The 13 Otter Species in the World and Eurasian Otter in Korea

There are a total of 13 species of otters worldwide (Table 1) (IUCN, 2021). Among them, five are found in Asia, and only one species of Eurasian otter is found in South Korea (Fig. 1). This species has the widest range of habitat among the 13 species, and it is found in Eurasian continent and North Africa (Roos et al., 2015).

Eurasian otters are classified as a near threatened species (NT) (Table 1), and it was reported that this species is currently in a decreasing stage as habitat fragmentation and environmental destruction have been accelerated worldwide (Roos et al., 2015). The Eurasian otter species native to South Korea has been under legal protection since 1982.

Wilson and Reeder (2005) have identified a total of 12 subspecies of Eurasian otters. The subspecies found in South Korea is known as Lutra lutra lutra. However, nearly no taxonomic studies have been conducted in South Korea at the subspecies level so far.

History of Otters

Otters are semiaquatic mammal species that are mainly active in water. The otter occupies an ecological niche as a keystone species as well as a regulator that maintains healthy biodiversity in aquatic ecosystems (Mason & Macdonald, 1986). Otters have been intensively hunted in large numbers for commercial pelt harvest in the past. Fortunately, international environmental organizations, such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), were established in the mid-20th century, after which, otters received international protection (Duplaix & Savage, 2020).

In the Korean Peninsula, there are historical records stating that otter pelts were treated as a valuable, high-cost international trading item (Chunchugwan, 1863; Kim & Jeong, 1451). This leads us to believe that hunting otter for their pelts was common in the past. However, since the modern era of rapid national economic and large-scale urban development continued to spread, the otter’s natural habitat in rivers began to show the aspects of habitat fragmentation and loss. Therefore, the need to protect otters gradually emerged, and they began receiving legal protection after being designated as Natural monument (Registered number 330) in 1982 and also designated as Korean endangered species in 1998.

Because of these various protection efforts and the media’s high interest in otters, public awareness on otter protection quickly increased. Moreover, due to the otters’ cute and charismatic image, they became one of the representative iconic animals used to raise public awareness on natural ecosystems and wildlife protection.

Lessons from the Extinction and the New Appearance of Japanese Otters

In 2012, the Japanese Ministry of Environment officially declared the extinction of domestic otters (Nakanishi & Izawa, 2019). The Japanese otter population sharply declined before the 1950s due to intensive hunting for pelt and habitat destruction (Sasaki, 1995). Although Japanese otters were legally protected since 1965, they had almost been disappeared from the wild.

The last Japanese otters were found around the Shinjo River in Susaki City on Shikoku Island, Japan, in 1979 (Nakanishi & Izawa, 2019). At that time, one individual otter appeared to inhabit the Shinjo River basin from April to September. Consequently, news about the discovery of this otter became a hot topic in Japan, and many experts, photography clubs, and news outlets gathered around the Shinjo River to photograph the animal. However, this otter disappeared after a few months, and for a long time since then, no more Japanese otters have been observed. Eventually, in 2012, the Japanese Ministry of Environment officially declared the extinction of Japanese otters (Yoxon & Yoxon, 2019). According to Japanese otter researchers, their assessment on the extinction of Japanese otters revealed that leading causes of extinction were excessive pressure from hunting, aquatic environment pollution, road construction, river development, damage from net fishing, and low level of public awareness regarding its protection (Ando, 2012; Sasaki, 1995).

However, in February 2017, special news arrived from Tsushima Island, Japan. A research team led by Izawa (Ryukhus Univ., Japan) was conducting a field survey using a camera trap in Tsushima Island, and surprisingly one otter was caught on the camera (Nakanishi & Izawa, 2019). However, there have been no research records of otters living in Tsushima Island. The Japanese Ministry of Environment and a research team led by Sasaki (Chikushi Jogakuen Univ., Japan) assumed that approximately four otters are currently living in Tsushima Island based on field surveys and genetic analysis of otter spraints (Cultural Heritage Administration, 2020; Yoxon & Yoxon, 2019). Nevertheless, the exact origin or route of entry to the island remains unclear. Based on genetic investigations, it was presumed that these otters on Tsushima Island probably originated from South Korea. However, the shortest distance between Tsushima Island and the south coast of South Korea (Gyeongsangnam-do or Busan area) is approximately 50 km, a distance that otters cannot cross in the sea. Therefore, the researchers assumed that the otters might have arrived on Tsushima Island by chance on ships traveling between Busan, South Korea, and Tsushima Island, Japan or due to other unknown causes (Yoxon & Yoxon, 2019).

Eurasian Otters’ Territoriality and Linear Home Range

The first academic research on otter species in South Korea was conducted by Han (1997). Several studies have been conducted since then, and otters have been reportedly found in various rivers, from Gangwon-do to the southern seacoast of South Korea (Cha et al., 2004; Daegu City, 2019; Nam, 2004).

Unlike other terrestrial mammals, otters, a semiaquatic mammal species, are vulnerable and can only survive in linear-shaped waterways, such as rivers and streams; it is important to be mindful of this fact when describing the distribution range of otters in Korea. In other words, if the observed locations of otters are visualized at a regional scale, it is easy to make an overestimation that they are distributed in most regions of Korea. It is important to understand that otters have to live in a linearized waterway, while other wild animals mainly live in an area of polygon.

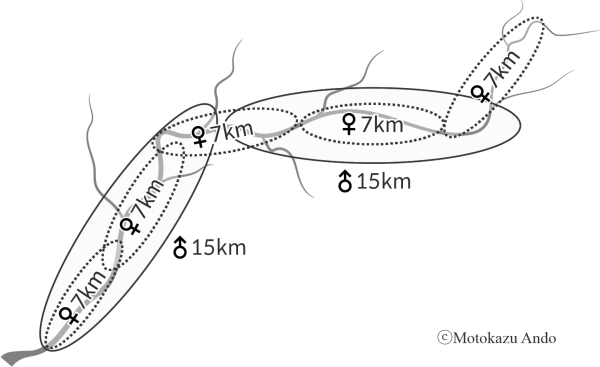

According to previous researches on the home range of Eurasian otters, Erlinge (1967) reported the otter home range is about 7-15 km, Néill et al. (2009) also reported the range about 7.5-13.5 km, reaching up to 19.5 km in some cases. Two females can be included within the territory of a male otter (Fig. 2) (Ando, 2004; Quaglietta et al., 2014). In other words, otter populations with a linear home range encounter problems more frequently than other terrestrial mammals. As otters mainly form family groups with a male and female, a competition on territory occurs when another family group breaks into their territorial domain (Remonti et al., 2011). In addition, otters are vulnerable species that can have a relatively low population size as they have to compete with each other for available food resources, which adversely affects the spread or dispersal of their gene flow.

Assessment of Otter Population Size in South Korea

In South Korea, otters are vastly popular in the public and media. When an otter is found in a particular area or dies from a roadkill, the news is quickly reported in television or online newspapers. For this reason, there has been a grave misunderstanding about the number of otters or their range of distribution. For example, a family of otters within a territory can travel upstream and downstream along their waterway several times a day, exhibiting energetic movement (Erlinge, 1967). As such, when otters move continuously from upstream to midstream, people often mistakenly assume that the otters found in the upstream, middle stream, and downstream are different individuals and that many otters live around that area. Therefore, to study the number of otters in a specific area, it is necessary not only to select an objective field survey method but also to completely understand the characteristics of their territoriality.

Fortunately, several studies have used microsatellite markers to calculate the number of otters in South Korea. Park et al. (2011) calculated the number of otters by analyzing the DNA of fresh spraints collected from areas around Daegu City. Based on this study, a total of seven individual otters were identified in the surveyed areas of Shincheon and Kumho river, which are approximately 50 km long.

The Geum River Basin Environmental Office reported the number of otters in the Daecheong Lake basin by analyzing microsatellite markers (Geum River Basin Environmental Office/Ministry of Environment, 2017). A total of 21 otters were identified through DNA analysis in the survey area, with a total water system length of approximately 230 km.

Daegu City reported the number of otters in the entire Daegu City river system, which is approximately 100 km long, and identified 19 individual otters (Daegu City, 2019).

Based on the results of such genetic analyses, the actual number of otters was determined to be relatively small (7-21 individuals), even though the habitats ranged from tens to hundreds of km. These studies evidenced the vulnerability of the otters’ linear habitat and suggest that a careful approach involving a scientific method of analysis is needed when evaluating the number of otters instead of reasoning based on a simple observation (Hájková et al., 2009; Kruuk et al., 1986; Parry et al., 2013; Sittenthaler et al., 2020).

Reproduction

The gestation period of Eurasian otters is 61-74 days (Wayre, 1979), and their average litter size is about 2.5 (Mason & Macdonald, 1986; Reuther & Festetics, 1980; Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2002; Stubbe, 1980). The reproduction period of otters varies with the latitude and environmental factors of different countries. They exhibit different characteristics depending on their habitat environments, as some reproduce over the entire year or only in a particular season (Heggberget, 1988; Kruuk et al., 1987; Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2002). For example, the otters inhabiting North America (Lontra canadensis) often shows delayed implantation of the fertilized egg (Hamilton Jr. & Eadie, 1964; Melquist & Hornocker, 1983). On the other hand, according to a study on the breeding season of Eurasian otters in South Korea (Han, 1997), most Eurasian otters give birth in the spring and sometimes also in the summer.

Diet

Otters are essentially opportunistic predators who depend on foraging of various food resources in their habitats (Rheingantz et al., 2017; Smiroldo et al., 2009). Therefore, studying the otters’ dietary habits helps in acquiring ecological information, such as their social behavior, habitat use, and population ecology. According to previous studies, fish accounts for >80% of the entire prey species of otters (Cha et al., 2004; Clavero et al., 2003; Heggberget & Moseid, 1994; Remonti et al., 2010). An analysis of the diet of South Korean otters was first reported by Han (1997), which showed that fish was their most frequent prey, followed by birds, crustaceans, amphibians, and small mammals.

Habitat Use

Several studies on the habitat use of otters in South Korea have been conducted (Han, 1997; Shin et al., 2020; Son, 2000). Han (1997) studied the otter's most preferred habitat environment at Yuncho Dam, Koje City, Gyeongsangnam-do, and found that they mostly prefer waterside environments, where rocks and vegetation coexist, whereas the place with the lowest frequency of use was an environment with a lot of mud. And Shin et al. (2020) studied the habitat use of otters from the Geum River system to the Daecheong Lake basin. The most frequently used environment was wetlands (259.3 km), followed by forests (77.0 km), grasslands (58.5 km), bare lands (51.0 km), and rockface (0.5 km). According to these results, it could be judged that otters prefer the riverside environment the most where they can readily forage for food and where various well-concealed shelters are available.

Coexistence of Humans with Otters

Otters can be found in rivers flowing through deserted forest valleys and urban streams flowing through big cities. Therefore, it is natural to find otters in river catchments, such as in Shincheon in Daegu City, Han River in Seoul City, and Jecheon in Sejong City. The appearance of otters in such urban river environments is widely observed not only in Korea but also in areas such as Hamburg in Germany and Marina Bay in Singapore (Reuther, 1995; Theng et al., 2016). However, this does not indicate their stable inhabitation. If riverbanks constitute a concrete wall environment, it is unlikely that such places would be inhabited by otters; it is likely that such places will only be used as a simple waterway to pass by (Duplaix & Savage, 2020; Foster-Turley et al., 1990). Moreover, in urban environments, roadkill by cars is very likely to occur (Raymond et al., 2021).

Whether it is an urban river or a valley in a forest, the most essential environmental condition for otters is the presence of abundant food resources and safe hideouts. Although it is important to preserve the natural habitat of otters, ecosystem restoration projects targeting already-developed urban river areas should also be considered when discussing conservation measures for otters, which can be particularly helpful. In other countries, the restoration of otter habitats generally receives public support. The New York River Otter Project in New York State (Raesly, 2001), the precedents of reintroduction of river otters in Pennsylvania, USA (Serfass et al., 2003), the restoration of otter habitats in the Ise River, Germany (Reuther, 1998), and the reintroduction of otters in the Netherlands (Jansman et al., 2003; Koelewijn et al., 2010) have all gained public support.

Shincheon in Daegu City, Korea, is adjacent to the Kumho River, Han River in Seoul City passes through the city and Jecheon in Sejong City is connected to the Geum River; therefore, ecological restoration projects in the urban streams of metropolitan cities will further expand the safe habitats of otters and may result in a healthy recovery of the ecosystem. Furthermore, restoration of otter habitat in urban streams is expected to be highly supported by the public in terms of human coexistence with otters and aquatic ecosystem restoration. Therefore, the establishment of detailed otter conservation strategies (Foster-Turley et al., 1990; Weinberger et al., 2019), such as the elimination of otter threats, improvement of their habitats, and restoration of their food resources and safe hideouts, is not only important for otter but also for a meaningful restoration process that reinstates the urban river ecosystems.

References

Chunchugwan (1863, Retrieved November 24, 2021) Joseonwangjosillok (The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty) from http://sillok.history.go.kr/

IUCN (2021, Retrieved November 24, 2021) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species from https://www.iucnredlist.org

Figures and Table

Table 1

Classification and distribution of 13 species of otters in the world (IUCN, 2021)

| Common name | Scientific name | Population trend | Species status | General distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea otter | Enhydra lutris | Decreasing | EN | Coasts of Northern Pacific Rim |

| Eurasian otter | Lutra lutra | Decreasing | NT | Eurasian continent, North Africa |

| Marine otter | Lontra felina | Decreasing | EN | Pacific Coast of South America |

| Giant otter | Pteronura brasiliensis | Decreasing | EN | South America |

| Spotted-necked otter | Hydrictis maculicollis | Decreasing | NT | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Neotropical otter | Lontra longicaudis | Decreasing | NT | Central, South America |

| African clawless otter | Aonyx capensis | Decreasing | NT | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Asian small-clawed otter | Aonyx cinereus | Decreasing | VU | South and Southeast Asia |

| Smooth-coated otter | Lutrogale perspicillata | Decreasing | VU | Southeast Asia, India, China |

| Hairy-nosed otter | Lutra sumatrana | Decreasing | EN | Southeast Asia |

| Congo clawless otter | Aonyx congicus | Decreasing | NT | Congo river basin |

| Southern river otter | Lontra provocax | Decreasing | EN | South America |

| North American river otter | Lontra canadensis | - | LC | North America |