1. INTRODUCTION

An organisation can be defined as a group of people who collectively undertake certain actions such as planning, arranging, coordination, structuring, administration, organizing, management, logistics, and the like, in order to achieve a pre-determined goal. An online business dictionary (www.businessdictionary.com) affirms that the word organisation is synonymous with words such as: firm, business, company, institution, establishment, corporation, etc. Hence, an organisation can be a business or a government department. In other words, organisations can be private or public; small, medium or large-scale; profit or non-profit oriented. They can also specialize in different endeavours such as manufacturing, repackaging, sales, services, and so on. Library and information centres, as distinct departments of government and non-government institutions, are prime examples of service providing organisations. They are public-service kind of institutions and are comprised of men and women of defined and related knowledge backgrounds, who collectively pursue a goal of providing information services to particular groups of people at different places and times.

In view of this, library and information centres are not completely different from other organisations. All organisations require management to succeed. Management as defined by several researchers and scholars can be summarized as the judicious use of means to accomplish an end (Stroh, Northcraft, & Neale, 2002). Right from the late eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century, the importance of management as a factor that determines organisational success has all along been buttressed (Robinson, 2005; Witzel, 2003). Several experiments were conducted by different people such as Frederick Taylor, Henri Fayol, Max Weber, Elton Mayo, Abraham Maslow, Douglas McGregor, among others. These theorists are today regarded as the forerunners of management scholarship. The results of their experiments and/or experiences at the earliest industries and companies in Europe and America led to the postulations of several management principles, also called theories or philosophies. However, popular among the several management principles postulated by the management forerunners is Henri Fayol’s ‘14 principles of management’ (Witzel, 2003).

The popularity and wide adoption of Henri Fayol’s management principles led to his being nicknamed the father of modern management (Witzel, 2003; Wren, Bedeian, & Breeze, 2002). Henri Fayol was a French engineer who lived from 1841-1925. Early in life, at about 19 years of age, he followed after his father’s engineering profession. He enrolled and graduated from a mining academy in 1860 and took up a mining engineering job in a French mining company. By 1888, Fayol became the director of the company which he later turned around to become the country’s biggest industrial manufacturer for iron and steel with over 10,000 staff in 1900. Fayol directed the affairs of this mining company until 1918 (Fayol, 1930; Pugh & Hickson, 2007). As a sequel to his wealth of experience and series of research endeavours, in 1916 Henri Fayol published the ‘14 principles of management’ which later appeared in his boo Administration Industrielle et Générale in 1917 (Faylol, 1917; 1930).

Management researchers over the years opine that the ‘14 principles of management’ propounded by Fayol is what metamorphosed into present-day management and administration, especially after 1949 when his book was translated from French to English, as General and Industrial Administration (Rodrigues, 2001; Fayol, 1949; Wren, Bedeian, & Breeze, 2002). It is believed also that every organisation on the globe today is influenced by Fayol’s principles of management given their applicability to burgeoning administrative formation without which there will be no organisation - as a group of people pursuing a collective goal. It is on this premise, therefore, that this paper is set to critically analyse the implications of Fayol’s 14 principles of management as culled from his 1949 publication (Fayol, 1949) with a view to highlighting their implications to the administration of library and information centres.

2. HENRY FAYOL’S 14 PRINCIPLES

2.1. Principle 1: Division of Work

Henry Fayol’s first principle for management states that staff perform better at work when they are assigned jobs according to their specialties. Hence, the division of work into smaller elements then becomes paramount. Therefore, specialisation is important as staff perform specific tasks not only at a single time but as a routine duty also. This is good to an extent. In library and information centres, there are such divisions of work. The Readers’ Services Department of the library (variously called User Services, Customer Services, Public Services, etc.) also divides its vast jobs into departments and units. Not only has this point been substantiated by other writers, it has also been proved to be applicable to Technical Services Departments (Aguolu & Aguolu, 2002; Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007). Fayol, no doubt, was accurate in his division of work principle in the sense that all jobs cannot be done together by all staff at the same time. Besides, efficiency and effectiveness of work are better achieved if one staff member is doing one thing at a time and another doing a different thing, but all leading to the same collective goal, at the same time. By this, work output can be increased at the end of a given time, especially in a complex organisation where different kinds of outputs altogether count for the general productivity of the organisation. Similarly, taking the cataloguing room of a library for instance, this principle also mandates that as one or two persons catalogue the books, another puts call numbers on them and another registers the titles as part of putting them together and readying them to move to the circulation wing. Even at that same time, another person at the circulation department may be creating space for their recording, shelving, and so forth. This is division of work and at the end of a day’s work, the amount of jobs executed for the day can be more meaningful than when every staff member is clustered for each of the job elements, one after another. By implication therefore, staff are assigned permanent duties and are made to report to that duty every day.

However, as observed in recent library practices, some proactive librarians act contrary to this as they, from time to time, reshuffle staff in a way that takes staff to fresh duties. Critically, the era of staff staying put in a particular office or duty-post is nowadays obsolete given the nature of contemporary society. This points to the fact that current management practices in libraries no longer support that method (Senge, 1990) and the reasons are clear. First, in the library and information science profession, the practice of specialisation in one area or aspect is not clearly defined in the first instance. For instance, this is evident in the professorial titles accorded to professors in the library and information science discipline. Many of them are not tied to any specific library and information science research area by their professorial title compared to what obtains in other science, engineering, and social science disciplines. Likewise, in the classroom, even at the research degree level, scholars’ research will often be informative of their possible areas of specialisation. But in practice (working in any library and information centre) it is rarely demonstrated. This is one internal point against the staff of libraries staying put in a specific job element for a long time and, for others, all through their service time. After all, teaching and learning in library and information science is generalized in content and scope and thus tends to produce men and women who can take up any job design in the practice of librarianship. So, library managers who allow staff to remain on a given job schedule on the excuse of specialisation may be dwindling job efficiency.

Secondly, judging from observations of the twenty-first century management style, generalisation of job design is advocated contrary to specialisation. Studies conducted in service rendering organisations show how managers in Western countries design jobs to suit all staff (Rodrigues, 2001). Thus, no single job design in today’s organisations requires core specialised staff to execute. Going by the evolution of machines, as we can also see in their introduction in library and information centres in the form of computers, automation, digitalization, and so forth, employment of staff is per their ability to use the machines to execute any job in the organisation. Yet, this does not mean that there is no division of work. There is still a division of work formulas but the modification is that staff are now managed to work in any division at any time because of the generalization of the work design. Take the OPAC system for example: there may not be a need to have staff job-tied to the cataloguing workroom because the OPAC system, as a typical job design platform, will allow any staff from any department to add and/or delete content on the library database. So, library and information centres managers should note the paradigm shift from division of work via specialisation to division of work via generalization.

2.2. Principle 2: Authority

This principle suggests the need for managers to have authority in order to command subordinates to perform jobs while being accountable for their actions. This is both formal and informal and is recommended for managers by Fayol. The formality is in the organisational expectations for the manager (his responsibilities), whereas the informality (the authority) can be linked to the manager’s freedom to command, instruct, appoint, direct, and ensure that his or her responsibilities are performed successfully. Again, the two are like checks and balances on the manager: he must not abuse power (authority). He must use it in tandem with the corresponding responsibility. Thus, Fayol believed that since a manager must be responsible for his duties, he should as well have authority backing him up to accomplish his duties. This is correct and quite crucial to organisational success.

In library and information centres, such is the case also. The Librarian-in-Charge is responsible for the affairs of the library and has corresponding authority to oversee it. Likewise, his or her deputies, departmental heads, and unit officers are accorded the same in their respective capacities. This makes the work flow smoothly. But by implication, the respective subordinates such as the assistant librarians, library officers, and library assistants or others, as the case may be, become bottled up in the one-man idea cum direction of the librarian. Unfortunately, most departmental heads become so conceited with their status, responsibility, and authority that they do not find it necessary to sometimes intermingle and relate with their staff. As a result, an icy relationship develops with attendant negative consequences, especially industrial disharmony and unwillingness of parties to share knowledge (Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000). This may not be in the interests of the library given the saying that “two ideas are better than one” (http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/).

More so, it is the junior staff members that interact with the practical jobs daily and are likely to regularly have something new in the field to teach the head. Obviously then, there is need for a managerial amendment on this principle. The emphasis should no longer be on power to command subordinates. Rather, it should be on encouragement of staff participation and motivation to take some initiatives. As the research by Blackburn and Rosen (1993) shows, award-winning organisations in the world apply participatory management and staff empowerment against the authority and responsibility principle. With this style, managers and their deputies act more as coordinators rather than dictators. Hence, library and information centres may not need the control-freak type of headship but preferably an orchestra-kind of leadership. Such leadership style will accommodate ideas, innovativeness, meaningful contributions, and freedom of expression from the junior staff, which research has shown to have positive contributions to the growth and success of an organisation (Blackburn & Rosen, 1993).

2.3. Principle 3: Discipline

This principle advocates for clearly-defined rules and regulations aimed at achieving good employee discipline and obedience. Fayol must have observed the natural human tendencies to lawlessness. He perceived the level of organisational disorder that may erupt if employees are not strictly guided by rules, norms, and regulations from management. This is true and has all along resulted in staff control in organisations. But in recent times, it has not been the best method to achieve long-term organisational order and goals. Management scholars have observed that peer group participation and other kinds of informal unions are now taking the control lead in organisations (Mintzberg, 1973). The individual differences amongst staff feared by Fayol, which no doubt led most organisations to break down because of a lack of formal and binding organisational rules or weak and poorly enforced codes of practice (Cavaleri & Obloj, 1993), are seemingly surmountable now through informal control systems. Workers unions and staff groups are getting stronger and stronger every day and have ethics guiding them. In organisations where they are allowed to thrive, management tends to have little or nothing to do towards staff control. As well, they can create resilient problems for managements who will not build a good working atmosphere with them. Yet, they have come to stay nowadays and become stronger every day rather than being suppressed by managements. Trade unionism by staff is, therefore, an element of the democratisation of industrial organisations and government establishments because it accommodates the opinions and interests of the worker in certain management decisions (Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000; Iwueke & Oparaku, 2011). Thus, the use of staff groups or unions is an informal control system. It can help organisations to maintain discipline. One hidden advantage managements that adopt this system have is that they save cost and time ab-initio allotted to managerial discipline.

Likewise, in library and information centres, this informal system of discipline can be adopted. Librarians are to become less formal in discipline rather than trying to enforce institutional rules and regulations at all cost. Proactive librarians can have fewer headaches from staff rumours, gossip, and other forms of attack that usually emanate in the process of enforcing institutional rules and regulations. They can achieve this by trying the system of allowing staff to form group(s) in their libraries. For instance, a vibrant junior staff group or senior staff group in a library can go a long way to infuse cooperation, unity, trust, commitment, and order among its members to the benefit of the library as an organisation. As long as the top library management gives them the free hand to exist, they will set up rules that can unite the library organisation more than it can divide it. Anecdotal observation shows that libraries whose staff members are happy with the level of love shown them via visits, celebrating/mourning with them, and so forth are such that have groups or unions in their library. This point is supported by some reports in some management textbooks which clearly suggest that industrial unions help to sustain discipline among their members and sustain industrial harmony (Imaga, 2001; Iwueke & Oparaku, 2011; Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000). So, while some managers quickly conclude erroneously that unions exist to fight management and make unnecessary demands, library and information managers should note that such groups can help the system to achieve order and maintain discipline. This out-weighs or counter-balances the fears of their existence.

2.4. Principle 4: Unity of Command

This principle states that employees should receive orders from and report directly to one boss only. This means that workers are required to be accountable to one immediate boss or superior only. Orders-cum-directives emanate from one source and no two persons give instructions to an employee at the same time to avoid conflict. And, no employee takes instructions from any other except from the one and only direct supervisor. This tends to be somehow vague. Fayol was not explicit to show if it means that only one person can give orders or whether two or more persons can give instructions/directives to employees but not at the same time. If the case is the former, this principle is rigid and needs modification, especially in consonance with current realities in many organisations.

Looking at the prevalent situations in most organisations nowadays where work is done in groups and teams, it simply suggests that each group will have a coordinator or supervisor that gives orders. And, this coordinator is not the sole or overall manager. Likewise, in some complex establishments, staff belonging to a given work team would likely take orders from various coordinators at a time. For instance, the head of a Finance Department can give instructions to staff relating to finance; the Electrical Department head can do the same to the staff also relating to power and vice-versa. Thus, in large and small organisations, it is not unusual for a staff member to receive instructions from superiors outside his/her immediate units/sections or departments (Nwachukwu, 1988). In a library, the officer in-charge of cataloguing can instruct the Porter not to allow visitors into the cataloguing workroom; the circulation head can at the same time tell the Porter to watch out for a particular library user at the exit point of the reading hall. These are two different orders from different departments. The Porter, by this, would not say that he cannot take orders from any of them save the Chief Librarian or that only one of them should instruct him and not the two. The Porter may not effectively watch out for the suspected user and at the same have his eyes on the cataloguing workroom wing. However, tact is required as he/she is not expected to flagrantly flout the directives of superiors. The point being stressed is that in modern libraries and information centres, it has become conventional for staff to take orders from multiple bosses even as the primary job is discharged (Agoulu & Aguolu, 2002; Ifidon, 1979).

2.5. Principle 5: Unity of Command

This principle proposes that there should be only one plan, one objective, and one head for each of the plans. Of course, organisations run on established objectives (Drucker, 1954). But, this should not be misinterpreted with departments and units who seemingly have their specific objectives. What Fayol meant is that an organisation will naturally have central objectives which need to be followed and as well departmental and unit goals which also need to be reached in order to meet the unified objective.

Library and information centres are established to collect and manage the universe of information sources and provide information services to their users. But also, there are other goals from departments and units, sometimes differing from each other. This is in line with the job specifications and peculiar work routines of each of the various sub-systems that make up the library (Edoka, 2000; Nnadozie, 2007). However, the activities of each department or unit are aimed at supporting the library’s central objective of providing information services to users. And for each of the departments to attain its goals, they set and implement multiple plans (not one plan). So Henri Fayol’s original proposal that one plan should be pursued by one head only is no longer tenable. For example, the Circulation Department of the library has to offer lending services and also register library users. Does it mean that it will have separate heads because of the different assignments involved? No; it is true that plans are different, and in this case, one is set for how to register users and the other strategizes how to lend out library materials to people and ensure that they return them, or be responsible for not returning them on time or at all. Yet, that does not call for a separation in the job in terms of headship. Rather, what library managers should insist on is that department goals and plans should be pursued in an orderly manner so that staff will not have to get a special head for each plan of group activity. This approach to management is already in place in most libraries in Africa where few hands are used to deliver multiple tasks due to shortages of staff (Ifidon, 1979 & 1985).

2.6. Principle 6: Subordination of Individual Interests to Organisation’s Interests

The interests of the organisation supersede every other interest of staff, individuals, or groups. Imperatively, employees must sacrifice all their personal interests for the good of the organisation. In other words, organisations should not tolerate any staff that are not committed to the organisation’s objectives and order even if it is to the detriment of personal and family interests. This is one hard way of pursuing organisational or corporate success. It may have worked before now, but it is not ideal any longer due to a series of reasons. First, Mayor (1933) and McGregor (1960) have shown that employees can do better at work when they are valued and shown a reasonable sense of belonging. Second, organisations are compliant to the inconsistency of change. They change their objectives as situations warrant and need their staff to adapt fast to the changes. And, one of the fastest ways to get staff to adapt and comply with organisational changes is to invest in the staff. Thus, staff training and retraining, which is at most times cost-effective for management, is not only an investment in the staff for the organisation to reap but also a commitment to staff personal development. During such training sessions, staff enjoy several benefits such as job security, payment of salaries, full sponsorship, and other allowances that makes staff happy and motivated to put in their best when they return from the training programme.

The application of this principle should not be frustrated in library and information centres. Library managers and administrators must learn to make staff work happily. Happy staff will always put in all their best at work. Ways of keeping staff motivated to work happily include, from time to time, showing a commitment to staff both formally and informally. Formal commitments can come from sponsoring staff to further training, short development courses, seminars, and conferences. Some informal commitments include holiday support packages for staff, open and regular communication, and flexibility to staff personal requests. Library managers and administrators also use these formal and informal incentives to show their staff a sense of belonging, thereby making them more productive (Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007). For instance, a staff member permitted to leave office early to pick up her children from school will be glad and, more often than not, reciprocate by a commitment to work during the periods she will be at work. On the contrary, a member that is not permitted to attend to such personal needs and is regimented to the opening and closing hours of work at the library may sit back in his office all day achieving nothing. If a psychological test is conducted on this case, the result may likely show that the latter staff member achieved nothing in the office, not primarily because he wanted to pay back the manager by not working, but more because he was not able to concentrate at work and even when he tried he could not focus because of where his mind was; this is especially so if the family need for which the excuse is denied is crucial. Productive library administrators ensure that an environment is created for staff to have a sense of appreciation, especially when they have some personal needs. Staff with such a sense of appreciation or recognition tend to put in their best in the discharge of their work and pursuit of the library’s corporate goals (Aguolu & Aguolu, 2002). Thus, while it was held before that staff should give up their interests for the organisation, now the reverse is the case. This means that organisations commit itself to the interest of the staff so that they can be more productive and committed to the objectives of the organisation.

2.7. Principle 7: Remuneration

Payment of staff salaries should be as deserved. The salary should be reasonable to both staff and management and neither party should be short-changed. The salary of every staff member must be justifiable. A supervisor should receive more pay than line staff. Thus, whosever management appoints to be supervisor takes more than the subordinates by virtue of his or her responsibilities. It does not really matter whether a subordinate works harder and is more productive than the supervisor. As long as management does not promote the subordinate he continues to receive lesser pay to what his boss gets even as he works more than his boss. The above generally encapsulates Fayol’s position on remuneration.

However, this approach to the administration of the reward system is gradually giving way in contemporary library management practice. There is a noticeable modification in the application of this principle as it is arbitrary in nature (Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000). It is quite agreed that it will be inappropriate for a subordinate to receive more pay than his boss. So, management researchers have complemented Fayol’s notion with a new modifications arguing that this system of remuneration discourages hard work and productivity (Cascio, 1987). As a result, the “performance based pay system” recommended by Wallace and Fay (1988) is what is used nowadays. This pay system supports the idea that organisations should design a performance scale with which staff should be evaluated. Imperatively, productive staff get promoted and take more salary than non-productive staff. In a way also, this was Taylor’s (1911) idea that has just re-surfaced. Taylor’s idea supports hard work and extra commitment from the staff. His notion was that the more output from an employee, the more pay he receives. So, with this modification, every staff member receives a salary based on his or her measured output.

In present day library and information centres, this productivity measurement scale is adopted. In fact, the performance-based pay system is almost the norm everywhere. The only problem with some libraries and other information-related organisations is that they do not publish and/or orientate their staff on the measurement scaling or promotion criteria. Staff need to understand the criteria and have free access to the document. More so, library managers should as a matter of morality be just in the productivity measurement. Most librarians discourage their hardworking staff or make them resign for another job as they usually envy some member’s speed of productivity and promotion. Some library managers and their deputies are in the habit of comparing the number of years a hardworking and productive staff member has spent on the job with the many years some lazy and unproductive staff have given on the same job as a reason for why the former should not rise faster or even above the latter. This point has been raised in some library science textbooks where non-adherence to the principles of the performance-based reward system has been faulted (Aguolu & Aguolu, 2002; Edoka, 2000). Library managers should, therefore, avoid sentiments and award promotions to whoever has worked for them as many times as their hard work qualifies them. This is crucial if a library must retain the best staff and survive in a highly competitive information environment.

2.8. Principle 8: Centralisation

This principle suggests that decision-making should be centralised. This means that decision-making and dishing-out of orders should come from the top management (central) to the middle management, where the decisions are converted into strategies and are interpreted for the line staff who execute them (decentralisation). This is still working in many organisations. Library and information centres also apply this principle. For instance, it is conventional for the Librarian-in-Charge to hold meetings with deputies and/or departmental heads to initiate broad policy guidelines while the deputies and departmental heads take management decisions to their departments and units where they are finally executed and monitored (Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007). Nonetheless, management researchers have found another system which is working for many western organisations. Blackburn and Rosen (1993) observe that successful organisations in the United States of America (USA) apply a group decision making and implementation system. This means that units and departments make decisions and strategize their implementation based on their task, control focus, and job specifics.

Bringing this to the library may nevertheless not be so clear, especially in the beginning. But if it can be tried, it means that library departments will be empowered to meet weekly or monthly, and to make decisions as relating to their department, design their jobs, and draw their roster and schedule of duty. Later on, the decisions and plans of the department will be forwarded to the Librarian-in-Charge for immediate input and approval. Such a system of decision making allows for innovativeness and broad thinking among staff of all levels and also allows the Librarian to be less burdened with the library’s daily complaints. As well, librarians can have time to attend the numerous institutions’ meetings which they are statutory members of by reason of their position. However, it should be noted that the group decision making system cannot survive in bureaucracy—a system where mails are delayed for long. The Librarian must be committed to treating mail every day. In his absence, he should appoint someone to deputize him. This is because the work group decision-making system requires management to approve or make input to the group’s decision before they can commence work. Take for instance where the Digital Library Department of a library has met and taken a decision to be closed to users for three days to enable them to embed an anti-pornography firewall on their server system in order to save it from unauthorized downloads that may crash the server. The decision mail reached the Librarian’s desk and for many days it was yet to be treated. Although oral communication to the Librarian can be faster in this case, in a management system where records are necessary for actions, the Librarian’s delay in treating the mail would not do any good to the group’s decision. So, while the system is good, it requires promptness on actions from both management and staff. Thus, Fayol’s ‘principle of centralisation’ is like a trickle-down decision flow, routing decisions from top to the bottom. But the work group decision system suggested therein is a bottom-up movement, which allows the staff to initiate ideas and job specific decisions for the organisation.

2.9. Principle 9: Scalar Chain

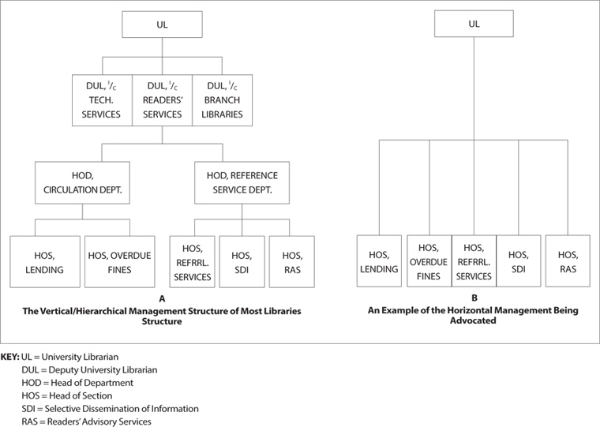

This principle is a product of the formal system of organisation. It is also known as the hierarchy principle. It asserts that communication in the organisation should be vertical only. It insists that a single uninterrupted chain of authority should exist in organisations. Horizontal communication is only allowed when the need arises and must be permitted by the manager. This vertical organisational and communication arrangement is the conventional practice in most library and information centres where orders and similar directives flow from the Librarian-in- Charge to the Deputy Librarians, to the Departmental Heads, and to the Unit or Sectional Heads, respectively (Edoka, 2000; Nnadozie, 2007). This is a four-layer hierarchy. It is neither twelve nor three layers, as Braham (1989) argues that a three-layer organisational hierarchy does better and faster than a twelve-layer hierarchy. Also, it has been shown in research that US-based organisations that practiced one-layer hierarchy systems recorded far better results than others that operated three-layer systems and above (Hinterhuber & Popp, 1992). Nowadays, a horizontal or flat management hierarchy system is advocated against the vertical order canvassed by Henri Fayol. The argument is that the former helps organisations to take decisions and implement them faster without unnecessary bottlenecks, contrary to what is observed in the later. Should this be applied in library and information centres, the implication is that the relatively vertical hierarchy order in most libraries should be displaced with the flat or horizontal hierarchy system. Figure 1 is a comparative illustration of a typical vertical organisational structure and the horizontal alternative being proposed.

Based on the above illustration, coupled with the new management findings that a horizontal organisational hierarchy allows for faster decision making and implementation than the vertical order system, library and information centres may have to operate a horizontal hierarchy system (Fig. 1 Diagram B) henceforth. The present system of having divisional heads, departmental heads, and in some cases, unit or sectional heads also (Fig. 1 Diagram A), may have to give way for a flat order where it will only be the Librarian-in-Charge and, most directly, the unit/sectional heads (as per specific job element or focus). However, this may not be welcomed by librarians in some institutions and countries where the deputy and departmental heads positions attract office allowances and other appurtenances. Yet, we must be realistic; such ladders on the management chart may not be helpful for library organisation in the nearest future. But, this one thing can be done also: break down the vertical order (Diagram A) into a flat order (Diagram B), increase the Sections/Units based on job specifics and call them Departments (which is more conventional), and redistribute the office heads in the initial vertical order to head the departments. This way, the fear of losing office/headship allowances and other benefits is averted. The beauty of the horizontal organization being advocated lies in its adaptability to the peculiar needs of both small and large libraries (Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007). Besides, most library staff are at home with its flexibility bearing in mind that positions attained by promotion (such as Senior Librarian or Deputy Librarian positions), are not in any way to be affected in the horizontal system. Hence, Mr. A can be an Assistant Librarian by grade and heads a department while Ms. B can be a Deputy Librarian by grade, also heading a department. Both of them report directly to the Librarian-in-Chief. Yet, the grade level and rank status of both is not the same and cannot be the same just on the grounds that both of them are departmental heads. Of course, there will be no problem with the remuneration system also as it is based on performance scale (grade level) and not on positional status (the headship privilege). The only thing that may be the same in this case is the headship allowance, if it is across the board for all staff grades. But, the normal annual salary (remuneration) due for each departmental head is purely determined according to grade levels and as such will vary among the heads.

2.10. Principle 10: Order

This is another formal organisational control system which has been interpreted in different ways. Some see it as the rule of giving every material its right position in the organisation and others think that it means assigning the right job to the right employee (Rodrigues, 2001). Whichever is the case, library and information centres must keep every information material in the right place and as well assign staff to jobs that suit them. A Library Assistant is not expected to handle the office and responsibilities of a Senior Librarian. This is because, among other things, their qualifications, job schedule, and remunerations are clearly different (Ifidon, 1985; Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007). However, buttressing more on the first suggested meaning of Henri Fayol’s ‘principle of order,’ it is true that information resources in the library should be kept in the right place. Here, what makes a place right is the ease of access and use it avails the users. Let us take the location of offices for example. In a library complex of two or three floors, the office of Librarian has no convenience in being located at any of the offices at the upper floors. Visitors to the Librarian’s office, who have nothing to do with the readings halls and other departments, have no business passing through or across them before they can access the Librarian’s office. The Librarian’s office should be located on the ground floor where visitors and users can access it easily. Likewise, the porter stand should be accessible to users immediately when they enter the library. This is the prevailing practice in the Nigerian university system in West Africa as most of the library briefs are in line with this proposal (Ifidon, 1985; Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007; Ononogbo, 2008). Users do not have to walk to one point to keep their bags and down to another point before they can enter the library.

In fact, if library and information centres must comply with this principle of order, it must be looked at from a more holistic point of view. For instance, taking a look at the present structure of offices and demarcations of most library buildings in Nigeria, the principle of order is practically compromised. This is in spite of the good suggestions in the available librarians’ and architects’ briefs for the construction of library buildings (Ifidon, 1985; Ifidon & Ifidon, 2007; Ononogbo, 2008). In a library that wants to infuse order right from the design of its work environment, the transparent partitioning system, as seen in Banks, is ideal for adoption. Nowadays, organisations operate the open office system. An open office is that in which there is little or no privacy as the only partition between offices could be just transparent glass walls. In some cases, dwarf walls or wooden boards are used. The major benefit of this arrangement is that it enhances transparency and ventilation (Idih, Njoku, & Idih, 2011). Staff can see themselves from their offices. The users can see them as well too.

The Readers’ Services Departments of the library and their officers are the most likely to adopt this system of office sitting/demarcation. It allows the head of the department to see his staff and users also while they too see them. In this case, there will hardly be room for staff that do unethical things in the library such as sleeping, eating, and gossiping in the office. Likewise, users will be more cautious while in the library because staff from various offices can be watching them. In fact, the transparent partitioning of library staff offices will intuitively drive staff to work and not to relax or chat away during official hours. However, this transparent partitioning system should not be open to users in the case of Technical Departments. But within the technical departments, the offices should be transparent too so that staff can see themselves. These are some important elements of order which could be modified to suit the peculiar needs of libraries.

2.11. Principle 11: Equity

Another word for equity is fairness. Henri Fayol suggested that managers should be fair to their staff. But the fairness required, probably, is such that must make staff to comply with principle No. 6 - subordination of individual interests to organisational interests – which does not lead to desired productivity in organisations nowadays. As suggested earlier under principle No. 6 in this paper, the system of organisation that flourishes in today’s society is such that accommodates staff and owns them up, as it were. Such organisations make staff feel at home, share a portion of profits with staff, communicate with staff, remain open to staff, share staff feelings, and identify with staff personal/family challenges. This is the type of organisation that succeeds these days. Managers of library and information centres can apply these strategies in their relationships with members of staff. Where they do, they will avoid all forms of partiality, treat all staff equally, deny no staff promotions, and encourage weak staff to shape up. More so, they advise staff regularly on how to grow on the job, mentor staff, avoid favouritism, build up an unbiased attitude, and disallow gossip. Staff of the library are rewarded or punished based strictly on their commitment, faithfulness, and productivity and not on either friendship or filial relationships (Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000). This means that openness to all and even- handedness are integral parts of the key to attaining equity in organisations. So, library managers should rather address issues relating to staff before them and not at their backs. In all, impartiality is the kernel of this principle. As a result, it must be upheld by library managers not only in the interests of the library as an organisation, but also for their own good since observation has shown that impartial managers are respected and appreciated by their staff.

2.12. Principle 12: Stability of Personnel Tenure

In this principle, Fayol expresses the need to recruit the right staff and train them on the job with a hope to retain them for long. The basis of this principle is the belief that such staff with a secured tenure will put back into the organisation the knowledge and experience which they may have garnered in the course of working for the organisation. This, however, is considered an old-fashioned way of approaching management. Contemporary management is suggesting the recruitment of staff that are already-made with experience and with the right qualifications. Some organisations have gone further to downsize staff recruited in the old system because of their unwillingness to adapt to new ways of performing jobs in the organisation. As a matter of fact, new generation organisations are not merely keen in recruiting men and women whom they will invest much in from the start in order to get them working for the organisation. However, they are willing to spend on staff members that already have high success profiles and experience so that they can develop the organisation all the more. So, this is the era of recruiting the best qualified staff. The idea is that work can be very productive from the start and afterwards the staff can be trained to improve on what they already know how to do. This is one side of the principle and library and information centres managers should take note of it.

Another angle of Fayol’s ‘principle of stability of tenure’ is that staff should be retained for as long as possible, sometimes up to retirement. But, this is not the order of the day in recent times, as mobility of labour is becoming the culture of many workers. For one, workers believe in having several opportunities—that new jobs can offer such things as better pay, job satisfaction, promotions, job security, societal recognition, and others. But this is not healthy forlibrary and information centres. Brain drain is a factor that should be avoided. In fact, library and information centres should hold firm on Fayol’s principle here. Staff should be developed via on the job training, seminars, conferences, mentoring, and further studies. Organisational culture is not always easy to transmit and retain (Shein, 1984) let alone a system to change workers often. The majority of the new workers coming are often from another organisation with a different culture. So, managers of library and information centres should retain Fayol’s ‘principle of stability of personnel tenure’ but must avoid recruiting into the library men and women who will not be productive to the system until they are trained. An element of this is noticeable in the head-hunting and recruitment of subject-specialists by authorities of special libraries. Although this calibre of staff may be new when they report or resume, they have had previous exposure and experience in the public or private sectors (Nnadozie, 2007). When staff are recruited from other establishments, the direct and indirect costs involved in training staff upon employment should therefore be avoided. This, however, does not eliminate the need for on the job mentoring essential for both new and old staff.

2.13. Principle 13: Initiative

A good manager must be one who can be creative to initiate new ideas and also be able to implement them. Fayol was direct to managers at this point. He understood the importance of good ideas to the growth and success of organisations. But, on the contrary, he did not foresee the situation of today where staff are becoming the idea-banks of organisations. This has been observed in Western countries where group problem-solving systems are patronised against dependence on top level management as the problem-solving point (Magjuka, 1991 & 1992). Moreover, Mintzberg’s study in his PhD research (Robinson, 2005) confirmed that managers of these days seem not to be very good in initiating and implementing ideas as they are often preoccupied with so many other related and unrelated commitments that, in the end, leave them running after “work current, specific, well-defined and non-routine” activities. So, it is advisable for managers to empower their staff and give them the level playing ground required to initiate and implement new ideas.

In library and information centres, the almost non-existence of new ideas among librarians (especially in developing countries) has made library organisation seem uncreative, stagnant, and old-fashioned. This is the reason why their library customers, especially adolescents and young adults, are resorting to the Internet, since there is nothing new in the library. Whereas the Internet and its accompanying technologies offer a lot of platforms for proactive librarians to work with and retain their customers, a good number of library staff and their managers are rather not systematic and reflective planners. It may be that staff are waiting for the Librarian for initiatives and the Librarians-in-Charge, as managers, are preoccupied with numerous other things. This should not continue if the library organisation hopes to avoid decline and liquidation (Ohadinma & Uwaoma, 2000). Administrators and managers of library and information centres therefore should imbue their subordinates with the confidence to create and develop new ideas, as well as to implement them. Rewards and encouragements should be there for creative and/or innovative staff members so that generation of ideas can become competitive to the glory of the management and for the good of the organisation as a collective body.

2.14. Principle 14: Esprit de Corps

This is a French phrase which means enthusiasm and devotion among a group of people. Fayol is of the view that organisations should enforce and also maintain high morale and unity among their staff. This is imperative as the existence of an organisation is a result of the coming together of men and women under a collective interest. Thus, understanding, love for each other, unity, peace, and common determination is paramount to their success. The saying that united we stand, divided we fall is equally applicable in libraries and information centres. In the same manner, managers of library and information centres must ensure that the library organisation is characterized by staff unity and co-operation. This however does not mean that some staff members will not disagree or quarrel. It is natural with some human beings to quarrel once in a while. But library managers must be strategists in such cases to ensure that such misunderstandings amongst staff do not affect common goals of the library organisation.

3. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper has critically analysed the ‘14 principles of management’ proposed by Henri Fayol (Fayol, 1949). Some of the principles have been redefined and re-interpreted in recent management research to become better and more effective to organisations in their application. Yet a few others have remained as Fayol postulated them and are still widely adopted in the management of today’s organisations. Generally, all organisations are similar in some ways in the context of management as a practice. The issue of categorization of organisations, whether profit or non-profit, into manufacturing, marketing, sales, or services as products, does not demean the need for management in all types of organisation. A library and information centre is not different and therefore should also be treated as a business organisation. As a sequel to this, this paper has presented a modification or adaptation of each of Fayol’s 14 principles meant to guide managers of library and information centres. The principles are borne out of discourse on Fayol’s ‘14 principles of management.’ The new modified principles are comparatively presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fayol’s 14 Principles and their Implication in Today’s Library and Information Centres (LICs)

This paper therefore recommends the application of these principles to library administration. More so, research surveys can be conducted on case study bases to show the level of application of Fayol’s principles or similar principles in library and information centres. As a matter of fact, research into library management practices and methods should be encouraged. There are several management methods and approaches prevailing in contemporary society and only research can present a reliable picture of what the situation is in library and information centres. So, further research is not only needed to reveal management practices in library and information centres but also to identify contemporary management methods which can be adopted by library managers for the day-to-day administration of library organisation.