1. INTRODUCTION

In the last few years, a new type of social media has emerged: social live streaming services (SLSSs). Here, every user has the opportunity to produce and to broadcast his or her program in real time. In contrast to other social media, social live streaming services are synchronous, which means that all user activities happen at the same time.

When the social live streaming service YouNow became more popular during the last year, negative publicity about the “dangerous” behavior of teenagers appeared on the news. Possible violations of personality rights and especially of privacy were reported. To get a more comprehensive and broader view of the information behavior on live streaming services and to start a new point for further research, this investigation focuses on the information behavior on YouNow. It is the first empirical analysis of information behavior concerning general live streaming platforms.

Describing and analyzing SLSSs and their users is a new and exciting research field in information science. What information production behaviors do users of live streaming platforms exhibit? And what information reception behaviors can we observe? What are the motives of using social live streaming services? In line with these questions we have prepared an online survey with YouNow users as participants. For studying the legal aspects of information production behavior an analysis of potential law infringements on YouNow streams from Germany and the U.S. by Honka et al. (2015) was added to the study.

2. RESEARCH BACKGROUND

SLSSs are social media platforms with the following characteristics:

-

• they are synchronous,

-

• they allow users to broadcast their own program in real-time,

-

• users employ their own mobile devices (e.g., smartphones, tablets) or their PCs and webcams for broadcasting,

-

• the audience is able to interact with the broadcasting users via chats, and

-

• the audience may reward the performers with, e.g., points, badges, or money.

We differentiate between two kinds of social live streaming services:

-

• general live streaming services (without any thematic limitation), e.g. YouNow, Twitter’s Periscope, Meerkat Streams, YouTube live, or IBM’s Ustream, and

-

• topic-specific live streaming services, e.g. Twitch (games), or Picarto (art).

One of the most widely used social live streaming services is the topic-specific streaming service Twitch (Gandolfi, 2016), which is mainly used for streaming video games and electronic sports (e-sports) events (Burroughs & Rama, 2015). There are already several investigations and studies about this platform, but only few scientific studies on general live streaming services. We could identify a general paper on YouNow (Stohr, Li, Wilk, Santini, & Effelsberg, 2015), an article on technical issues of such services (LeSure, 2015), one about ethical problems (Henning, 2015) and a study on possible law infringements of YouNow users while streaming (Honka, Frommelius, Mehlem, Tolles, & Fietkiewicz, 2015). Fietkiewicz, Lins, Baran, and Stock (2016) found out that especially users from Generation Y (“Millennials,” born between 1980 and 1996) and from Generation Z (born 1996 and later) utilize YouNow. Wilk, Wulffert, and Effelsberg (2015) analyzed the improving of video contributions; and, finally, Wilk, Zimmermann, and Effelsberg (2016) studied video upload protocols.

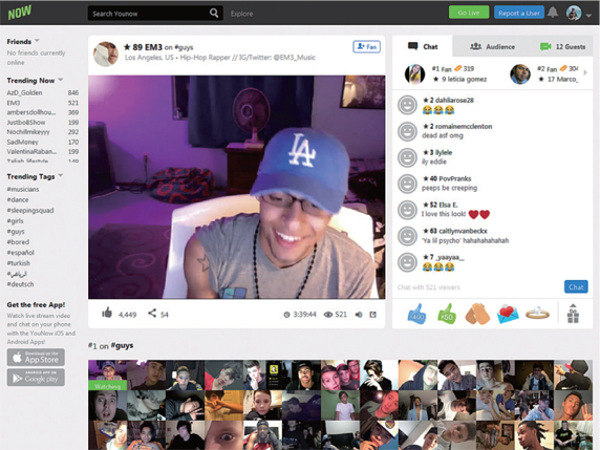

In this article, we apply research about information behavior on social media to general social live streaming services, using the example of YouNow as a case study (Fig. 1). YouNow’s mission statement highlights the convergence of social media and television as well as user interactions through real-time videos (YouNow, 2016). According to Adi Sideman, founder and CEO of YouNow, this information service broadcasts about 150,000 unique live streams daily (2015). Following Alexa, most users of YouNow come from the United States (24.3%), followed by people from Turkey (12.1%), Germany (8.4%), Mexico (7.6%), and Saudi Arabia (5.6%) (Monthly unique visitors in February, 2016). The average quota of viewers per broadcaster was (midyear 2015) 11 (Wilk, Zimmermann, & Effelsberg, 2016, p. 1), but in our experience the distribution of viewers is skewed: Few live streams have hundreds of viewers, while many streams were watched by less than ten people.

3. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR ON SOCIAL NETWORKING SERVICES

Following Savolainen (2007, p. 109), “information behavior” as well as “information practice” are “umbrella concepts” in information science. In contrast to Savolainen (2007), Case (2012), and other researchers, who link information behavior and information practice mainly to information seeking (e.g., Kumar & Rai, 2013; Majid & Rahmat, 2013), it is possible to broaden these concepts to all information-related human activities. Here, we are in line with Bates (2010) who defines “information behavior” as every human interaction with information. “Information behavior is … the term of art used in library and information science to refer to a sub-discipline that engages in a wide range of types of research conducted in order to understand the human relationship to information,” Bates (2010, p. 2381) concludes. Wilson (2000, p. 49) also defines “information behavior” in a rather broad way:

Information Behavior is the totality of human behavior in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information seeking, and information use. Thus, it includes face-to-face communication with others, as well as the passive reception of information as in, for example, watching TV advertisements, without any intention to act on the information given.

Fisher, Erdelez, and McKechnie (2005, p. xix) conceptualize information behavior “as including how people need, seek, manage, give, and use information in different contexts.” Robson and Robinson (2013, p. 169) propose an information behavior model that “takes into account not just the information seeker but also the communicator or information provider.” For Spink (2010, p. 4), information behavior is “a behavior that evolved in humans through adaption over a long millennium into a human ability, while also developing over a human lifetime.” The phylogeny of information behavior is the evolution of this behavior of the whole human tribe until today; the ontogeny is the development of the information behavior of an individual person (Stock & Stock, 2013, p. 465). We will work with this broad concept of “information behavior,” which covers all human information-related activities.

Information behavior depends on the context. For our case study, the context is found in social media or, to define more precisely, in social networking services (SNSs). Social media (or Web 2.0 media) allow users to act both as producers and as consumers (“prosumers”). Prosumers in social media are characterized by shared goals. They form virtual communities (Linde & Stock, 2011, pp. 259 ff.). One kind of social media are social networking services, which are platforms for self-presentation and communication with other members of the community (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). SNSs are either asynchronous (as for instance Facebook; Khoo, 2014, p. 81) or synchronous (as the social live streaming services). The main feature of social live streaming SNSs is the simultaneity of the communication, as all happens in real time.

The broadest term is “social media”; one of its narrower terms is (besides other social media as sharing services or weblogs) “social network services” (SNSs). “SNS” has two narrower terms: “asynchronous SNSs” (e.g., Facebook) and “synchronous SNSs.” Nowadays, social live streaming services (SLSSs) are the only kind of synchronous SNSs.

Social media has found its way into everyday life as well as into working life. It is clear that information behavior research addresses social media as a research object (Meier, 2015, p. 23). Khoo (2014, p. 90) concludes,

The rise of social media should herald a new era in information behavior research. Just as the rise of online databases and digital libraries sparked off a generation of research in online searching, so too social media should stimulate a new wave of research and theories focusing on other types of information behavior such as asking, answering and information integration. Research on information behavior on social media can be said to be in a nascent stage.

In line with Khoo (2014, p. 90), information behavior on social media includes information production and information reception behavior. In our study we emphasize information behavior on SLSSs.

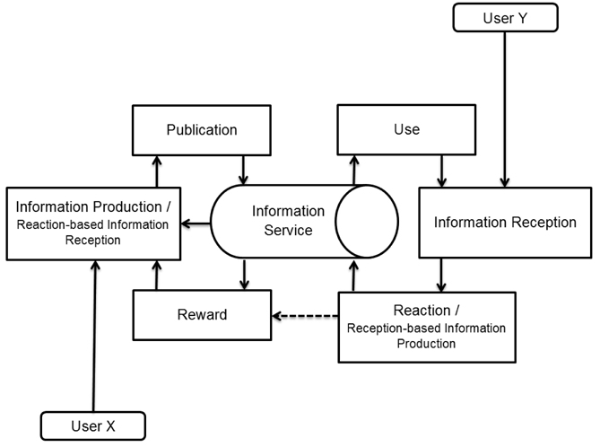

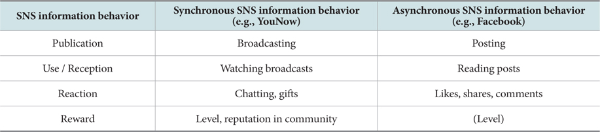

What are the differences in information behavior concerning synchronous and asynchronous SNSs? In contrast to other social media, information behavior on SNSs in general configures a complete cycle (Fig. 2). One user (in our figure it is user X) produces information and publishes it. In an asynchronous SNS like Facebook such a publication is a textual post, an image, or a video; in a synchronous SNS like YouNow it is a broadcast (Table 1). The information service is the platform that enables the communication between the information producer and the information recipient. Another user (user Y) utilizes the information service, searches for information, and receives the post or the broadcast. Information reception behavior in an asynchronous SNS will be reading the published posts; in a synchronous SNS this means watching broadcasts in real time. All SNSs allow the recipients to react to a published source, be it by a like, share, or comment on Facebook, or by chat, emoticons, and gifts on YouNow. One can consider the comments of user Y as a kind of information production, but (in contrast to the information production of user X) it is information production in consequence of information reception. Of course user X can or will realize the reactions of the audience. So she or he exhibits information reception behavior in consequence of her/his former information production behavior. Her or his further production behavior can depend on such reactions. The last step in the cycle is the reward for the information producer. This rewarding function is not adequately developed in asynchronous SNSs (although there are user levels on Facebook), but much elaborated in synchronous SNSs. On YouNow, the level of a performer plays an important role for her or his reputation in the community. The user earns virtual currency (“coins” on YouNow) by broadcasting and by receiving presents from other users. Such coins are needed to endow other performers. Additionally, YouNow offers the currency of “bars” to be bought with real money. The boundaries between reactions and rewards are sometimes blurred. For instance, a receiver, say user Y, “likes” a post on Facebook or presents a “heart” on YouNow, so this is Y’s reaction to X’s post or broadcast, but Y can think of it as a reward as well, and X can perceive it as a reward. From these theoretical considerations we derived the framework shown in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Here, our research questions arise. Using the example of YouNow, we want to know users’ information behaviors on social live streaming services. In this study, we are going to answer empirically three research questions (RQs), which all consist of three sub-questions:

(RQ 1) What information behavior do users of social live streaming services exhibit?

-

(RQ 1a) What activities do users practice on such information services?

-

(RQ 1b) What are the motives for this information behavior?

-

(RQ 1c) What influence does rewarding have on users’ motivation?

(RQ 2) What information production behavior can we observe on SLSSs?

-

(RQ 2a) Do performers prepare for their live streams?

-

(RQ 2b) How long are the live streams?

-

(RQ 2c) Do performers work with external music, images, and videos? Are there any legal concerns?

(RQ 3) What information reception behavior can we observe on SLSSs?

-

(RQ 3a) What kinds of broadcasts do users view?

-

(RQ 3b) Which age of performers do they prefer to view?

-

(RQ 3c) Do users link their live streaming accounts to other information services?

All research questions are focused on the current usage status of YouNow.

4. METHODS

To answer the research questions, we conducted two empirical investigations, namely an online survey and observations of live streams. Our first investigation is survey-based. It took place from June 3 until June 28, 2015 on Umfrageonline.com and had 123 YouNow users as participants. In the survey, the users were asked questions about YouNow, their behavior concerning YouNow, and the acceptance of the service in the community.

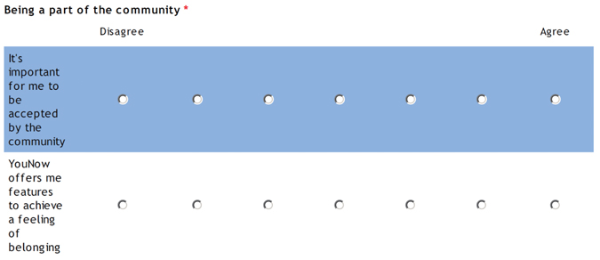

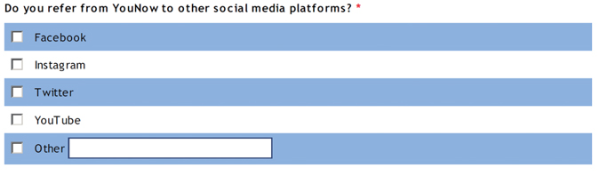

For the majority of the items we pre-formulated answers and defined a 7-point Likert-scale (from “disagree” via “neutral” to “agree”) (Likert, 1932). For instance, in order to answer RQ 1b (on motivations) we prepared for the item of “being part of the community” two statements (Fig. 3). The participants marked their attitude for every statement in one of the seven boxes. We consciously worked with an uneven number of attitudes, which includes a value for “neutral” in the middle. In our analysis, we summarized the values 1 to 3 as “disagree,” 4 as “neutral,” and 5 to 7 as “agree.” Questions about usage frequencies could be answered with one out of four values, namely “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” and “often.” Additionally, for some items (e.g., for answering RQ 3c on links between YouNow and other services) we pre-formulated answers for several questions and the users had the opportunity to add their own entries (Fig. 4). Finally, we asked for personal information (demographics).

In order to answer RQ 2c on legal concerns while broadcasting, we did not prefer to bank on user statements. Users, especially young users on YouNow, do not and maybe cannot know such legal problems. Therefore, in addition to the survey, we performed a second attempt of data collection and observed streams. This second empirical study concerns potential law violations by YouNow users (Honka et al., 2015). Here, the data set was obtained through an observation of a significant amount of streams (N = 434). A similar approach was applied by Casselman and Heinrich (2011), who analyzed YouTube videos and the behavior of their participants. The streams were observed during June 2015 and were limited to ones from Germany and the USA. The socio-demographic data was obtained either from the streamer’s profile or by asking the streamer during his or her broadcast. The observation period was divided into four parts, where different groups of streamers were in focus – females from Germany, males from Germany, females from the USA, and males from the USA. Each group was observed for an entire week. Each day of the observation was divided into four time slots (12 a.m. to 6 a.m., 6 a.m. to 12 p.m., 12 p.m. to 6 p.m., and 6 p.m. to 12 a.m.). In each slot, four streams have been investigated for 15 minutes respectively (i.e., total 16 streams or 4 hours per day).

The streams were studied for legally concerning actions. The points of reference were law infringements frequently observed in SLSSs according to German law, which is stricter than U.S. law regarding, for example, copyrights or personal rights. This way we gain a broader range of possible legally concerning actions. Demeanors in the focus of this observation were copyright infringements (concerning music pieces protected by intellectual property rights), youth protection (regarding sexual content or underage use of alcohol or drugs), personality rights (rights in one’s own picture, spoken, or written word), and defamation. The classification of a stream as one with potential law infringements was based on a rough assessment by the observer (is music being played in the background, or, are other people being filmed without their explicit consent?) and did not include a complex legal examination or consideration of exception regulations. Therefore, it is essential to emphasize that the results include only potential legally relevant actions. We analyzed the observational data quantitatively, i.e. we counted the different types of potential law infringements. All empirical data from both the survey as well as the observations became processed by Microsoft Excel.

5. INFORMATION BEHAVIOR OF YOUNOW USERS

For all empirical data from our online survey, the number of respondents is N = 123. All in all, 60.6% of the survey participants were male and 39.4% were female. According to Alexa, the amount of male visitors to YouNow is higher than the Internet average, which is confirmed by our sample. The median age of our participants was 20 years, and the most frequent age group were 16 year-old adolescents. 51.6% of our sample uses YouNow often, 11.5% sometimes, and 36.9% only rarely. As this analysis is the first step into empirical investigations on SLSSs we have to confine ourselves to descriptive statistics.

What information behaviors do users of SLSSs exhibit? There are four main activities on synchronous social networking services, namely publishing information (i.e., performing real-time), using information (i.e., watching live streams), reacting on performances (mainly by chatting), and, finally, giving rewards (e.g., by emoticons) (Fig. 2).

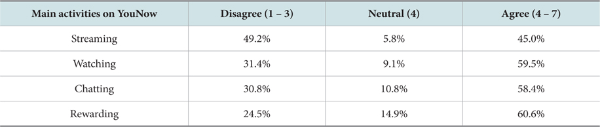

YouNow users like to watch streams (59.5% approval), to chat while watching (58.4%), and to reward performers by using emoticons (60.6%). Less than half of our respondents (45.0%) like to stream actively as well (Table 2).

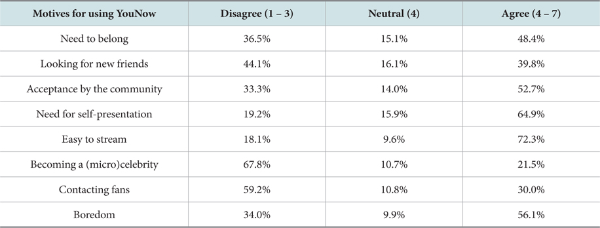

What are the motives (Lin & Lu, 2011) for using YouNow? In order to formulate adequate questions and to create accurate items on motivations for using SLSSs we consulted the literature on motives on SNSs. Following Nadkarni and Hofmann (2012), there are two main motives for using asynchronous SNSs, namely the need to belong and the need for self-presentation. We want to analyze both motives in more detail. Concerning the need to belong, Brandtzæg and Heim (2009) found a related motivation, namely to find new friends on SNSs. Additionally, we wanted to know whether it is important for a YouNow user to be accepted by the community. Is there a thing like a “we-intention” (Cheung, Chiu, & Lee, 2011) on YouNow? YouNow gives easy access to publish a stream. Is this a motive to use this service? As the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) emphasizes the perceived ease of use, a motive for users to use YouNow could be that the system provides an easy opportunity to stream. Greenwald (2013) discusses the motive of fame when using Facebook and Twitter. Are performers going to gain fame on YouNow or at least become a “microcelebrity” (Marwick & Boyd, 2011) in their community? If a user is indeed a celebrity (or believes that she/he is), is it a motive for such a user to keep contact with the fan base? Or are YouNow’s users simply bored and searching for fun?

The main motive for using YouNow is the fact that this system is easy to use (72.3% of our respondents agreed with this proposition). Next is the satisfaction of the need of self-presentation (64.9%), followed by boredom (56.1%) and acceptance by the community (52.9%). Around 50% of the test persons use YouNow because of their need to belong (48.4%) and two-fifths because they are looking for new friends (39.8%). Every fifth of our sample (21.5%) wants to become a (micro)celebrity, and 30.0% are motivated by the contacts with their fan base (Table 3).

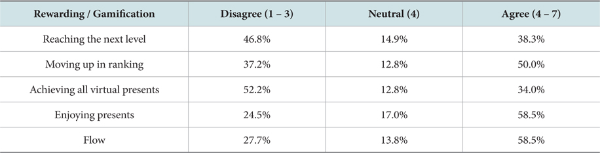

In contrast to asynchronous SNSs, YouNow is highly gamified and applies features to reward performers (Wilk, Wulffert, & Effelsberg, 2015). Gamification means the use of game mechanics in non-game contexts, to motivate users to continue using the system (Zichermann & Cunningham, 2011). Game mechanics consist, e.g., of point systems, levels, virtual goods, leaderboards, and gifts. Under certain conditions, the user has the experience of “flow” (Czíkszentmihályi, 1975), which means that one is engrossed with the system and loses awareness of other things (e.g. time). Do such game mechanics indeed motivate users to apply social live streaming services? And have they experiences of flow?

The majority of YouNow users (58.5%) enjoys receiving digital presents; for about a third (34.0%) it is an important goal to collect all kinds of presents. Moving up in the ranking of the current streamers’ playlist is important for 50.0%; and reaching the next level is essential for 38.3% of our sample. For most of our participants, gamification elements like virtual presents or levels are important motivational factors. And 58.5% had experiences of flow while using YouNow (Table 4).

6. INFORMATION PRODUCTION BEHAVIOR OF YOUNOW USERS

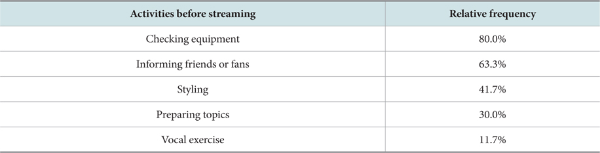

When speaking about Information production on YouNow, it means broadcasting real-time. When it comes to a performance, do users prepare themselves for the live stream? In Table 5, we only considered such test persons who had experiences with streaming. Nearly all (80.0%) checked their equipment (adjusting camera and checking microphone) before broadcasting. More than 60% of the users inform their friends or fans before the performance starts. For about 42%, styling themselves (clothes, hair, etc.) was self-evident. Some performers (30.0%) prepare their topics to talk about; and a few do vocal exercises (11.7%).

How long are the live performances (RQ 2b)? The median of all broadcasts is about one hour; however, there are streams lasting several days including periods of eating and sleeping.

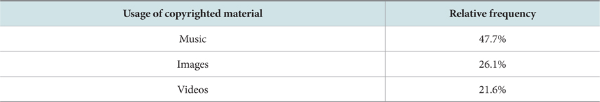

Do performers use copyrighted material? The survey participants indeed play music in the background “often” or “sometimes” (47.7%); they show, albeit to a much lesser extent, images (26.1%) and videos (21.6%) (Table 6).

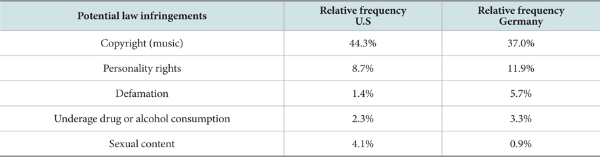

Do performers violate the law while using copyrighted material? Is there any other problematic behavior? In our second empirical study we observed streams. We found possible law infringements for both users from Germany and from the U.S. (Table 7), but there are only minor differences between streamers from Germany and the U.S. In both countries, the most common potential violation was the copyright infringement of music: a total 37.0% of German and 44.3% of U.S. streams. The second most observed potential illegal behavior concerned possible violation of personality rights. The actions chosen for this category were filming third parties, showing pictures of third parties, reading aloud chat-conversations (or similar) with third parties, or putting phone conversations with third parties on speaker during a stream, all without consent of these parties or even their awareness that their picture or their words are being brought to the public. Here, a total 11.9% of German streams and 8.7% of the U.S. streams included potential violations of personality rights. The category of defamation includes insulting remarks made by the streamer or by the audience, and were observed in 5.7% of German and 1.4% of U.S. streams. Regarding youth protection, two aspects were elaborated, the underage use of alcohol or drugs, and sexual content (revealing appearance of the streamer, or pressuring requests from viewers to the streamer to undress etc.). A total of 3.3% of German and 2.3% of U.S. streams included underage drinking or drug use, whereas 0.9% of German and 4.1% of U.S. streams had sexual content.

7. INFORMATION RECEPTION BEHAVIOR OF YOUNOW USERS

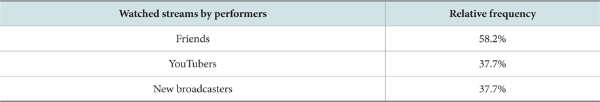

Users like to watch streams (59.6% approval; Table 2), to chat with the performer as well as with other viewers (58.4%), and to reward the performer (60.6%). What do they mainly watch? Many recipients prefer to watch streams of their friends (58.2%); more than a third of all participants (37.7%) views streams by known YouTubers as well; and also 37.7% are open for attending streams published by new broadcasters (Table 8).

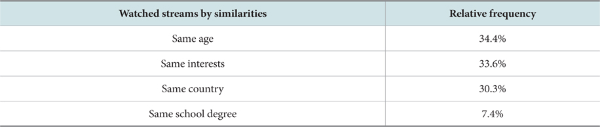

There is only a minority of users who chose streams because of similarities between themselves and the performer. About a third of our test persons watches streams by performers with the same age or shared interests, or who come from the same country. The same school diploma or degree does not play any noticeable role (7.4%).

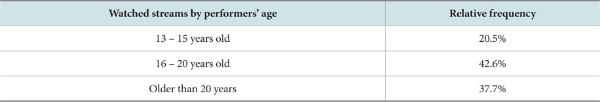

About two out of three users of our sample prefer to watch streams by adolescents between the ages of 13 and 20 (Table 10). So YouNow is a service with content mainly made by teenagers for teenagers.

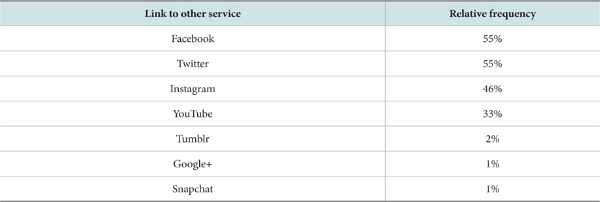

To create an account on YouNow, one has to be a Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Google+ user; there is no option to register by email address. Do YouNow users also apply these social media to establish links between their YouNow account and their accounts on other information services? As Table 11 shows, about half of the sample indeed works with links between YouNow and their sites on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. A third of the respondents links to their YouTube channel, while Tumblr, Google+, and Snapchat only play minor roles. We can state that there is a distinct multi-channel behavior of YouNow users.

8. DISCUSSION

What lessons do we learn from our studies about the information behavior on general social live streaming services? Our case study, YouNow, is a service with streams by adolescents for adolescents. YouNow users like to watch streams, to chat while watching, and to reward performers by using emoticons. 45% of our participants like to stream actively as well. The main motive for using YouNow is the simple fact that this system is easily utilized. Next is the satisfaction of the need of self-presentation, followed by boredom and intended acceptance by the community. For many YouNow users, gamification elements like virtual presents or levels are important motivational factors. Many users even report about experiences of flow while using this service. Information production on YouNow means broadcasting real-time. The median length of all broadcasts is about one hour, but we found streams lasting several days. We could observe potential law infringements while streaming, first of all copyright and personality rights violations. Many recipients prefer to watch streams of their friends and of people aged between 13 and 20 years. There is a distinct multi-channel behavior of YouNow users, as they link their YouNow accounts to other social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

There are some limitations of our empirical study. The number of respondents of the online survey is rather small (123 respondents completed the survey). The results of the investigation would be more accurate and would better represent the whole population if there were a higher number of participants. Furthermore, most of the survey participants were from Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and none from Turkey, Saudi Arabia, or Mexico, where – according to data from Alexa – a high number of site visitors originate. To get a better understanding of social live streaming services, there is need for further investigations of other live streaming platforms as well as more extensive ones about YouNow itself. Also, the legal aspects of live streaming should be analyzed in more detail. Are there indeed consequences for law infringements (e.g., after defamation or violation of personality rights)? Is the use of music really a violation of copyright or is it, especially in the United States, subject to fair use?

Information behavior on synchronous SNSs like YouNow shows some similarities to information behavior on asynchronous social media, but also major differences in some aspects. On asynchronous social media, information seeking is an essential type of information behavior (Kim & Sin, 2014). There are many hints that people use social media for seeking topic-related information, e.g. health information (Oh & Kim, 2014; Pálsdóttir, 2014; Zhang, 2013). On synchronous SNSs, there is no information seeking behavior beside the selection of the performer or the genre (via hashtags).

We find similar motives for using synchronous SNSs in comparison to asynchronous social media. Nadkarni and Hofmann (2012) reported about the need to belong and the need for self-presentation. Hsu, Chang, Lin, and Lin (2015) identified four motives which affect interactivity and in turn satisfaction and continued use, namely entertainment, socialization, information seeking, and self-presentation. Apart from information seeking, all other motives can be found on synchronous SNSs as well. The very important entertainment motives on YouNow consist of several components such as relieving one’s boredom, becoming a (micro) celebrity, and staying in contact with fans.

On asynchronous social media (as in many other regions of the World Wide Web), it is possible to create fake accounts or other selves (Bronstein, 2014). Here, the adage “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” (Steiner, 1993) is a truism. It is true for the reception side of synchronous SNSs, but definitely not for the production side. The performer may use a nickname, but you see him or her in full attire. If the performer on YouNow is a dog, everyone will realize this fact.

As a first step into the new research area of general live streaming services, this study is limited to descriptive statistics of basic empirical data on YouNow. Necessary next steps include the elaboration of a theory of information behavior on social live broadcasting services and the integration of our empirical as well as (future) theoretical results into known approaches in social media research. As research on SLSSs shows, it is important for information science to broaden its sometimes limited view only on information seeking behavior towards an entire view on users’ information-related activities, including all aspects of information production and information reception behavior.

Synchronous SNSs remind us of The Truman Show, which is an American film from 1998 presenting the life of its protagonist, Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey), in a constructed television reality show, which is live broadcasted to its audience. Truman’s life is monitored 24/7 from his birth until his escape from the studio, when he was 30 years old. However, there is a great difference: In contrast to Truman, broadcasters on YouNow are well aware of their actions. Applying YouNow, users can stream wherever they want to without any time limit – and produce their own Truman Show.

References

Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (, , , (3rd ed.)) ((2010)) New York, NY: CRC Bates, M.J. (2010). Information behavior. In M.J. Bates & M.N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed.) (pp. 2381-2391). New York, NY: CRC. , pp. 2381-2391, Information behavior

Inter-generational comparison of social media use: Investigating the online behavior of different generational cohorts((2016)) Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society Fietkiewicz, K.J., Lins, E., Baran, K.S., & Stock, W.G. (2016). Inter-generational comparison of social media use: Investigating the online behavior of different generational cohorts. In Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 3829-3838). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society. , FietkiewiczK.J.LinsE.BaranK.S.StockW.G., 3829-3838

Soziale Netzwerke im Diskurs (, ) ((2015)) Hagen, Germany: FernUniversität Henning, C. (2015). Warum durch Phänomene wie YouNow die Vermittlung von Medienkompetenz immer wichtiger wird. Ein Beitrag aus medienethischer Sicht. In T. Junge (Ed.), Soziale Netzwerke im Diskurs (pp. 199-212). Hagen, Germany: FernUniversität. , pp. 199-212, Warum durch Phänomene wie YouNow die Vermittlung von Medienkompetenz immer wichtiger wird. Ein Beitrag aus medienethischer Sicht

An analysis of the YouNow live streaming platform(26-29 Oct. 2015, (2015)) 40th Local Computer Networks Conference Workshops, Clearwater Beach, FL Washington, DC: IEEE Stohr, D., Li, T., Wilk, S., Santini, S., & Effelsberg, W. (2015). An analysis of the YouNow live streaming platform. In 40th Local Computer Networks Conference Workshops. Clearwater Beach, FL, 26-29 Oct. 2015 (pp. 673-679). Washington, DC: IEEE. , StohrD.LiT.WilkS.SantiniS.EffelsbergW., 673-679

On influencing mobile live broadcasting users(14-16 Dec. 2015, (2015)) IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia Washington, DC: IEEE Wilk, S., Wulffert, D., & Effelsberg, W. (2015). On influencing mobile live broadcasting users. In IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia, 14-16 Dec. 2015, Miami, FL (pp. 403-406). Washington, DC: IEEE. , WilkS.WulffertD.EffelsbergW., 403-406

Leveraging transitions for the upload of user-generated mobile video(May 13 2016, (2016)) Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Mobile Video, Klagenfurt, Austria New York, NY: ACM Wilk, S., Zimmermann, R., & Effelsberg, W. (2016). Leveraging transitions for the upload of user-generated mobile video. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Mobile Video, May 13 2016, Klagenfurt, Austria (art. no. 5). New York, NY: ACM. , WilkS.ZimmermannR.EffelsbergW., (art. no. 5)

About YouNow () ((2016)) YouNow (2016). About YouNow. Retrieved from https://www.younow.com/about. , Retrieved from https://www.younow.com/about