1. INTRODUCTION

In the countries of the Mekong Subregion, notably Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, significant cultural affinities are evident, originating from geographical, cultural, religious, and lifestyle congruities. These shared foundations have evolved through continuous cultural interactions driven by visits, trade, and migration, leading to the assimilation of diverse traditional and contemporary cultural traditions (Greater Mekong Subregion Secretariat, 2013). Linguistic commonality is a notable illustration of this shared culture, where historically influenced alphabets and words, particularly Sanskrit, facilitate communication and mutual comprehension among the populations. Additionally, performing arts and musical traditions exhibit remarkable resemblances, seen in dance performances and musical instruments influenced by each other, adapted to harmonize with each nation’s cultural heritage. Furthermore, there is convergence in observing various customs, beliefs, and rituals across these nations, exemplified by traditions such as Songkran and the Twelve Months Tradition, known as Heet Sipsong Klong Sib Si, observed comparably across all three countries (Prasarn et al., 2015). These shared cultural commonalities serve as powerful tools for promoting unity, mutual understanding, and long-lasting collaboration across various domains, establishing a solid foundation for strong and sustainable partnerships in the future.

In this study, we utilize the term common culture to describe a collective cultural foundation characterized by shared elements that transcend individual ownership, aligning with the conceptual framework outlined by Bertacchini et al. (2012). Within this framework, our analysis identifies recurring components such as shared historical narratives, common values, principles, objectives, and a deep understanding of specific traditions and practices, as detailed by McLean (2015).

When analyzing the cultural information systems in the mentioned countries, it is evident that they primarily function as general search tools, albeit with limitations. They mainly employ a character comparison technique called “string matching” for information retrieval, often overlooking nuanced semantics and conceptual intricacies associated with search terms. Consequently, this approach yields unsatisfactory results for specific search queries, particularly concerning traditional terms with multiple spellings. This semantic disparity, often referred to as the “semantic gap” in Hein (2010)’s work, underscores the importance of implementing knowledge organization (KO) strategies to address this challenge effectively.

In the domain of KO, the thesaurus stands as a pivotal instrument, playing a central role in the organization, categorization, and structuring of information and knowledge, thereby enhancing accessibility and comprehensibility for users (Bergamaschi et al., 1999). Thesauri establish meaningful relationships between terms and concepts, facilitating efficient information retrieval and enabling users to navigate complex knowledge domains through mechanisms such as broader terms (BT), narrower terms (NT), and related terms (RT). Moreover, the development of specialized vocabularies for diverse domains, including information science and information services, follows a structured and systematic process encompassing vocabulary selection, analysis, synonym identification, establishment of word relationships, refinement, scrutiny, and integration of expert input (Ahmad et al., 2020).

Constructing a thesaurus for the subject of the traditional common culture of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) is paramount for researchers, scholars, educators, policymakers, and cultural enthusiasts. First, such a thesaurus facilitates efficient KO and retrieval by providing a structured framework for categorizing and indexing terms related to cultural practices, traditions, and customs within the region. Second, it enhances accessibility to cultural heritage resources by enabling users to navigate through a comprehensive vocabulary that encompasses various aspects of the traditional culture of the Mekong Subregion countries. Lastly, the thesaurus serves as a valuable tool for researchers, educators, students, and individuals interested in studying or preserving the cultural heritage of the region, offering a standardized terminology for communication and research purposes.

Furthermore, the research encompasses the creation of specialized vocabularies tailored to specific cultural groups, as exemplified by Arayapant (2019)’s endeavors in analyzing the vocabulary structure of the Tai ethnic group and formulating terminology related to their cultural knowledge, thus demonstrating the versatile application of KO principles across various domains and disciplines. Additionally, the organizational structure inherent in the thesaurus format holds potential for further development into an ontology, as explored by Li and Li (2013). Therefore, this study not only involved the organization of terminologies about the traditional common culture of the GMS, but also underscores the thesaurus format’s utility as a resource for exploring the relationships within cultural heritage content. It serves as a tool for accessing and retrieving knowledge about cultural heritage within databases and on the Internet. Moreover, the findings obtained pave the way for further development into an ontology and semantic search system.

2. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

This research aimed to analyze the vocabulary related to the common culture and traditions of the Mekong Subregion countries, determine the structure, and develop a thesaurus to create a digital thesaurus of the traditional common culture of the GMS.

3. METHOD

In this research, thesaurus development follows a seven-step structured process, applying the thesaurus construction guidelines, which provide an important and valuable guide to content discovery, organization, and retrieval, encompassing common activities across all fields, including cultural heritage (Autiero et al., 2023; Ryan, 2014) (Table 1).

Table 1 provides an overview of the structured seven-step process involved in the development of the thesaurus for cataloging the traditional common culture of the GMS.

4. RESULTS

The structure of common cultural knowledge categories regarding traditions of the Mekong Subregion countries was developed according to the concept of characteristics of a common culture through content analysis and the application of KO principles. The results of developing the knowledge structure of the common culture and traditions of the Mekong Subregion countries are presented in the form of relative vocabulary. The research findings are as follows.

4.1. Knowledge Structure of Common Culture in the Mekong Subregion

The outcomes of the knowledge structure development encompass a comprehensive framework consisting of 13 distinct categories of knowledge (Table 2). Table 2 lists various categories encompassing knowledge related to the traditional common culture of the GMS. These categories serve as key components for organizing and cataloging information about the rich cultural heritage present in the Mekong Subregion.

The subsequent phase entails the creation of a category structure, presented either as a category display or categorized framework. This process aligns with the principles of classification and categorization elucidated by Rowley (1992). This structured framework delineates an organized dataset, revealing the hierarchical relationships among various groups within the system. This meticulously designed structure encompasses 13 overarching categories, further segmented into 37 subcategories, and intricately branching into 43 distinct subgroups (Table 3). By adopting this hierarchical arrangement, users will benefit from a coherent and ordered presentation, affording them a systematic means to explore and navigate the extensive reservoir of information encapsulated within the traditional common culture of the GMS.

Shared cultural knowledge structure of traditional common culture within the Greater Mekong Subregion

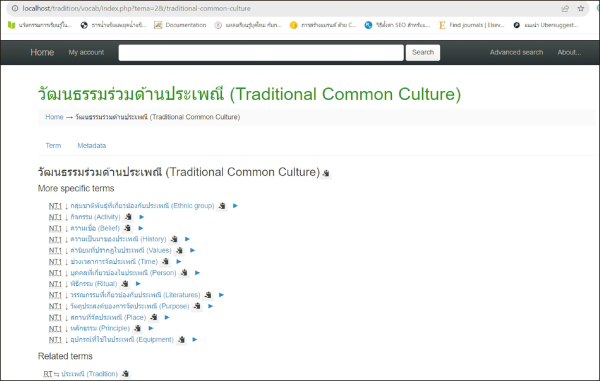

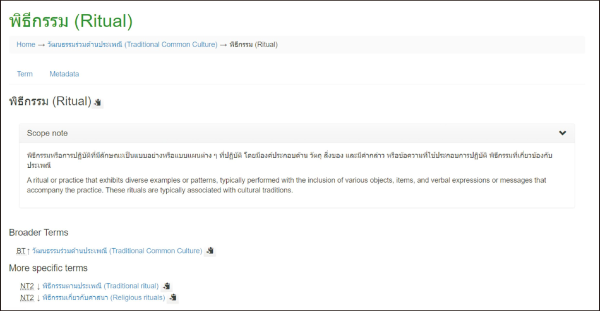

The knowledge framework was subsequently transformed into a thesaurus format, structured around conceptual interconnections and word relationships. These relationships encompass hierarchical associations and coequal linkages, as well as mutually interconnected or RT. To elucidate these relationships, the thesaurus employs symbols such as BT to signify higher-level concepts, NT to denote subordinate concepts, and RT to indicate associated terms (Fig. 1).

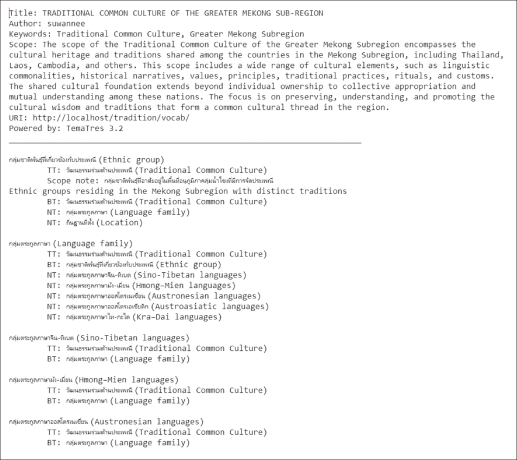

In pursuit of enhancing the quality of the grouped vocabulary, the researcher meticulously refined it based on valuable input and recommendations provided by domain experts. Subsequently, efforts were directed towards the digitization and development of this vocabulary into an electronic format. This transformation was facilitated through the utilization of the TemaTres program—a versatile open-source software designed to assist in the creation of web-based vocabulary management systems. TemaTres is adept at accommodating both general and relational vocabularies, rendering it an ideal tool for this purpose.

4.2. Traditional Common Culture Digital Thesaurus

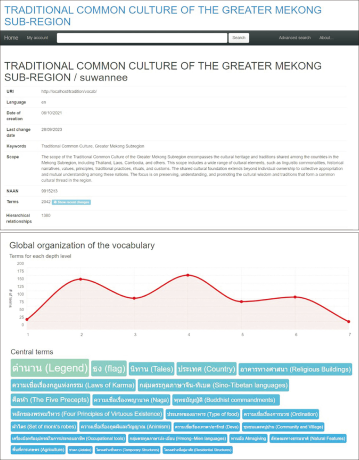

The TemaTres web-based vocabulary management system identified, compiled, and classified a total of 2,042 principal words related to the traditional common culture of the GMS into terms for each of the seven deep levels, with 1,380 found to have hierarchical relationships (Fig. 2).

The digital thesaurus of the traditional common culture of the GMS represents a significant advance in KO and accessibility within the GMS. This report provides an overview of the system as a whole, including details such as the number of words in the corpus, the number of relationships between the words in the corpus, and the depth of the vocabulary.

The digital thesaurus platform effectively managed the controlled vocabularies related to the traditional common culture of the GMS by storing both Thai and English vocabularies. Upon retrieval, the platform displays the vocabulary along with details of BT, NT, RT, cross-references, and scope notes (Figs. 3-4).

4.3. Evaluation of the Traditional Common Culture Digital Thesaurus

Efficiency testing employs the gold standard evaluation method for information search systems, which is assessed by graduate students and researchers. This method involves examining search results from selected documents or datasets categorized as either relevant or non-relevant. The evaluation process measures search efficiency using parameters such as precision (Precision), recall (Recall), and the overall effectiveness of the system (F-measure). The query selection of the term aims to demonstrate the system efficiency in terms of the stored data. In this research, 14 sets of vocabularies were sampled for retrieval from corpora, as shown in Table 4.

Results of the performance evaluation of the traditional common culture digital thesaurus as evaluated by graduate students and researchers

In Table 4, the performance evaluation of the traditional common culture digital thesaurus is demonstrated through precision, recall, and F-measure. Precision assesses the accuracy of retrieved results, calculated as the ratio of relevant documents retrieved to the total number of documents retrieved. An average precision of 0.94 indicates that, on average, 94% of retrieved items were relevant to the query categories. Recall measures the completeness of the retrieval process by determining the ratio of relevant documents retrieved to the total number of relevant documents in the collection. With an average recall of 0.88, the system successfully retrieved, on average, 88% of relevant items in the collection. The F-measure, representing the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offers a balanced score reflecting both precision and recall. It is calculated using the formula:

With an average F-measure of 0.90, the retrieval system demonstrates well-balanced performance across query categories, achieving a commendable balance between precision and recall.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Throughout this study, our primary aim has been to develop a digital thesaurus of the traditional common culture of the GMS. By comprehensively understanding the common culture among the countries of the Mekong Subregion and meticulously analyzing and organizing cultural knowledge according to established frameworks, we have aimed to achieve this goal. Through our research, we have highlighted the importance of KO, with the thesaurus playing a central role in organizing, categorizing, and structuring information and knowledge, ultimately enhancing accessibility and comprehensibility for users.

Developing a knowledge structure on terminology related to cultures and traditions shared between 13 countries in the GMS requires a deeper delve into the classification of knowledge within cultural boundaries. This necessitates reference to the framework established by the Organization for Science Education and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which divides cultures into seven distinct groups: language, performing arts, traditional crafts, folk literature, Thai wisdom, sports, social norms, rituals and festivals, as well as knowledge and practices related to nature and the universe. Additionally, it is imperative to consider the structural framework proposed by Iamkhajornchai and Manmart (2016) for the organization of Thai cultural knowledge. This framework classifies cultural knowledge into four groups, namely the cultural heritage knowledge group, art knowledge group, media knowledge group, and groups of creative work knowledge, based on the inherent nature of the work. It becomes evident that there exist disparities between the domains of knowledge covered by the relational terms in this research, which are exclusively tailored to the realm of knowledge linked with traditions. Should we contemplate the organization of this relative vocabulary within the framework of the aforementioned cultural groupings, it can be posited that common cultural traditions align with the category of social practices, ceremonies, and festivals according to UNESCO’s conceptualization. Moreover, they fall within the cultural heritage knowledge group when contextualized within the framework for the systematization of Thai cultural knowledge.

The approach employed in this research involves the initial development of a relational lexicon, followed by the transformation of words from this lexicon into an ontology. This methodology effectively reduces the intricacies associated with ontology development (Huang et al., 2008), aligning with the findings of Li and Li (2013) in their study “On transformation from the thesaurus into domain ontology.” Their study delves into the transition from lexical relations to ontology, elucidating how both lexical relations and ontology can be exploited to expound upon information related to meaning and knowledge.

Creating a lexicon serves as the foundational step for ontology development, offering significant time-saving advantages. Terms contained within the relational lexicon database can be seamlessly converted into ontology classes or concepts. For instance, the symbol “BT” can be equated to “Sub Class of,” representing data relationships within a descending hierarchy. This approach stands as a valuable resource for researchers embarking on vocabulary development and the subsequent evolution into ontology in future research endeavors. Furthermore, the structuring of lexical knowledge in this research aligns with the concept of the Library of Congress Classification system, which is essentially a practical system. In this system, categories are assigned when a book is introduced into the library. If a particular category has no books associated with it, it will lack group numbers within that category (Chan et al., 2016; Mischo, 1982).

This approach implies that the analysis of vocabulary, aimed at developing the relational lexicon in this research, is an ongoing process. Vocabulary analysis is conducted based on information resources available at the present moment. However, it is important to note that if additional information resources related to common cultures emerge in the future or if there are new knowledge groups distinct from the existing ones, they can be seamlessly incorporated. This ensures that the relational vocabulary remains comprehensive, complete, and continually updated to reflect the evolving landscape of knowledge.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

Navigating the realm of knowledge concerning the traditional common culture of the GMS demands effective tools and strategies, with relational vocabulary emerging as a cornerstone for facilitating efficient knowledge retrieval and exploration. As cultural understanding deepens, the need for precise terminology becomes increasingly apparent. Recommendations for its use are as follows:

-

1) Information repositories housing resources on the traditional common culture of the GMS play a crucial role in facilitating global knowledge access and cultural heritage preservation. Relational vocabulary acts as a vital tool in defining terms that encapsulate the essence of these resources. Moreover, professionals such as librarians, informaticists, and information specialists can utilize the inherent structure of relational terms to organize information resources effectively and develop robust search systems, thus enhancing accessibility for a global audience and contributing to the preservation of cultural heritage while enriching global understanding of the region’s diverse heritage.

-

2) Researchers, academics, educators, students, and individuals worldwide who are interested in the common culture of the GMS can harness this specialized vocabulary to unlock valuable insights and promote cultural understanding. The comprehensive range of terms within the relational vocabulary provides users with an in-depth understanding of relevant concepts. Additionally, the interconnected nature of these terms facilitates further exploration across various information repositories, improving the efficiency of knowledge retrieval and exploration for a global audience and fostering cross-cultural understanding and appreciation. By recognizing the importance of interconnectedness, we can bridge cultural divides and promote mutual respect and understanding across diverse communities.

In conclusion, navigating the knowledge related to the traditional common culture of the GMS requires effective tools and strategies, with relational vocabulary emerging as a cornerstone for facilitating efficient knowledge retrieval and exploration. Recommendations for its use have been outlined, emphasizing the pivotal role of information sources and professionals in leveraging relational vocabulary to support knowledge retrieval, and demonstrating the importance of harnessing this specialized vocabulary for accessing and retrieving knowledge. By implementing these recommendations, stakeholders can enhance their understanding and exploration of the cultural heritage of the GMS, contributing to its preservation and dissemination for generations to come.

REFERENCES

, , , (2020) The impact of controlled vocabularies on requirements engineering activities: A systematic mapping study Applied Sciences, 10, 7749 https://doi.org/10.3390/app10217749.

, , , (2023) The seven steps: Building the DiGA thesaurus Journal of Open Humanities Data, 9, 11 https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.111.

, , (1999) Semantic integration of semistructured and structured data sources ACM SIGMOD Record, 28, 54-59 https://doi.org/10.1145/309844.309897.

Greater Mekong Subregion Secretariat (2013) About the Greater Mekong Subregion program https://greatermekong.org/about-greater-mekong-subregion

, (2016) Cultural knowledge organization system Journal of Information Science Research and Practice, 31, 93-122 https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jiskku/article/view/45938.

, (2013) On transformation from the thesaurus into domain ontology Advanced Materials Research, 756-759, 2698-2704 https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.756-759.2698.

(1982) Library of congress subject headings: A review of the problems, and prospects for improved subject access Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 1(2-3), 105-124 https://doi.org/10.1300/J104v01n02_06.