1:9). Notably, Kang’s self-declaration as Supreme Being resembles the cry of the early Islamic mystic Hussain bin Mansur al-Hallaj, an’al-ḥaqq (Arabic: أنا ال َحقيقة, “I am the Truth,” one of the divine names of Allah) . Although there is a point of agreement between the two announcements, Hallajs announcement did not mean that he declared himself to be God but rather the truth. However, the orthodox misunderstood him to mean that he claimed to be God (Allah in Islam) and he was executed on charges of heresy. The sad story is that based on the ground of confusing justification he was killed on charges of heresy. Another similar story lies in the Upanishad Mahavakya: “Aham Brahmasmi” which means I am Brahman (the Ultimate Reality in Hinduism). With regard to “Aham Brahmasmi” and “Anal Haq” many like Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, a South Indian Sufi mystic, abandon the concept of “Aham Brahmasmi” and Anal Haq (Rahman, et.al. 2009).

In examining the aforementioned fivefold expression of Daesoon, especially the fifth one, we can see this equilibrium in close relation to the concept of Chinese harmonism, where humanity assumes an anthropocentric role bridging heaven and earth, aiming to restore balance to our world. Acknowledging our capacity to disrupt the natural order, humans bear the responsibility to cultivate a sense of unity and stewardship toward Mother Earth. Wang's insight resonates strongly in this context: "The whole world is regarded as a family. If we harm others, that means we harm ourselves."(Wang 2022, 42) His elucidation underscores the importance of harmony and collaboration over competition. It becomes evident that in the era of globalization and industrialization, lack of cooperation threatens human civilization with destruction, a reality we must confront.

Donald A. Westbrook (2023) applied Roy Wallis's typology of new religious movements—categorizing them as world-rejecting, world-affirming, or world- accommodating—to Daesoon Jinrihoe and preliminarily argued that the group appears to be both world-affirming and world-accommodating. This perspective aligns Daesoon Jinrihoe with religious traditions such as Judaism, Islam, the Bahá'í Faith, and Caodaism, which also do not necessarily reject the world. In contrast, this differentiates Daesoon Jinrihoe from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, which often promote priesthood, monkhood, and celibacy, thus encouraging a renunciation or rejection of worldly life and responsibilities.

Kang Jeungsan's methodology, when properly understood, emerges as both more peaceful and more fundamental compared to the leader of the Donghak movement. While the leader of Donghak exhibited political ambition, historical accounts reveal Jeungsan's adoption of a positive, constructive, and integrative approach, aimed at mitigating what describes as "massive deaths and fatal destructions"Kim (2016). Within Daesoon theology, Jeungsan is regarded as the incarnation of the Great Ultimate, a position akin to the Hindu concept of Lord Krishna, the eighth avatar of Lord Vishnu. Notably, in Hinduism, the exact date or year of Sri Krishna's incarnation is not definitively known. Introvigne (2018) proposes that in Daesoon Jinrihoe, the year 1871 marks the incarnation of Kang Jeungsan as God Sangje. However, in contrast to Lord Krishna, who possessed 16 divine qualities, including compassion, patience, forgiveness, and justice (Sugunan 2022),Jeungsan shared these divine attributes but did not approve of revolutionary action. While Krishna instructed Prince Arjuna to engage in a righteous war against evil forces, Jeungsan viewed revolutionary methods as inevitably leading to calamity for the people. In this aspect, Jeungsan's stance aligns with the teachings of Jesus, "Love your enemies" (Matthew 5:44, Luke 6:27). This nonviolent aspect of Jeungsan’s historical movement bears resemblance to Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance against British colonial rule in the early 1930s.

In summary, the classification of Daesoon Jinrihoe as either a new or established religion varies between scholars from the East and West. According to Western scholars, it can be claimed that Daesoon Jinrihoe is no longer a new religion, as its origins date back to Kang Jeungsan in 1901. Conversely, Oriental scholars, especially Korean who do not adhere to this standard, regard Daesoon Jinrihoe as a New Religious Movement. The socio-political conditions, timing, and needs of the Korean social milieu necessitated the emergence of Daesoon Jinrihoe, which aims to achieve human salvation by fostering a heavenly culture on earth, guided by God (Sangje). Daesoon Jinrihoe is a syncretic religion, incorporating persistent elements through the process of acculturation. As an organized and official model of religion, akin to Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Bahá'í Faith, Caodaism etc., Daesoon Jinrihoe is also seen to demonstrate how Jeungsan-related movements organize themselves to focus on shared meanings through four major aspects: religious belief, religious ritual, religious experience, and religious community (McGuire 1997).

Moreover, this article's clarification asserts that although Daesoon Jinrihoe is considered a New Religion, its roots trace back to the ancient religious systems of Korea, signifying its native or indigenous nature. As it has developed as a national religion, its social engagement projects demonstrate a tendency towards universalism, indicating its potential to evolve into a universal religion in the future.

A crucial theological element, according to Hill (1973), is the belief that priests and wise men are of little help, and that God can only be known directly by the chosen. This idea is reflected in the Daesoonist concept of the incarnation of Sangje (the Supreme God) as Kang Jeungsan, who claimed to be an incarnation of God and communicated directly with his disciples. This concept is similar to the Hindu Avatar Sri Krishna and the Cao Dai God Duc Cao Dai, who are also reported to have communicated directly with the chosen. However, a key difference is that no historical date is assigned to the incarnation of Sri Krishna, and the Cao Dai God never revealed Himself directly to the chosen.

Daesoon Jinrihoe stands as a multifaceted religion that blends rudimentary, national, and universal elements. Its deep-rooted connections to Korea's primitive religious systems, coupled with influences from Daoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and folk religion, highlight its syncretic nature. The religion's rich tapestry of beliefs and rituals along with its theology centered on Sangje, positions Daesoon Jinrihoe as a polytheistic, panentheistic, and syncretic religion with complex pseudo-monotheistic aspects. Despite its native and national focus, the religion's social engagements suggest a potential for broader universal relevance. However, while Daesoon Jinrihoe does not offer a grand theory of universalism, its position aligns with the universal tenets found in religions like Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as later movements such as the Bahá'í Faith and Caodaism.

Ahmed, Ishtiaq. 2009. "Politicized Religion: The Cases of India and Pakistan." South Asian Review 30(1): 65-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.2009.11932659

Chryssides, George D. 2022. "Disseminating Daesoon Thought: A Comparative Analysis." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 1(2): 13-39. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2022.1.2.13

Daesoon Institute for Religion and Culture (DIRC). 2020a. The Canonical Scripture. Yeoju: Daesoon Jinrihoe Press. http://dict.dirc.kr/app/e/1/page

Daesoon Institute for Religion and Culture (DIRC). 2020b. The Guiding Compass of Daesoon. Yeoju: Daesoon Jinrihoe Press. http://dict.dirc.kr/app/e/2/page

Daesoon Institute for Religion and Culture (DIRC). 2020c. Essentials of Daesoon Jinrihoe. Yeoju: Daesoon Jinrihoe Press. http://dict.dirc.kr/app/e/3/page

Hartney, Christopher. 2022. "Vietnamese Syncretism and the Characteristics of Caodaism's Chief Deity: Problematising Đức Cao Đài as a 'monotheistic' god within an East Asian Heavenly Milieu." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 1(2): 41-59. https://doi.org/10.26338/tjoc.2018.2.5.4

Introvigne, Massimo. 2018. "Daesoon Jinrihoe: An Introduction." The Journal of CESNUR 2(5): 26-48. https://doi.org/10.26338/tjoc.2018.2.5.4

Introvigne, Massimo. 2021. "Jo Jeongsan in Context." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 1(1): 17-37. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2021.1.1.17

Jin, Jung Ae. 2011. "A Review on the Object of Belief of Bocheon-gyo and Mugeuk-do." Journal of New Religions 25(0): 167-197. [Korean Language Text] 「보천교와 무극도의 신앙대상에 대한 고찰」,『신종교연구』. https://doi.org/10.22245/jkanr.2011.25.25.167

Kang, Donku. 2018. "Cultural Identity and New Religions in Korea." The Journal of CESNUR 2(5): 8-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020066

Kim, Andrew Eungi and Daniel Connolly. 2021. "Building the Nation: The Success and Crisis of Korean Civil Religion." Religions 12(2): 66. http://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2023.3.1.57

Kim, David W. 2023. "The Post-Jeungsan Grassroots Movements: Charismatic Leadership in Bocheongyo and Mugeukdo in Colonial Korea." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 3(1): 57-85. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2023.3.1.33

Kim, Hiheon. 2016. "Hoo-Cheon-Gae-Byeok as a Korean Idea of Eschaton: A Comparative Study of Eschatology between Christianity and Dae-Soon Thought." In Daesoon Jinrihoe: A New Religion Emerging from Traditional East Asian Philosophy, edited by the Daesoon Academy of Sciences, 17-58. Yeoju: Daesoon Jinrihoe Press.

Ko, Namsik and Jason Greenberger. 2023. "A Study on the Relationship between Kang Jeungsan and Jo Jeongsan Described in Chapter Two of Progress of the Order." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 3(1): 33-56. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2023.3.1.33

McFarland, H. Neill. 1960. "The New Religions of Japan." Contemporary Religions in Japan 1(3): 30-39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i30232813

Pokorny, Lukas, eds. 2018. "Korean New Religious Movements: An Introduction." In Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements, edited by Lukas Porkony and Franz Winter, 231-254. Leiden and Boston: Brill. https://www.academia.edu/39945453/2018_Korean_New_Religious_Movements_An_Introduction

Shim, Il‐Sup. 1985. "The New Religious Movements in the Korean Church." International Review of Mission 74(293): 103-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-6631.1985.tb03323.x

South Korea National Statistical Office. 2015. 19th Population and Housing Census. Retrieved May 18 2024. https://En.Wikipedia.Org/Wiki/Religion_in_South_Korea#Cite_.Office,South Korea National Statistical

Sugunan, Sreejith. 2022. "The Bhagavad Gita and the Ethics of War." Religion and Humanitarian Principles. https://blogs.icrc.org/religion-humanitarianprinciples/bhagavad-gita-ethics-war/

Wang, Zhihe. 2022. "Haewon-sangsaeng, Chinese Harmonism and Ecological Civilization." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 2(1): 31-56. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2022.2.1.31

Westbrook, Donald A. 2023. "Freedom of Religion, Sangsaeng, and Symbiosis in the Post-Covid Study of (New) Religions." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 2(2): 51-72. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2023.2.2.51

Zhang, Rongkun and Jason Greenberger. 2023. "Fasting of the Mind and Quieting of the Mind: A Comparative Analysis of Apophatic Tendencies in Zhuangzi and Cataphatic Tendencies in Daesoon Thought." Journal of Daesoon Thought and the Religions of East Asia 2(2): 33-50. https://doi.org/10.25050/JDTREA.2023.2.2.33

Zoccatelli, PierLuigi. 2018. "Introduction: The Korean 'Rush Hour of the Gods' and Daesoon Jinrihoe." The Journal of CESNUR 2(5): 4-7. https://doi.org/10.26338/tjoc.2018.2.5.1