1. INTRODUCTION

Information-seeking behaviour involves finding and gathering information to suit user needs. Information professionals have examined how people search for information and created models to reflect these searches. Bates (1989) introduced “Berry Picking,” where information users constantly search and accumulate data until they find complete, relevant information that meets their needs. In contrast, Ellis and Haugan (1997) described the multiple stages of information-seeking, including tracking, connecting, investigating, and organizing outcomes. Depending on the time, one may perform these tasks in different sequences. Kuhlthau et al. (2008) developed the information search process in the 1980s and revised it in 2008 by applying it to a digital environment. She described informational behavior as a physical activity that relies on one’s emotions, interests, and ability to make decisions about a variety of information sources. Nicholas et al. (2000) also showed that ubiquitous web data has transformed information-seeking. Although Nicholas considers information behaviour during online interactions—where users primarily seek information on websites—this model is consistent with Choo et al. (2000). Users choose a search engine to meet their information needs, skim content, and carefully evaluate material before downloading anything useful. Wilson (1999) talked about information behavior, which includes discovering and acquiring information.

Researchers have used information behaviour or information-seeking models to study the information-seeking behaviour of different professional or user groups. Police officers’ information-seeking behaviour was studied by Guclu and Can (2015). Officers typically used office documents and fellow officers for information, not books, journals, or other official sources. Sahu and Nath Singh (2013) showed that Indian astronomy and astrophysics experts use astronomical data platforms to meet their research and instructional objectives. Folorunso (2021) explored how doctors seek patient treatment information and improve healthcare delivery. They found that doctors sought information based on specialty, age, gender, and employment experience. In a comparable a similar direction, Adongo et al. (2022) discovered a substantial correlation between the health-seeking behavior of patients and the utilization of public and private health facilities in relation to their socio-demographic characteristics (gender, marital status, education, and income). Lavranos et al. (2015) examined artists’ information-seeking behaviour during genre composition. In addition, a recent study on the information-seeking behaviour of sacred artefact enthusiasts in Thailand found that Thai people adore sacred artefacts because they believe these items can improve their academic and business success (Chitiyaphol & Kwiecien, 2023). Chanchai et al. (2023) found that Thai women worship sacred stones to improve their work and education. Similar to Kalchankit and Taiphapoon (2016), Chanchai et al. (2023) also investigated the use of lucky stone jewellery to enhance work and study performance. Both studies found that participants learned from people and online social networks. This contradicts Tosomboon and Rungkhunakorn (2021), who found that amulet collectors study amulets for religious reasons. They begin by reading literature and consulting with amulet experts, and then buy actual amulets to study, compare, or fulfill other needs.

Buddhist-related enterprises have grown significantly due to the strong belief in and reverence for these amulets (Kerdnaimongkol, 2017; McDaniel, 2011; Sawangsri, 2006; Yurungruangsak, 2012). These businesses utilize Buddhist-related objects or symbols to generate profit and gain competitive advantages. To respond to the desires of individuals seeking blessings in various areas of their lives, such as their careers, education, fortune, or safety, a profitable approach is to offer the rental or purchase of amulets, focusing on the belief in their sacredness (Taisrikhot et al., 2020). The trade of amulets has gained significant popularity in Thai society and abroad. The prices of amulets advertised on temple boards, in magazines, or on websites usually span from hundreds to millions of Thai baht. The cost of acquiring an amulet is variable and depends on the level of satisfaction experienced by the collectors (The Standard Wealth, 2021). Several factors influence the price of renting or purchasing sacred artefacts, including the condition of the amulets (no cracks, chips, or scratches), their reputation or popularity among enthusiasts, their aesthetic beauty in Buddhist art, and their age (Anansiriwat, 2016; Aranyapoom, 2017; Chantanee, 2016). Moreover, pilgrimage travel, along with amulet marketing, can boost the economy. The Public Relations Department of Thailand estimated a value of 10,800 million baht in 2019 ($300 million US dollars) and increased global recognition. Future Markets Insight (Bangkok Business Media, 2023) predicted that global faith-based tourism will be worth 1.37 trillion US dollars by 2025. This is expected to triple in a decade, reaching 40.9 trillion US dollars by 2035.

As a result of the previously mentioned shifts in beliefs and economic worth, collectors now have a heightened demand for knowledge regarding amulets. Their interest involves acquiring knowledge about legends, tales, and associated stories, along with methods for verifying the accuracy of these items. Duplicates are increasingly prevalent due to the growing scarcity of unique objects. Hence, collectors now require accurate information and information technology to verify or suggest authentic amulets.

Therefore, gaining insight into the information search behaviour of users will enable information professionals to customise information services and systems that align with the varied information-seeking behaviours of users. According to previous research, people who search for specific information, such as various beliefs, often have different information-seeking behaviours compared to those who use information about general topics. Hence, the researchers aims to investigate the diverse information-seeking behaviours exhibited by amulet collectors with distinct characteristics. Based on the study findings, we will further enhance the semantic search system to encompass a wide range of behavioural patterns observed by amulet collectors.

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

The main objective of this study is to evaluate and examine the socio-demographic factors that influence the information-seeking behaviour of amulet collectors in Thailand. Since this research is a preliminary study in the design and development of the amulet semantic search system, its focus is solely on examining the information-seeking behaviour related to amulets. It excludes the utilisation of information about amulets. This study addresses the following research questions and hypotheses:

2.1. Research Questions

1. What are the primary sources users use when seeking information regarding amulets?

2. What is the impact of various socio-demographic factors on information-seeking behaviour?

3. What is the correlation between the socio-demographic aspects of amulet collectors and their information-seeking behaviour?

2.2. Hypothesis

Prior research has identified personal characteristics such as gender, age, educational level, field of study, occupation, and income level as influencing information-seeking behavior. This research exclusively selected socio-demographic characteristics that influence the information-seeking behavior of sacred object collectors: gender, age, occupation, and educational background. The following hypotheses were formulated and utilized as a framework for the research study:

H0: There are no evident differences in the information-seeking behaviours among amulet collectors, regardless of their characteristics, including gender, age, subject background, and occupation.

H1: The objectives of amulet collectors in seeking information vary significantly depending on their gender, age, academic discipline, and occupation.

H2: The information sources utilised by amulet collectors are significantly influenced by variables such as gender, age, academic background, and occupation. Amulet fans usually rely on personal sources of information to acquire knowledge about amulets. With the exception of academic groups, only information sources such as books or journal articles will be utilised.

H3: Gender, age, academic discipline, and occupation have significant effects on the information-seeking behaviour of amulet collectors.

H4: Occupation and academic discipline have a more significant positive influence on information-seeking behaviour about amulets than gender and age.

3. DEFINITION OF VARIABLES IN THIS RESEARCH

3.1. Amulet Collector

An amulet collector refers to a person who collects amulets or is interested in information about amulets. The purpose may be to collect amulets for personal reasons or to pursue academic goals.

3.2. Auspiciousness

Auspiciousness means acquiring knowledge about amulets with the aim of increasing the happiness and motivation of amulet collectors to practice according to the principles of Buddhism.

3.3. Faith in Amulets

Faith in amulets means seeking information about amulets to satisfy the desire for good things in one’s life, such as success, wealth, safety, and so on.

3.4. Social Engagement

Social engagement refers to the active participation and interaction of individuals in social activities, such as conversations, events, or community initiatives. Wearing amulets, similar to wearing jewellery, is a way to socialise and earn acceptance among others who value them. Furthermore, it functions as a mirror of the collector’s societal and financial standing.

3.5. Data Verification

Data verification is the business procedure of checking the version or appearance of amulets. Data verification has a significant impact on the value of purchasing and selling amulets. Should the amulet possess rarity or be in high demand, its price will correspondingly be elevated.

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1. Population and Sample

This study adopted a quantitative research methodology to examine the information-seeking behaviour of individuals who collect amulets. The researchers chose a simple random sampling technique from those interested in collecting amulets. A sample size of 384 persons was selected with a 95% confidence level, representing an unknown population.

4.2. Research Instruments

The researchers developed a questionnaire to collect data on information-seeking behaviours. The questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part includes the personal data of the respondents, which will be used as a variable to analyze individual characteristics that impact information-seeking behaviour. The second part inquires about the specific objectives and preferred sources of information utilized by amulet collectors. The third part focuses on the information-seeking behaviour derived from Ellis’s information-seeking behaviour model.

The questionnaire is comprised of two sections: multiple-choice questions and a final section of questions presented on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Three experts specializing in information-seeking behaviour evaluated the content validity of the questionnaire through the utilization of item-objective congruence analysis. A score of 0.93 suggested that the content validity was sufficient for data collection. The researchers evaluated the questionnaire’s reliability by examining the alpha coefficient, utilizing data collected from 30 people with the same characteristics as the sample group. The reliability, shown by a value of 0.978, was determined to be sufficient for collecting study data.

4.3. Data Collection

The researchers distributed the online questionnaire and encouraged its completion among amulet collectors or enthusiasts through online social networks. The term “amulet collectors” in this study refers to individuals who collect, believe in, study, or research various kinds of amulets. Consequently, the researchers published an online questionnaire on the Amulets Club’s social network, a community for individuals who are interested in, intrigued by, or hold faith in amulets. The online questionnaire was chosen due to Thailand’s implementation of social distancing measures from January to February 2022 in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. A total of 378 individuals completed the questionnaire. Subsequently, the questionnaires were carefully reviewed to ensure precision and to identify any missing data, resulting in a final count of 375 respondents for analysis.

4.4. Data Analysis

Percentages were used to represent the participants’ data, their purposes for seeking information, and the sources they used. Mean and standard deviation were used to examine information-seeking behaviour. t-test, one-way analysis of variance, and chi-square statistics were used to examine the differences among the investigated variables. Furthermore, structural equation modelling was employed to explain the impact of individual variables on amulet collectors’ information-seeking behaviour. The construct validity was assessed using principal component analysis and Varimax rotation techniques, employing Kaiser Normalisation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value of 0.952 suggests that the correlation matrix was appropriate for analysis.

Ethical approval: The research project code for this study is HE623117, and it was granted ethical approval on December 20, 2021.

5. FINDINGS

5.1. Demographic Information

Of the 375 respondents, 267 (71.0%) were men, while the remaining 109 (29.0%) were women. A total of 125 respondents (33.2%) were between 41 and 50 years old, followed by 86 respondents (22.9%) between the ages of 31 and 40, and 68 respondents (18.1%) younger than 21. An examination of the respondents’ fields of study revealed a similar distribution. Of these, 194 respondents (51.6%) studied science and technology, while 182 respondents (48.4%) focused on the humanities and social sciences. The majority of the sample, 153 respondents (40.7%), worked as business owners or general employees. Additionally, 113 respondents were affiliated with universities or educational institutions, and another 110 had specific occupations such as doctors, nurses, police officers, or soldiers.

5.2. Comparing the Differences in Distinct Characteristics of Users Regarding Their Objectives in Seeking Information

Regarding RQ1, the primary sources users used to obtain information about amulets, and H2, the information-seeking objectives among amulet collectors, showed significant differences in gender, age, academic background, and occupation. The researchers assessed and compared differences in users’ objectives when obtaining information regarding amulets. They conducted a comparative analysis of four variables: gender, age, occupation, and educational background.

The study found differences between women and men in seeking knowledge about amulets in terms of social participation and good luck. The data in Table 1 showed that 14.7% of women searched for information about amulets and participated in social activities more than men did (11.6%), and women (71.6%) searched for information about amulets more than men did (60.7%). No differences were found between men and women for other purposes, such as career objectives, purchasing amulets, or supporting work duties.

Differences in objectives in seeking information about amulets among respondents of different genders

Table 2 shows that people under 21 are less objective when searching for information regarding purchasing amulets (8.8%), career support (10.3%), and auspiciousness (51.5%) than are other age groups. For example, individuals under 21 had just 8.8% of their objectives in this sector, while those over 50 had 47.3% of their goals related to collecting data for purchasing and selling amulets. People aged 21 to 30 are 83.3% more likely to seek a prosperous future, compared to 51.5% of those under 21. People over the age of 41 are more likely to obtain data that confirms the validity of amulets than any other user group. According to the study, individuals of various ages seek information for a variety of reasons. The objective of information search differs, with statistical significance set at 0.05.

The respondents’ information-seeking objectives varied depending on their occupation. Table 3 shows that the academic group had fewer information-seeking aims than the other occupational groups, with statistical significance at the 0.05 level. Specifically, 11.6% of academics seek information to buy amulets, 14.3% to support their work, and only 6.3% to participate in society. Researchers discovered that 43.6% of professional groups and 32.5% of business owners specifically seek information about purchasing amulets. This is much greater than the academic group at the 0.001 level. Furthermore, just 6.3% of academics seek information on amulets to participate in society, compared to 20.0% of professionals and 11.7% of business owners, with statistical significance at the 0.008 level. This represents an acceptance of H1 (Table 3).

Differences in objectives for seeking information about amulets among respondents with different occupations

Table 4 shows that participants from different academic disciplines had different information-seeking objectives. When comparing the academic subjects of the humanities and social sciences with those of science and technology, the study revealed a statistically significant difference at the 0.01 level. Four point nine percent of those from humanities and social sciences backgrounds sought information about amulets, compared to less than 19.6% of the science and technology group. The results of studies on auspiciousness reveal a different picture. Seventy-five point eight percent of people with humanities and social sciences backgrounds seek out information about auspiciousness, up from 52.6% of people with science and technology backgrounds. The study’s results confirm the acceptance of H1.

Differences in objectives for seeking information about amulets among respondents with a different field of study

The study found that age, gender, education, and occupation affected information-seeking aims. Women are more likely than men to learn about amulets, mostly for socializing or luck. Young amulet collectors are more likely than older collectors to research amulets for trading, good fortune, verification, or support. Academic institutions researching amulets for trading and work share similarities with individual amulet collectors, despite their lower social interaction. Science and technology amulet collectors prefer amulets that allow them to participate in society and bring more luck compared to those from the arts and social sciences. Thus, the study supports the hypothesis. Consequently, the findings of the study provide evidence in support of the stated hypothesis.

5.3. Analyzing the Selection of Information Sources Among Participants with Varying Personal Attributes

According to H2, the information sources used by amulet collectors differ significantly based on gender, age, subject, and occupation. Hence, the researchers undertook a comparison of the information sources used by those interested in amulets during the era of digital technology. The results of this study revealed significant differences, as outlined below.

Table 5’s data reveals that men prefer to use information sources from online social networks the most (50.9%), followed by amulet experts (42.7%), while women prefer to use friends or family (49.5%), which is similar to using online social networks (48.6%). However, at the 0.05 level, there was a statistically significant difference between men and women in choosing to use the amulet market. Specifically, 10.1% of men use the amulet market as an information source, compared to 3.7% of women. In Thailand, the amulet market serves as a hub for men who have a strong passion for amulets. As a result, women amulet collectors often do not prefer to use this type of information source.

Differences in information sources/resources for seeking information about amulets among respondents of different genders

Table 6 shows that amulet collectors of various ages have distinct preferences for information sources. The study found that people under the age of 21 (42.6%), those aged 41 to 50 (62.4%), and those aged 50 and older (60.0%) were the most likely to use online social networks as their primary information source. On the other hand, amulet collectors aged 21 to 30 (61.9%) prefer to use monks as their main source of information. While those group aged 31 to 40-year-olds (52.3%) chose to use amulet experts. Chi-square analysis was used to examine the differences between users of different ages and their information sources at the 0.05 level. The research findings revealed a statistically significant variance in the selection of information sources across age groups. People under the age of 21 rely on their friends and family for knowledge and consult with fewer specialists than other age groups. Meanwhile, respondents aged 21 to 30 were more likely to seek information from a monk on amulets than other age groups. Furthermore, respondents under the age of 21 and those over the age of 41 are more likely to utilize social media platforms to acquire information about amulets than those between the ages of 21-30 and 31-40. This represents an acceptance of H2.

Differences in information sources/resources for seeking information about amulets among respondents of different age groups

Table 7 shows the engagement of several career groupings and the numerous information sources selected. Professionals used amulets and online social networks the most (50.9%), followed by inquiries from friends or family members (40.9%). The self-employed or private business group, on the other hand, chose to seek information from friends or family members the most (51.3%), mirroring the preference for online social networks (50.0%). The majority of academics (50.0%) preferred to use online social networks, followed by consultations with monks (38.4%).

Differences in information sources/resources for seeking information about amulets among respondents of different occupations

When the information source choices of different occupational groups were compared, the research results revealed differences. Entrepreneurs, for example, preferred to obtain information from friends and family, publications, and the amulet market over other occupations. In contrast, the academic group used information sources such as experts, books, and amulet clubs less frequently than the other professional groups. This supports H3, which states that different occupations have distinct effects on the selection of information sources while seeking information. At the 0.05 level, this difference is statistically significant.

Respondents with various academic backgrounds chose different information sources. Respondents with a background in science and technology chose social networks as the most common source of information (42.3%), followed by monks (40.7%) and close friends or family (40.2%). In contrast, respondents with a background in humanities and social sciences also chose social networks as the most common source of information (58.8%), followed by advice from amulet experts (48.4%).

When statistical differences were examined, the research findings revealed that respondents from diverse academic backgrounds used distinct information sources. Respondents in the humanities and social sciences were more likely than those in science and technology to rely on online social networks and experts for knowledge. Table 8 exhibits statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

5.4. Comparing Information Seeking Behaviours of Respondents with Different Personal Characteristics

H3 suggests that gender, age, academic background, and occupation significantly affect the information-seeking behaviour of amulet collectors. The researchers analyzed and compared the differences in information-seeking behaviour patterns related to amulets. Respondents with varying personal characteristics exhibited diverse information-seeking behaviours. In this study, the researchers utilized Ellis and Haugan (1997)’s information behaviour model as a framework, which involves the eight stages of information seeking.

Table 9 shows the information-seeking behaviour of respondents of various genders using Ellis. The results revealed that respondents engaged in moderate to high levels of information-seeking behaviour. In the context of the eight-stage information-seeking model, it was observed that the information behavior associated with evaluating differences across information sources had the highest average information seeking score for both genders, which involved assessing differences in information and then validating its accuracy. According to the Ellis model, men and women behave similarly while seeking information. However, with the exception of behaviours related to tracking or following the flow of information about amulets, the research indicates that men show more passion for engaging with information on amulets compared to women.

Table 10 shows that amulet collectors of all ages often have average information-seeking behaviours regarding amulets, with significant differences at the 0.05 level. This verifies H3’s findings. The age range of 30 years and older has the highest level of overall information-seeking behaviour (31-40, ˉx=3.62; 41-50, ˉx=3.61; over 50 years, ˉx=3.58), as opposed to the group under 30 years of age, which has moderate information-seeking behaviour (21 or less, ˉx=3.07; 21-30, ˉx=3.28). The study discovered differences in each step of data extraction when comparing users of amulet data of various ages. Ellis’s information-seeking behavior model indicates that users under 21 showed the lowest average information-seeking behavior compared to other demographic groups in terms of starting a search, chaining, exploring, differentiating, extracting, and verifying data.

When searching for information about amulets, users in different careers exhibit a moderate level of information-seeking behaviour. Examining the occupational groups of information users, we found that professionals such as doctors, nurses, soldiers, and police exhibited a strong inclination to seek information about amulets ( ˉx=3.77), followed by those in business or trade-related professions ( ˉx=3.55). However, information-seeking behaviour in the academic group is at a moderate level, with an average score of 3.08, distinguishing it from other occupational categories. According to the results presented in Table 11, users across various professional categories often compare the information they obtain from amulets to identify similarities or differences, thereby verifying the accuracy of the gathered information. The professional group had an average of 4.17, the business entrepreneur group had an average of 4.10, and the academic group had an average of 3.60. Ellis’s information-seeking behaviour at each stage differed from that of other occupational groups. Academics exhibit the least information-seeking behaviour at every stage compared to other occupational groups.

Differences in information-seeking behaviours among information users with different occupational characteristics

When looking up information on amulets, users from different disciplines of study exhibit varying average behaviours. The research findings indicated statistical significance at the 0.05 level. Those in science and technology were more likely to look up information about amulets ( ˉx=3.61) than those in the humanities and social sciences ( ˉx=3.33). The information-seeking behaviour model revealed statistical differences between users from various fields of study. The results include actions such as initiating the search for information, chaining the data, monitoring, extracting, and concluding the search for information about amulets. Participants in science and technology reported a greater desire to seek information than those in the arts and social sciences. As shown in Table 12, the study’s findings support H3: Different academic backgrounds result in different information-seeking behaviours among users.

5.5. Relationship Between Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Information-Seeking Behaviour

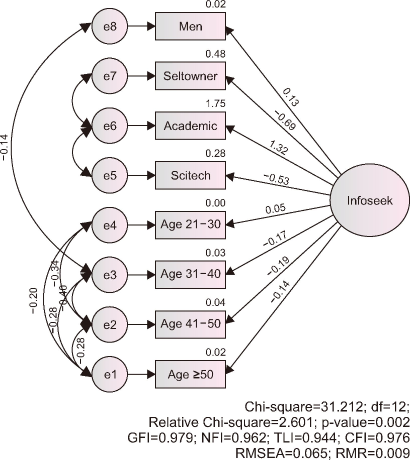

H4 suggests that occupation and academic discipline have a more significant positive impact on information-seeking behaviour regarding amulets than do gender and age. Structural equations have been utilized to investigate the hypotheses regarding the impact of individual traits on the behaviour of seeking information about amulets. The findings of the investigation are presented in Fig. 1.

The structural model diagram. GFI, goodness-of-fit-index; NFI, normed fit index; TLI, Turker-Lewis index; CFI, comparative fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; RMR, root mean square residual.

The diagram illustrates the influence of the personal characteristics of amulet collectors on their information-seeking behaviour through eight observable variables in the structural model. It can explain the effects of individual characteristics. The research results demonstrate strong consistency when evaluating different criteria and conditions of structural equations. The findings from the structural equation analysis reveal that personal factors, including gender, age, job traits, and academic background, can account for up to 37% of the variance in information-seeking behaviour. Furthermore, analyzing the coefficient of variation reveals that variables associated with the men gender, ages ranging from 21 to 30 years, and occupational attributes of academics show a positive effect. However, for people aged 31 and above, having only a rudimentary understanding of science and technology has a negative effect. The occupational factor associated with being an academic has the highest impact, with an effect size of 1.32, followed by the occupational factor associated with being an entrepreneur, with an effect size of -0.69. Therefore, the study results support H4, which asserts that the professional characteristics of scholars who collect amulets positively influence their amulet-seeking behavior more than other personal characteristics. However, the study rejects the notion that the field of amulet collectors has a negative influence on the behavior of seeking amulet information.

6. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

In the past, people created amulets to honour Buddhist teachings, promoting morale and motivating the wearer. However, in many cases, there are legends that describe stories of holiness or miracles involving amulets, leading people to form beliefs regarding the amulets’ abilities. As a result, amulets were converted into products, with people increasingly willing to pay for their spiritual benefits. A business relationship has developed by connecting amulet production to the market system, making amulets marketable commodities with economic value. Like other commodities, amulets are marketed through an organised framework that encompasses production, marketing, public relations, and speculation. To make informed selections, buyers purchasing amulets should learn more about them.

The findings of this study indicate that individuals with varied characteristics exhibit different behaviours when seeking and selecting sources of information. Adolescents are more likely than adults to engage in online activities with the intention of renting or buying religious amulets. This indicates a society heavily reliant on technology, despite embracing traditional elements such as beliefs, superstitions, magic, amulets, and talismans. Young individuals, in particular, experience a sense of uneasiness and seek amulets or sacred objects to swiftly elevate their spirits or assist them in accomplishing their objectives. As a result, they rely on the power of these items to promote success and rapid wealth accumulation. Hence, contemporary amulet designs frequently symbolise attributes of rapid and secure wealth accumulation and upward mobility, catering to the modern desire for swift achievement, akin to the speed of the Internet. The findings of this investigation align with prior research conducted by Chanchai et al. (2023), and Kalchankit and Taiphapoon (2016), which indicate that those who engage in the worship of diverse amulets do so with the belief that it will enhance their chances of achieving success in their professional or academic pursuits.

Another supporting factor is the relatively high pricing of sought-after amulets, consistent with Chantanee (2016)’s research that analyzed amulet prices. Her research revealed a price range for amulets from 10 dollars to millions of dollars. As a result, amulet purchasing behaviour depends on personal characteristics such as age or income, which must be sufficient to purchase amulets. For these reasons, young people may be less interested in researching information before purchasing amulets. This contrasts with the purchasing goals of professional groups such as nurses, police officers, and soldiers. Research has revealed that this particular community of amulet collectors has a higher inclination than other professional groups to gather information before acquiring high-value amulets. This behaviour stems from their strong belief in the efficacy and attributes associated with particular types of amulets. This group of amulet collectors frequently possesses religious artefacts that serve as safeguards against harm or ensure the security of their lives and possessions. In contrast, individuals in the business sector actively pursue religious items with the explicit goal of boosting sales and fostering a sense of confidence. The findings of this research corroborate those of Keawimol (2015), who discovered that individuals in the business sector intend to acquire amulets for the purpose of collecting them and expecting enhanced trading outcomes or profits in the future.

Furthermore, many collectors of amulets rely on various sources of information, particularly experts in the field who can categorise and verify the genuineness of amulets, to obtain the desired knowledge or determine the specific market value of the amulets. Individuals younger than 21 years old tend to use online social networks as their primary means of acquiring information rather than other sources. This younger generation often demonstrates advanced proficiency in using digital technologies for information retrieval. However, the use of Internet social networks to gather information on amulets has transformed the traditional method of in-person meetings into virtual interactions. This indicates that amulet collectors still depend on personal sources for amulet-related information. This is consistent with the findings of Kalchankit and Taiphapoon (2016)’s research, which demonstrated that individuals who have a passion for collecting lucky gemstones often seek information through new media platforms, predominantly Internet-based social networks. Therefore, it is noteworthy that there has been a surge in the use of online social networks as sources of knowledge. The rise of online groups centered around lovers and collectors with a shared interest in holy artefacts is responsible for this phenomenon. Platforms such as Facebook provide convenience, allowing anyone interested in increasing their knowledge about amulets to easily access relevant information without distance or time limitations. It is fascinating that amulet collectors searching for information about religious items often neglect traditional sources such as books and journal articles. This contrasts with the study by Tosomboon and Rungkhunakorn (2021), which discovered that amulet experts primarily acquire knowledge through books or journals, and they also actively gather information using online social networks.

While amulet collectors’ beliefs and faith in Buddhism, along with the attributes of amulets, may appear superstitious and defy scientific explanation, individuals still require psychological connections despite significant advancements in digital technology. They express these connections through behaviors that vary based on their unique traits. Fans of amulets actively seek knowledge about these objects to support collectors’ ideas and provide explanations or clarifications to others. Thus, it pertains to the psychological and anthropological aspects of human behavior. We can use the findings of this study to advance information services and develop a semantic search system for amulets that aligns with the information-seeking patterns of amulet collectors. An ideal system should facilitate communication among those interested in religion, helping them interact with one another or seek guidance from professionals in the field. The system should also enable amulet collectors to share information or knowledge. Additionally, there must be tools available to examine the attributes of religious artifacts, as each object possesses distinct attributes and carries a unique price. Those interested in renting or buying religious amulets or objects will find this information useful. This material will provide them with fundamental information. Alternatively, it can serve as a platform or learning hub for scholarly endeavors, facilitating the future dissemination of knowledge about amulets among collectors and enthusiasts.

REFERENCES

, , , (2022) The influence of sociodemographic behavioural variables on health-seeking behaviour and the utilisation of public and private hospitals in Ghana International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 42, 455-472 https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-03-2021-0068.

Bangkok Business Media (2023) The government supports religious and cultural tourism, recommends using discretion when worshipping sacred objects https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/politics/1084069

(1989) The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface Online Review, 13, 407-424 https://doi.org/10.1108/eb024320.

, , (2023) Behavior and belief attiudes in sacred stone of women in Bangkok Santapol College Academic Journal, 9, 196-204 https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/scaj/article/view/264828.

, , (2000) Information seeking on the web: An integrated model of browsing and searching First Monday, 5(2) https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v5i2.729.

, (1997) Modelling the information seeking patterns of engineers and research scientists in an industrial environment Journal of Documentation, 53, 384-403 https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007204.

(2021) Influence of demographic factors on information-seeking behaviour of medical doctors in teaching hospitals in Nigeria Library Philosophy and Practice, 6220 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/6220.

, (2015) The effect of socio-demographic characteristics on the information-seeking behaviors of police officers Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38, 350-365 https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2014-0132.

(2017) Business and marketing models of Buddhist commercialization in Buddhist institutions Journal of Buddhist Studies Chulalongkorn University, 24, 57-79 https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jbscu/article/view/156677.

, , (2008) The 'information search process' revisited: Is the model still useful? Information Research, 13, 355 http://InformationR.net/ir/13-4/paper355.html.

, , , (2015) Music information seeking behaviour as motivator for musical creativity: Conceptual analysis and literature review Journal of Documentation, 71, 1070-1093 https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2014-0139.

(2011) Amulets and the commercialization of Thai Buddhism https://cupblog.org/2011/11/30/justin-mcdaniel-amulets-and-the-commercialization-of-thai-buddhism/

, , , (2000) The impact of the internet on information seeking in the media Aslib Proceedings, 52, 98-114 https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007004.

, (2013) Information seeking behaviour of astronomy/astrophysics scientists Aslib Proceedings, 65, 109-142 https://doi.org/10.1108/00012531311313961.

(2006) (master's thesis) Bangkok, Thailand: Silpakorn University Buddha Panich: Amulets image, https://sure.su.ac.th/xmlui/handle/123456789/1518

, , (2020) Buddhist commercialization in Buddhist institutions Journal of MCU Nakhondhat, 7, 424-439 https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JMND/article/view/248312.

The Standard Wealth (2021) Amulets with an astonishing value of faith https://thestandard.co/thai-buddhist-amulets-of-high-value/

(1999) Models in information behaviour research Journal of Documentation, 55, 249-270 https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007145.