1. INTRODUCTION

Social media has become a medium for information sources on important issues such as health, parenting, political issues, and other important information that affects individuals and society. It influences one’s behavior (Tham et al., 2020), opinions, and attitudes, particularly among the youth (Ida et al., 2020; Karamat & Farooq, 2016). In particular, young adults favor social media as a source of news (Nazari et al., 2022). While it has become a source of useful information, it is also considered a source of what is commonly referred to as “fake news.” The rise of users and the continuing sharing of information on the platform is also proportional to the number of incorrect or manipulated content sources on the platform (Thurman, 2018). Sources of this content come from independent sources, individuals, or partisan-supported accounts, which raise the issue of biases in mainstream media. This may contribute to the tendency of social media users (SMUs) to share news from independent, non-mainstream sources rather than the mainstream press (Nekmat, 2020).

Misinformation and disinformation are two closely-related concepts popularly linked to “fake news” in social media. The former pertains to inaccurate information distributed unintentionally or without manipulative intent, while the latter is focused on “information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country” (Moscadelli et al., 2020). Other related terms include alternative facts, misinformation, media manipulation, and propaganda (Jahng, 2021). The spread of this type of information uses social networks or messaging services. With the limited regulation within this type of online environment, monitoring and control rely only upon its users. New emerging and unfamiliar SMUs tend to fall victim to this fake news. For example, a recent study on social media shows that older adults tend to share fake news articles to a greater extent compared to younger age groups (Guess et al., 2019).

One of the actions taken to address the spread of “fake news” in social media is to utilize fact-checking services. Fact-checking service is “the practice of systematically publishing assessments of the validity of claims made by public officials and institutions with an explicit attempt to identify whether a claim is factual” (Walter et al., 2020). For example, BBC Reality Check has been looking at some of the claims made during the debate about the 2019 UK election. These programs are of interest to the public domain because they provide analyses and assessments of information spreading on social media platforms. It has also been adopted by mainstream media as part of reporting, such as the New York Times, and has been recognized through journalism awards (Graves, 2013). However, recent fact-checking services include content beyond political issues, such as health-related occurrences during the pandemic (Ceron et al., 2021), to name a few.

Against this backdrop, this study intends to determine two aspects that affect SMU and fake news. First, it identifies how SMUs verify the information they encounter on social media. Secondly, it determines the perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and perceived trust in fact-checking services. The first objective intends to understand the practices of information verification, while the other aims to understand fact-checking services from the SMU perspective. Knowing information verification practices and the perception of SMU will support the purpose of having fact-checking services as a response to fake news propagation. Having data about the perception of users can also provide insights into the effectiveness of fact-checking services. We posit that the public must be able to appreciate and have a positive attitude toward fact-checking services to be able to fully rely on them.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

While studies on fact-checking services have been found to influence the perception of individuals, their effectiveness in addressing the proliferation of “fake news” has mixed results. Nonetheless, indicators of effectiveness have been identified, including format and tone (Young et al., 2018), warnings and tags (Clayton et al., 2020), and the use of messages such as graphical elements (Walter et al., 2020). These fact-checking graphical elements resulted in an unexpected result. For example, integrating visuals into fact-checking messages tended to be less effective than those that did not integrate them (Walter et al., 2020). These studies provide evidence that the presentation of information lacked the element for SMUs to assert the truthfulness of the information they have seen in social media feeds.

Integrating indicators in social media shapes individual views. Rhodes (2022) shows how social media conditions are less critical of information as an effect of filter bubbles and echo chambers. While the integration of warnings or flags in social media decreases belief in the accuracy of headline news, the need to fight fake news proliferation persists (Clayton et al., 2020). Various recommendations for further studies were also mentioned, including an exploration of fact-checking services and social media. For instance, Chung and Kim (2021) suggested that measuring how participants perceive fact-checkers would provide a better understanding of fact-checking information.

Extant literature about fact-checking has shown inconsistent results regarding its benefits or effectiveness to users. An experiment about the credibility of perception regarding fact-checking labels on news memes showed that fact-checking labels do not seem beneficial to the credibility of the perception (Oeldorf-Hirsch et al., 2020). On the other hand, to reduce belief in misinformation and false stories on Facebook, strategies on tagging were deployed. It was found that “Rated False” tags are more effective than “Disputed Tags” (Clayton et al., 2020).

External fact-checking organizations were also considered effective in addressing misinformation. Amazeen et al. (2018) concluded that “those who saw a correction were significantly more accurate in their assessment of the controversial statement than those who did not see a correction.” Nyhan and Reifler (2015) argued that those participants who were shown fact-checks were able to correctly identify factual information. Similarly, in an experiment on warning labels for false news, it was also concluded that they were effective in reducing the tendency for users to share the said news (Mena, 2020).

A flurry of recent research has centered on recognizing and minimizing the danger of fake news stories spreading to social media sites. The work of Babaei et al. (2021) focuses on how users perceive truth in viral news stories. The researchers conducted online user surveys asking people to rapidly assess the likelihood of news stories being true or false, and to quantify to what extent users can recognize (perceive) a news story’s accurate truth level obtained from fact-checking sites like Snopes and Politifact. In 2018, an article by Cunha et al. (2018) quantitatively analyzed how the term “fake news” is being shaped in the news media. The article provides a closer look at how the word “fake news” is influenced by newspapers and magazines around the world – a relevant social trend linked to disinformation and deception and encouraged by the rise of the Internet and online social media. The researchers studied this expression’s interpretation and conceptualization through quantitative analysis of a broad corpus of news reported in 20 countries between 2010 and 2018, and supplemented the research with data collected from online search queries that help determine how public interest in the term “fake news” has evolved in different places over time and the ideas around it. These findings extend the definition of the use of the term “fake news” to help understand and describe this relevant social trend correlated with disinformation and deception more accurately.

While services for fact-checking and verification in social media have increased to counter fake news, little research has investigated how SMUs perceive the programs as a means to address the proliferation of misinformation (Brandtzaeg et al., 2018). The findings suggest that while young journalists are largely unfamiliar with or ambivalent about such services, they consider them potentially useful in the journalistic investigative process. A contrast between the opinions of journalists with those of SMUs indicates equally ambivalent SMUs. Several highlighted the value of such services, while others conveyed intense mistrust. The journalists, however, showed a more nuanced perspective, both finding such services to be potentially useful and hesitant to blindly trust one service. The researchers suggested development techniques to make online fact-checking services more efficient and accurate.

Despite the effort of fact-checking organizations, public trustworthiness with fact-checking sites, including Snopes, FactCheck.org, and StopFake, was still negative (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017). Moreover, a discussion about a post on fact-checking services showed that readers have mixed reactions and are considered skeptical of fact-checks. However, interviews with journalists showed a more positive orientation toward learning information about misinformation (Brandtzaeg et al., 2018). The challenge is that human fact-checkers are said to have difficulty keeping up with the amount of misinformation and the pace at which it spreads. This challenge gives automated fact-checking systems an incentive. On the other hand, fact-checking technology is falling behind because there is no current program that does automated fact-checking. Today’s professional fact-checkers conduct their research tirelessly as an art, following good data practices and investigative journalism (Manolescu, 2017).

3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

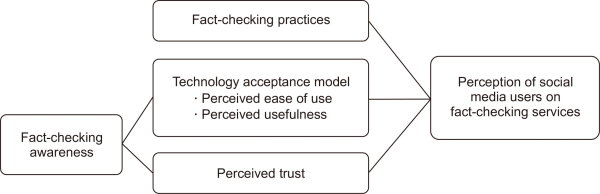

The concepts adopted in this study were anchored on the technology acceptance model of Davis (1989) and perceived trust by Roca et al. (2009). In addition, fact-checking practices of SMUs were analyzed as supporting data about their perception of fact-checking services.

Fig. 1 shows the conceptual framework of the study, which illustrates the concepts used to determine the general perception of SMUs on fact-checking services. The first approach deals with determining how SMUs verify the information they encounter on social media platforms. The practices were derived from emergent themes from the interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) of SMUs. The second approach adopted the concept of Davis (1989) on the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of fact-checking services’ social media posts and their corresponding websites. Moreover, perceived trust is a concept that determines how trustworthy the fact-checking services are from the perspective of the SMU. We adopted the concept of Roca et al. (2009) that defined trust as a concept “based on the rational appraisal of an individual’s ability and integrity, and on feelings of concern and benevolence.”

As perceived by SMU, ease of use is a technology acceptance construct that pertains to the simplicity of navigating, exploring, and getting information from websites or social media posts. It is about how easily the system facilitated arriving at a goal or task. According to the technology acceptance model of Davis (1989), perceived ease of use leads to the perceived usefulness of the artifact. Perceived usefulness is defined by Davis (1989) as the “degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance.” Given these constructs, it can be interpreted that the more agreeable the SMUs are in terms of the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, the greater chance that they will use the fact-checking services. This idea will support the adoption of SMU in fact-checking services.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1. Context of the Study

In the Philippines, social media is an influential platform with an average daily usage of 4 hours and 12 minutes (Gonzales, 2019). The country is also considered one of the top SMUs worldwide, comprising more than 73 million users in early 2020 (Kemp, 2020), or around 68% of the country’s total population. These users produce and share content in their timelines which include news and current affairs information circulating on the platform. Due to this massive usage of social media, unfortunately, the country faces an active spread of misinformation, disinformation, and related phenomenon in social media as a production network to promote political-related information (Ong & Cabañes, 2018). In a way, social media has become a source or a platform for news and even for political engagement (David et al., 2019), which other people would think is the reason why the platform has been viewed as influencing political matters (Zhuravskaya et al., 2019). Another important thing to note is that during the COVID-19 outbreak, it was observed that vaccine hesitancy was highly influenced by fake news based on previous vaccine cases in the country (Yu et al., 2021).

Among other media organizations in the Philippines, Rappler and VeraFiles were tasked by Facebook as third-party fact-checkers (Magsambol, 2018). Rappler is an online news organization that has been accessible online since 2012. According to its website, it “is composed of veteran journalists trained in broadcast, print, and web disciplines working with young, idealistic digital natives eager to report and find solutions to problems.” VeraFiles, on the other hand, is a non-stock, non-profit organization founded in 2008. As stated on its website, it is “published by veteran Filipino journalists taking a deeper look into current Philippine issues.” Compared to the majority of the news agencies in the country, these two media organizations are relatively new.

4.2. Data Collection

A FGD was initially conducted to identify information verification practices as well as to solicit from the FGD respondents their level of awareness towards available fact-checking services in the Philippines. To recruit such respondents, purposive sampling was employed. An announcement was initially posted in several conspicuous areas around the university inviting active SMUs interested in participating in the research on fact-checking. Out of those who responded, the researchers then purposely selected and grouped them into five or six groups based on varied criteria. It is important to note that not all of those who responded to the initial invitation were able to show up within the scheduled time set by the researchers. Such a phase gathered a total of 121 respondents. Table 1 shows the profile of the FGDs conducted.

Table 1

Focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted

| Number of participants | Average age | Date | Method of data collection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGD1- University students | 5 | 19 | February 20, 2020 | Face to face |

| FGD2- Students and young professionals | 5 | 25 | March 30, 2020 | Online FGD (via Messenger) |

| FGD3- Young professionals | 4 | 30 | April 15, 2020 | Facebook Messenger Chat Group |

| FGD4- Mixed participants | 4 | 23 | April 27, 2020 | Online FGD (via Messenger) |

| FGD5- Working professionals | 4 | 28 | May 10, 2020 | Online FGD |

| FGD6- Working professionals | 4 | 37 | Nov to Dec 2020 | Facebook (via Messenger) |

Based on the list of respondents, individual interviews were then conducted either through face-to-face, online chat, or personal voice call methods. While the FGD was used to capture the shared experiences of SMUs, the individual interviews were intended to capture and confirm individual cases that might not be shared in a FGD. In a way, this method was used to avoid the feeling of embarrassment among the participants, who may be accused of being a sharer of fake information. Table 2 shows the summary of the profile of the participants.

Table 2

General profile of the participants for individual interviews

| Participant | Age | Gender | Educational attainment | Social media usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 55 | M | Vocational school | Seldom |

| P2 | 45 | M | Bachelor’s degree | Always |

| P3 | 40 | F | Doctorate | Always |

| P4 | 22 | F | College level | Frequent |

| P5 | 22 | M | College degree | Always |

| P6 | 20 | M | College level | Always |

| P7 | 20 | F | College level | Always |

| P8 | 19 | F | College level | Always |

| P9 | 35 | F | College graduate | Always |

| P10 | 22 | M | College graduate | Always |

| P11 | 24 | F | College graduate | Always |

| P12 | 21 | M | College graduate | Always |

| P13 | 25 | F | College graduate | Always |

| P14 | 23 | M | College graduate | Always |

| P15 | 19 | G | College level | Always |

| P16 | 31 | M | College degree | Always |

| P17 | 23 | G | College degree | Always |

The guiding research questions during the conduct of the individual interviews as well as the FGDs were as follows:

-

How do SMUs verify the information posted on social media?

-

How was their experience in using the fact-checking platform?

The first question was used to facilitate how a SMU verifies the context of the post shown on their timeline. It also intends to capture the process and their experiences in using the platform. The second question intends to solicit qualitative data to support or contradict the user experiences regarding ease of use, perceived usefulness, and perceived trust in fact-checking services. Box 1 shows the guide questions during the interviews.

Box 1

Can you share your opinion and experience in using social media page as a source of information? (How often, when to share, tagging)

How did you determine if the information posted on social media is true or reliable? (use of fact check and other sources, use of search, determinants of fake news, sources of reliable info)

How was your experience in using the fact-checking platform? (ease of use, usefulness, biases)

How did fact-checking services (Rappler/Vera Files) help you?

Can you share a memorable experience about the fact-checking experience?

What do you think are the reasons why people share unreliable news?

What do you like most about fact-checking? (don’t like, interesting or not)

Can you suggest anything on how to improve fact-checking?

Anything you want to share.

Although the intention was to record all interviews through a voice recorder, during the actual interview some participants refused the recording due to personal reasons. To address this, field notes were utilized to capture important information shared by the participants. Field notes were handwritten notes to capture the thoughts or important phrases shared by the participants.

For the survey, the study employed convenience sampling. While it was the intention to share and distribute the survey instruments in groups or among students in different schools through personal relations or connections of the researchers in the various regions, when the pandemic hit and eventually affected the way the research was initially conducted, the team opted for convenience sampling, as it was challenging to personally visit the contacts due to travel restrictions and the strict health and community quarantine protocols being implemented. The survey adopted a modified questionnaire by Davis (1989) by changing the items (i.e., CHART-MASTER) of the system into “fact-checking services.” Moreover, a five-point Likert scale was likewise adopted instead of the original one to simplify the perception of SMUs. For example, for the Usefulness scale, the options include Agree, Slightly Agree, Neutral, Somewhat Disagree, and Disagree.

A total of 685 responses were gathered from the Google Forms distributed through referrals. The initial survey was conducted in Iligan City, Philippines to test the possible responses of the participants. The survey was then revised to eliminate confusing questions and add additional options on news sources shared on social media.

The questionnaire measured the perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and trust in the platform. The data gathering was conducted from February 2020 to November 2020. Considering the strategy of deploying Google Forms as a survey instrument, the study makes no claims that the data is representative of the broader population in terms of SMUs in Mindanao, the southern island of the Philippines. However, although the sample may not represent the broader population, the perception of the users does not necessarily negate the result of the survey.

It should be pointed out that the respondents participated voluntarily in the study. It was as well made clear to the participants that they have the right at any stage to withdraw from the study if needed. Google Forms also contained a voluntary consent tab that the participant must check before proceeding to the survey questionnaire to ensure informed consent. Suffice it to say, this research complied with the University Human Research Ethics Review Process.

4.3. Analysis of Data

For qualitative data from FGDs or individual interviews, the researchers used the thematic analysis method for analyzing the data. The researchers closely studied the data to identify common themes (topics, concepts, and sense trends) that repeatedly came up. Thematic analysis is a good approach to research for finding out something about the beliefs, thoughts, expertise, perceptions, or values of people from a collection of qualitative data, interview transcripts, social media profiles, or survey responses (Caulfield, 2019). The primary purpose of the interview and focus group were to determine the process or ways the participants could verify the data posted on social media sites.

For the survey data, a total of 685 respondents participated in the survey. The average age of respondents was 22 years old. Around 46% (318) were males while 364 were female. Four of the respondents preferred not to say about their gender.

For the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and trust, the researchers rehashed the 5-point scale into 3, where slightly agree to agree was grouped and converted as agree, and the same applies to the disagree scale. This scale simplified the number of participants who tended to slightly agree or to agree into one group. However, the average was still computed based on the answers.

5. FACT-CHECKING PRACTICES AND PERCEIVED ACCEPTANCE

Derived from the themes that emerged from the data, SMUs showed several practices that may have implications on how they ensure the veracity of information encountered on social media platforms. It is also important to note that, in general, the characteristics of users in how they describe themselves as active SMUs reflects their fact-checking practices.

5.1. Cross-Checking with Other Sources

Active SMUs who are aware of the widespread fake news on social media tend to cross-check for other references. Cross-checking with other sources is the process of verification where a SMU accesses other relevant references to confirm the factuality of the information on a social media platform. This is usually done using a search engine (e.g., Google) to check for related sources or if someone has pointed it out as fake news or misinformation. For instance, FGD2.2 said, “I now use Google Scholar and other authorized and trusted websites.” By checking with other sources, SMUs can confirm if the information encountered in social media is accurate.

5.2. Verifying Source and Account Credibility

Account verification and account credibility pertain to accounts recognized by their organization or individual as their official social media page. The Department of Health’s official account for health-related information, especially during COVID-19, is considered a credible and verified source. When validating a certain post, some users trace the source of the account. When certain posts catch SMUs’ interest, they also tend to check the credibility of the source or account. This is done by checking the source, profile, and previous posts of the account. For example, when news about a death of a known or famous person pops up the tendency is to immediately check who shared it. A participant supports this idea: “and yes also considering the source of the posting. But, more of Twitter as source” (FGD2.3). In the perception of the user, before the mainstream media posts breaking news, someone will share it on Twitter or Facebook.

Most SMUs are also aware of the spread of misinformation on social media platforms. It was shared by one of the participants in one of the FGDs.

I really think that amidst this pandemic, people should be more cautious in sharing and believing to posts in any form of media. We should be very keen on details including double-checking the account source.

(FGD2.3)

There are also cases where a SMU considers mainstream media as a verified source. Even if particular news has been shared by an ordinary user but the source of the shared information is credible, it can be considered to be verified by the user.

If the shared news is also coming from a mainstream media, I consider it as a credible source of information, so verifying it with other users may not be needed since I considered it verified considering the source information.

(P8)

Indeed, checking the source of information is one recommended practice in addressing misinformation or fake news on social media. As Osatuyi (2013) explained, information credibility is operationalized by the ability of the user to verify or confirm based on the cues encountered on social media sites.

5.3. Inspecting Comments and Reactions

Those who lack awareness are influenced by the opinions they encounter in social media posts by other users, especially those they are following (Akdevelioglu & Kara, 2020), or by the common news feeds in the users’ accounts. One process that has emerged as one of the verification practices is checking for comments and reactions to the posted information. Sometimes by reading comments on the post, issues related to the post can also be confirmed if there is associated misinformation. For instance, Participant 4 of FGD 7 shared, “But my usual first action is to read comments. Conflicting views trigger me to verify it on other sites if it hits my interest.” This answer indicates that comments under a particular post may trigger the verification process.

One of the first actions taken after reading a particular post is reading comments and reactions to the post, which matters to the user.

For me, I will look at the comments to see if there are people who contradict the posts, and then I will search for the truth myself to determine if it’s true or not and also if I can gain knowledge.

(FGD3.2)

But my usual first action is to read comments. Conflicting views trigger me to verify it on other sites if it hits my interest. Also, I look at who shared the news if I don’t know the person. Sometimes my acceptance of the content is based on the person or author who shared it.

(FGD 7.4)

Reactions to a post also may suggest something else.

5.4. Confirming from Personal and Social Networks

Validating information through personal circles also emerges as one of the practices among active SMUs. This pertains to asking about the factuality of the information encountered in social media from families and social media networks. Under this theme, there are three major ways to validate the information.

First, a SMU asks directly to people around when the information is encountered. P12 confirms that sometimes it is easier to directly ask the person around you when you encounter interesting information shared on social media, as he said, “I can easily show it to them,” referring to the information he wants to clarify, demonstrating by holding his phone. Indeed, it is easy to allow people to confirm, hoping that they have encountered similar information before. Moreover, P1 and P2 have already established their trust in family members or close relatives, as they both said, “I tend to share and believe information if it comes from a relative.” This is another way of confirming information from the inner circles of an active SMU. They also tend to easily believe since these are people they tend to trust.

If people are not around, sharing to a group chat is another strategy for verifying posts among active SMUs. With the presence of private group chats, they become an avenue to share and verify information encountered on the platform. For example, P12 said “Because close connections see group chats, I tend to share the information I encountered with them and ask if the information I have seen is real or fake.” The belief is that a limited audience or group can confirm the information easily when none is physically present when the content is encountered.

Lastly, the riskier move is to share the post to get feedback from other SMUs. For instance, “I just always share and share other posts, and I don’t think if it’s fake or truth” (FGD2.2). They are the type of user who has minimal knowledge about misinformation circulating on social media websites or those who are lackadaisical about it. Take, for example, P1: “I shared so that I will know if it is also true.” This unconcerned SMU tends to propagate the post without critically evaluating the post as to whether it is factual or not. In the latter part of the conversation, this experience also taught a lesson to P1.

During my college days, I really didn’t care or think about what will happen next, I just shared some sort of information that I got, and after the day, I was shocked because it reached Cagayan de Oro and other places. I did cry because the sharer of the information told me that she was angry about it. .

5.5. Awareness of Respondents to Fact-Checking Services

Awareness pertains to the exposure of an individual to an advertisement or persuasive message about a certain product or service (Lavidge & Steiner, 1961). Fact-checking services pertain to the consciousness of the individual who either hears or encounters a post or information on a social media platform. In the survey, out of the 685 respondents, 424 (62%) answered “Yes” to the question, “Are you aware of Rappler and Vera Files as fact-checking programs of Facebook?” However, when asked if they had experienced using the services, only 316 confirmed that they had. That means only 46% of 685 (or 351) have experience using it. Moreover, specific to Rappler and Vera Files as recognized fact-checking programs, only 22% (153) answered “Yes” when asked the question, “Have you used Rappler or Vera Files to check for facts?”

5.6. Perceived Ease of Use, Usefulness, and Trust in Fact-Checking Services

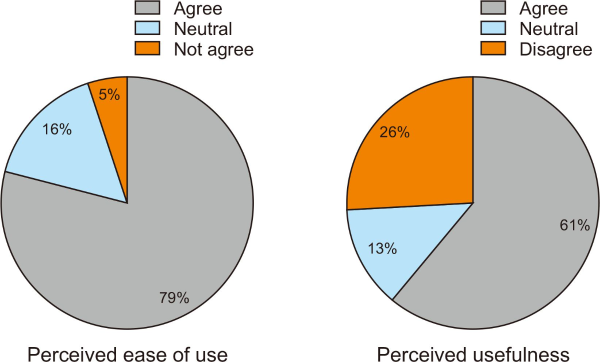

Out of 316 participants who confirmed their experience using a fact-checking service, 79% (250) agreed that it was easy to use, while 5% (16) did not agree. On a 5-point Likert scale, the mean is 4.06, which can be interpreted as “Agree.” This can generally be interpreted as easy to use.

For perceived usefulness, 193 (61%) individuals considered fact-checking services as useful while only 26% disagreed. The average rating is 3.62, which is relatively lower than the average score for perceived ease of use. This result confirms that most SMUs considered fact-checking programs they encountered on social media as useful despite issues of fact-checking in the extant literature (e.g., Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017).

Fig. 2 shows the comparison of perceived ease of use (A) and perceived usefulness (B) in terms of percentages. It can be seen that many disagreed on perceived usefulness compared to perceived ease of use of fact-checking services.

SMUs perceived fact-checking services as useful in their presentation of information, particularly labeling images or statements shared on social media. This presents the usefulness of fact-checking services. However, other users commented that the search support or confirmation is limited for the information they encountered in fact-checking posts. In other words, the information the users need is not available on the fact-checking platform. The need to be responsive to information that must be verified in social media cannot cope with the fact-check services’ capacity to respond.

The role of trust in fact-checking is critical because it is the basis for which SMUs rely on what they have read, especially relating to political matters. To determine the trust level of SMUs to fact-check services they encountered on social media or websites, we asked them to rate their perceived trust in different mainstream media fact-check entries.

Varied responses were received for the different fact-checking services. In the pilot survey, only Rappler and VeraFiles were included. However, in the comment section, there were suggestions to include other mainstream media because they also include fact-checking services on their respective websites. Thus, we decided to include others as suggested by the respondents. For Rappler, 40% take a neutral stance, while 27% have trust and 33% choose not to trust. VeraFiles got 61% neutral and 25% on trust, and 14% distrust.

In summary, SMUs were ambivalent about the various fact-checking programs they encountered on social media, as shown in Table 3. With most users taking a neutral stance on the fact-checking service except for CNN Philippines Fact-Check, it follows that the fact checking services could not capture an important purpose of a fact-checking service. With the recognized fact-checking services by prominent social media platforms, more than 50% of the respondents were neutral or answered that they were untrustful of recognized fact-checkers (Rappler and VeraFiles). This is because some participants believed these fact-checkers were one-sided or favored one political party. Similarly, the Pew Research Report on Americans polls about the usefulness and trustworthiness of fact-checking services yields the same perception. The report states that almost half of the participants “tend to favor one side” (Mitchell et al., 2019). This calls for a need to build an unbiased reputation for fact-checkers to improve usefulness and trust with social media participants.

Table 3

Summary of the perceived trust to fact-checking services

| Fact-check/Media organization | Trust | Neutral | Distrust | No. of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fact Check Philippines | 40% | 52% | 7% | 459 |

| Rappler Fact Check | 27% | 40% | 33% | 469 |

| Vera Files Fact Check | 25% | 61% | 14% | 360 |

| CNN Philippines | 69% | 28% | 3% | 424 |

6. DISCUSSION

The information verification practices derived as themes showed the behavior of SMUs when vital information is encountered on social media platforms. Cross-checking and source credibility are practices that can also be observed among journalists, especially for distant sources (Wintterlin, 2020), to verify the information they acquired. This confirms that such a practice can be considered a good exercise for SMUs. On the other hand, inspecting comments and reactions may indicate the need for information literacy among SMUs. The practice of referring to comments may contribute to how misinformation spreads on the platform.

Although good information verification practices are common to journalists and SMU, some practices might contribute to the proliferation of fake news on social media platforms. A socially influenced information verification practice, such as checking for comments and validating information to family, friends, or other users, strengthens the tendency of SMUs to rely on others to confirm or determine the factuality of the information. This finding supports the preference of SMUs who consider news links and recommendations from friends and family compared to those posted by journalists or news organizations. Moreover, social influence has also contributed to the belief of SMU in the information posted online.

Based on the experiences of SMUs with fact-checking websites, the general findings of this study confirmed that they are easy to use. This implies that the majority of the SMU agreed with how easy it is to confirm or determine the truthfulness of the information based on the social media posts and websites of the fact-checking programs, particularly Rappler and VeraFiles. Although the 2019 Reuters Institute’s Digital News reports showed that more than half of the 38 countries studied have concerns about the ability to discern what is real and fake on the Internet (Newman et al., 2019), it can be posited that when fact-checking presents information, it can help readers to discern the truthfulness of the information. Perceived ease of use is not a significant concern for fact-checking services or programs. A more pressing issue is the identification of misinformation on social media platforms. With the competing information on the web or social media, the presentation of materials is essential to hasten the user interface. In that way, users can easily engage in the information presented.

Although the survey generally perceived fact-checking as useful, there are aspects where fact-checking services were considered useless. In this study, perceived usefulness as a construct can be considered to the degree to which the service supports users in their goals (Brandtzaeg et al., 2018). It is the degree to which SMUs can discern the factuality of information from the online content posted on social media platforms. In one of the interviews with SMUs about the use of fact-checking websites, the response was, “I do not usually use it to verify because it is easier to search using Google.” Although SMUs find the fact-checking website useful, they are less significant during the verification process. This is because information on social media may not be found on fact-checking sites. Instead, a search engine was considered an alternative.

The perception of SMU influenced the adoption and usage of fact-checking services. Brandtzaeg and Følstad (2017) confirmed that positive perception is associated with the usefulness of fact-checkers, while negative perception is associated with untrustworthiness. Therefore, this study’s result recommends the need to establish these perceptions. In the United States, political ideologies also differ regarding attitudes to fact-checking. For instance, mainstream liberals are more likely to report using fact-checking websites than do conservatives, who consider it less useful (Robertson et al., 2020). Clearly, it shows that fact-checking perceptions depend on the beliefs and background of an individual or group. Establishing a good reputation and credibility in the perception of SMUs can prove the goal of fact-checking services.

While addressing fake news, misinformation, and related phenomenon is the right thing to do, the adversities are challenging. The velocity and volume in the production and distribution of online information, including fake news, outpaces fact-checkers. With a handful of recognized fact-checkers, it is indeed challenging to address. A fact-checking process is a bottom-up approach that entails the need to peruse information as objectively as possible. Fact-checking, therefore, is a vital ingredient in identifying factors for a social information system that promotes the culture of truth in the public sphere. It is alarming, though, that the trust rating of existing fact-checkers in the Philippines is low.

7. CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

This study’s key findings pertain to the practices of SMUs and their perception of fact-checking services in the Philippines. With the belief that fact-checking services must be credible, this study provides evidence of the perceptions of SMUs. Perception is important because the usage of fact-checking services depends on their credibility. The significant findings are summarized into major points, as explained in the succeeding paragraph.

First, the themes that emerged as the practices of information verification show two crucial perspectives on the proliferation of “fake news.” Verifying through cross-checking is an example of a practice that may limit the spread of fake news. Confirmation from personal and social networks may indicate a possibility of spreading misinformation. Although there are recommended practices, awareness of fact-checking and being critical of the information posted on social media allows one to double-check the information found on social media.

Second, although around 54% of the respondents are aware of fact-checking programs (Rappler and VeraFiles), only 48% of the respondents have experienced using them. In one of the interviews, awareness of fact-checking is a reminder that not all information posted on social media is factual. Awareness itself is an indicator that SMUs are critical of information encountered on social media.

Third, fact-checking services are generally perceived as easy to use and valuable. The practice of summarizing information and labeling it with diagonal text such as “Misinformation,” “Needs context,” or “False” makes it easier for the user to assess the image or report they encountered on social media. However, because the information that SMUs want to be clarified is sometimes absent from the website, they tend to consider it less valuable than the ease of use.

Lastly, SMUs are ambivalent about perceived trust in fact-checking services provided by Rappler, VeraFiles, and even some mainstream media fact-check posts. This can be attributed to fact-checkers being critical of the government while the president has the majority of the support of the Philippine population based on surveys. SMUs in Mindanao tend to favor government programs because they support the president from Mindanao.

Although this study has shed light on the perspective of SMUs regarding fact-checking services, it also provides some limitations. Due to the limitations of COVID-19, recruitment for the interviews was limited. The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalization of the results. Moreover, the data collected may be reflective only at the time of data collection. However, in general, it provides insights into the perspective of SMUs on fact-checking services as one of the ways to address fake news on social media platforms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Mindanao State University – Iligan Institute of Technology as well as the Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation through De La Salle University for their financial support and guidance in the conduct of research. Moreover, we are thankful to the participants, especially for those who participated during the interview, for trusting the researchers in sharing their experiences.

REFERENCES

(2019) How to do thematic analysis: Step-by-step guide & examples https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/#:%E2%88%BC:text=Thematic%20analysis%20is%20a%20method,meaning%20that%20come%20up%20repeatedly.

(2019) Filipinos spend most time online, on social media worldwide - Report https://www.rappler.com/technology/222407-philippines-online-use-2019-hootsuite-we-are-social-report/

(2020) Digital 2020: The Philippines https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-philippines

(2018) Facebook partners with Rappler, Vera Files for fact-checking program https://www.rappler.com/technology/social-media/200060-facebook-partnership-fact-checking-program

(2017) ContentCheck: Content management techniques and tools for fact-checking https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01596563/document

, , (2022) News consumption and behavior of young adults and the issue of fake news Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 10(2), 1-16 https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTaP.2022.10.2.1.

, (2018) Architects of networked disinformation: Behind the scenes of troll accounts and fake news production in the Philippines Communication Department Faculty Publication Series, 74 https://doi.org/10.7275/2cq4-5396.