Introduction

The black-tailed gull (Larus crassirostris) is a common seabird distributed in East Asia, including Korea, eastern China, and Japan (Park, 2014). In Korea, it is known to be a common resident bird that breeds in groups on uninhabited islands such as Dokdo, Hongdo, Chilsando and Nando (Kang et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2022). Black-tailed gulls are top predators of the food chain. As representative marine birds, they are also used as pollutant monitoring organisms (Lee et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2018). Black-tailed gulls have the characteristic of breeding in groups. Various studies have been conducted on their breeding status, growth rates, breeding population, home range, survival and return rates, habitat selection, and so on (Kwon & Yoo, 2007; Lee et al. 2008; Kang et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2022, Lee S.H. et al., 2023). Black-tailed gulls are coastal birds with different breeding and wintering habitats. After breeding, they disperse inland for the winter and show various migration patterns according to their wintering habitats (Yu et al., 2006; Xia. et al., 2023). Regarding the migration of black-tailed gulls in Korea, there are results showing that they have moved from Baengnyeongdo (in the West Sea) to China (NIBR, 2019). Studies on the annual range of black-tailed gulls on Dokdo and Hongdo have found that individuals breeding on Dokdo in winter in Japan and individuals breeding on Hongdo migrate to the southern coast area in Korea and even Japan (Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021). On the west coast of Korea, Chilsando, Bulmudo, Nando, and Baengnyeongdo are breeding grounds for black-tailed gulls, with about 50,000 individuals breeding on Chilsando (Lee et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Lee & Lee, 2022). However, the wintering population of black-tailed gulls in Korea is estimated to be approximately 55,000 in 2021-2022 (NIBR, 2022). Monthly population fluctuations are also reported in the Nakdong River Estuary, a major habitat (Hong & Lee, 2011). Seasonal migration of black-tailed gulls on Dokdo and Hongdo known to be their breeding grounds has been partially conducted. However, there is a lack of information about black-tailed gulls’ habitat use in the southwest coast near Chilsando, a large breeding site. Therefore, this study analyzed characteristics of wintering habitat use of black-tailed gulls near Chilsando on the southwest coast of Korea based on GPS tracking data.

Materials and Methods

GPS tracking data

For this study, in 2021 and 2022, 11 black-tailed gulls were captured with a Cannon-net in Yeonggwang-gun, Jeollanam-do, Buan-gun and Gochang-gun, Jeollabuk-do. These are coastal areas near Chilsando (Lee et al., 2022), a breeding ground for black-tailed gulls. A GPS tracker was attached (Table 1, Fig. 1). Capture was carried out with permission from each local government. The GPS tracker used in the study was WT-300 (22g, KoEco Inc., Korea), which was less than 5% of the average body weight (500 g) of a black-tailed gull (Lee & Lee, 2022). Data was used from October to March, which corresponds to the winter season (Xia et al., 2023). GPS coordinates were received 12 times at intervals of 2 hours per day. Open source programs QGIS version 3.x and R version 4.x were used for the analysis of the right to action. For the right of action, a package related to Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) was used. Half (50%) of the core area was used (Lee & Lee, 2022). A heat-map was used for the distribution chart. Among coordinates obtained, only coordinates with a flight speed of 5 km/h or higher were defined as flight for black-tailed gulls.

Statistical Processing

Normality was confirmed by conducting the Shapiro-Wilk test to find out monthly differences in total home range, total flight rate, and day and night flight rates of black-tailed gulls. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed for the right to action and the flight rate. If there was a significant difference, the post-test was performed through Dunn’s test. For all analyses, the significance level was set at p < 0.05 level. SPSS version 22 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Wintering habitat

Wintering habitats of black-tailed gulls on the west coast were confirmed to be inland coastal areas, islands areas the southwest coast (Heuksando, Hongdo, Chujado, Gageodo, Jejudo), and China (Table 2). As for their monthly use, the using rate of the inland southwest coast area was high in October and November and the using rate of island areas (Heuksando, Hongdo, Chujado, Gageodo and Jejudo) was high from December to February. In March, the using rate of the inland southwest coast area was high as it moved north from the wintering area (Fig. 2).

Home range

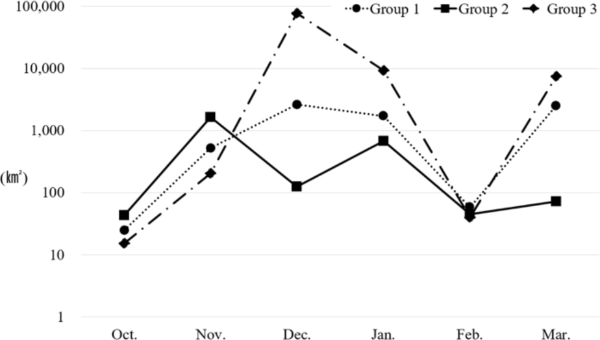

During the wintering period, the home range was narrowest in October and widest in December (Fig. 3). When black-tailed gulls were grouped by wintering area, they were divided into three groups. Group I with wintering area in islands of Korea expanded its home range from November and showed the maximum home range in December. After decreasing in February, its home range widened again in March. Group 2 with wintering area on the inland coast of Korea showed the widest home range in November. Its home range then decreased from December (Table 3, Fig. 3). Group 3 with wintering area in China had a mixture of the home range of groups 1 and 2. Its monthly home ranges were different (χ2 = 29.121, df = 5, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed significant differences between October and December and between December and February (October vs. December: p < 0.001, December vs. February: p < 0.001).

Flight rate

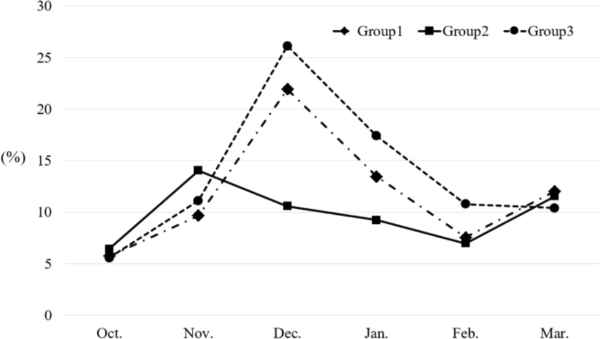

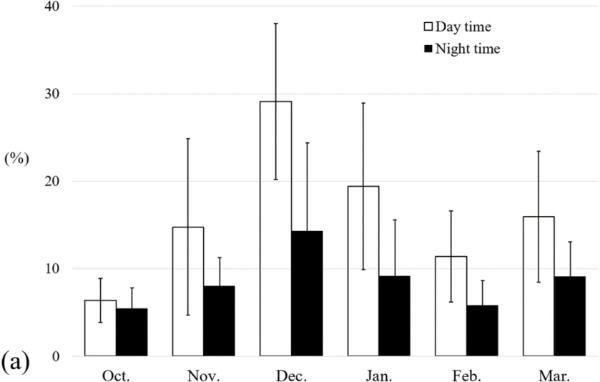

During the wintering season, the flight rate tended to be the lowest in October (5.8%) and the highest in December (20.8%). Group 1 (island areas) showed an increase in flight rate starting in November, showing a maximum flight rate in December, decreasing in February, and then increasing again in March (Fig. 4). Group 2 (inland coastal) had the highest flight rate in November. The flight rate then tended to decrease. It then increased in March. Group 3 (China) showed a flight rate similar to Group 1. Monthly flight rate was different (χ2 = 28.473, df = 5, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis results showed significant differences between October and January, between November and March, and between January and March (October vs. January: p = 0.028, November vs. March: p = 0.003, January vs. March: p < 0.001). The mean daytime flight rate was 16.4% (SD = 3.6%) and the mean nighttime flight rate was 8.7% (SD = 3.7%), showing a significant difference between the two (Fig. 5. Z = -4.494, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Most black-tailed gulls on the southwestern coast of Korea migrate to their wintering grounds in December. They can be divided into three groups based on their major wintering grounds: Group 1, southwest coast island area (Heuksando, Chujado, Gageodo, Jejudo etc.); Group 2, inland coastal area; and Group 3, China. Migration to wintering grounds begins in September on Hongdo (southeast coast), July and August on Dokdo (east sea), and begins southward migration in November on Xingrentuo Islet, China (Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2023). In this study, most black-tailed gulls on the west coast migrated to their wintering grounds in December, showing a similar tendency to black-tailed gulls breeding on Xingrentuo Islet, China. Black-tailed gulls show many different distances and patterns of migration to their wintering ground (Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2023). Winter migration of black-tailed gulls is highly correlated with temperature drop. Marine environment (food resources) and human activities (fishing boat) are also important factors affecting their winter migration (Rock, 2016; Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2023).

Black-tailed gulls on the southwest coast lived mainly in ports on the inland coast in October, showing a narrow range of action and a low flight rate. Their post-breeding period is an important energy storage period for migration. Movement is minimized during this period. It is known that the same habitat as the breeding season is used when food is abundant or a resting place is provided (Kim et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2023). Therefore, October is the post-breeding period. The inland coastal port area is thought to provide abundant food and resting places, resulting in a narrow home range and a low flight rate. From November, it was confirmed that they were moving more than 100 km into the sea around the coastal port. Some individuals used waters of the southwest coast island.

Black-tailed gulls use anchovie (Engraulis japonicus), Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes personatus), and shrimp (Amphipoda) as food sources (Kim et al., 2017). They also eat invertebrates and shellfish. They follow fishing boats (Lee S.H. et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2023). The reason for the increase of home range from November might be due to the distribution of food resources and the increase in fishing activities in the west coast. In December, island areas were widely used, focusing on Chujado and Gageodo on the southwestern island areas. Some individuals also used inland port areas (Fig. 2). The reason why black-tailed gulls widely use island areas of the southwest coast in December is also thought to be result of the distribution of food resources and the increase in fishing activities by fishing boats (Acros & Oro, 1996; Lee et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2023). In addition, this movement is considered an activity to explore wintering areas, such as checking food resources and resting places to select a wintering area (Xia et al., 2023). However, some individuals persisted in inland coastal ports. The reason why they continue to use the inland coast in December might be because they want to stay as long as possible in a familiar environment with abundant food resources and a place to rest (Xia et al., 2023) and then move when the temperature drops. The main use areas in January and February showed clear differences by group, with Group 1 using the southwest coastal island area, Group 2 using the inland port area, and Group 3 using China. All flight rates showed a decrease. Black-tailed gulls feed during day and night. Their main feeding areas include various areas such as ports, coasts, oceans, residential areas, commercial areas, and rice fields (Yoda et al., 2012; Rock et al., 2016; Lee S.H. et al., 2023). Therefore, the reason why black-tailed gulls have a very narrow home range and flight rate during the main wintering season is thought to be the result of choosing a wintering strategy of opportunistic foraging through day and night flights in various environments during the wintering season. In March, they return to their breeding grounds. Their home range and flight rate are increased. When black-tailed gulls return to their breeding grounds in March, they return to the same breeding grounds and make exploratory movements to search for food resources and select a mate during the pre-breeding period (Xia et al., 2023), which might have increased their home range and flight rate.

In this study, black-tailed gulls showed a narrow home range in October before moving to their wintering grounds. Their home range increased from November, showing the widest home range in December. These results were similar to results of a previous study showing that black-tailed gulls had a narrow home range in their wintering grounds on the west coast (Lee S.H. et al., 2023). However, these results were different from other research studies showing that the non-breeding season had a narrower right of action than the breeding season (Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022). Since home range during the breeding season was not analyzed in this study, the difference between breeding and non-breeding seasons could not be clearly confirmed. Thus, follow-up research should analyze their home range during the breeding season.

Black-tailed gulls show high returning to the same breeding site (Hong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Seo et al., 2023). They have unique genotypes according to their breeding sites (Jeong et al., 2018). However, the genetic diversity of domestic black-tailed gulls is moderate. Active gene flow between breeding populations has been reported (Lee Y.S. et al., 2023). Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the difference in wintering distribution areas between east and west coasts is due to genetic differences between breeding groups. Follow-up research is necessary. There were differences in migration time and migration patterns between black-tailed gulls on east and west coasts. These results are thought to reflect wintering characteristics of the west coast population, environmental factors such as the marine environment and fishing activities, and geographical characteristics of the west coast, where many islands are distributed. However, black-tailed gulls sometimes choose different wintering sites every year. They also choose different habitats for wintering, pre-breeding, breeding, and post-breeding (Xia et al., 2023). Continued research on habitat use characteristics among breeding groups of black-tailed gulls will be needed in the future.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Wintering area of black-tailed gulls on the west coast of Korea (a: October, b: November, c: December, d: January, e: February, f: March).

Table 1

Overview of Black-tailed gull tracking data from study site.

| Study site | No. of trackers |

Tracking period | No. of data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buan-gun | 3 | Oct. 1, 2022 ∼ Mar. 31, 2023 | 6,710 |

| Gochang-gun | 4 | Oct. 1, 2022 ∼ Mar. 31, 20231) | 8,863 |

| Yeonggwang-gun | 4 | Oct. 1, 2021 ∼ Mar. 31, 2022 | 8,460 |

| Total | 11 | 24,033 |

Table 2

Main wintering area of black-tailed gulls.

| Study site | GPS No. | Move south | Move north | Main wintering area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buan-gun | sg2202 | Dec. 09 | Feb. 12 | Chujado |

| sg2205 | Nov. 03 | Mar. 19 | Heuksando Hongdo Jejudo | |

| sg2217 | Dec. 04 | Mar. 03 | China (Taizhou) | |

|

|

||||

| Gochang-gun | sg2211 | Nov. 29 | Jan. 25 | Heuksnado Gageodo Jejudo |

| sg2212 | Nov. 05 | Feb. 27 | Jindo | |

| sg2214 | - | - | Buan-gun | |

| sg2215 | - | - | Buan-gun | |

|

|

||||

| Yeong-gwang-gun | Pkjs2101 | Dec. 12 | Mar. 23 | Chujado |

| Pkjs2102 | Dec. 19 | Mar. 28 | Chujado | |

| Pkjs2104 | Dec. 27 | - | China (Ningde) | |

| Pkjs2106 | Dec. 07 | Mar. 28 | Gageodo | |

Table 3

Black-tailed gull’s monthly Home range (KDE 50% area (km2)).

| Group | GPS No. | 2021 | 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | |||

| 1 | sg2202 | 28.7 | 477.6 | 432.4 | 84.3 | 16.5 | 14.8 | |

| sg2205 | 55.3 | 519.4 | 2,083.3 | 30.5 | 0.8 | 8,820.5 | ||

| sg2211 | 2.4 | 263.8 | 1,924.6 | 1,1497.8 | 9.7 | 94.2 | ||

| sg2212 | 1.1 | 384.8 | 1,377.6 | 241.4 | 376.8 | 3,812.8 | ||

| pkjs2201 | 5.8 | 12.5 | 3,253.0 | 113.1 | 0.8 | 3,177.6 | ||

| pkjs2202 | 6.7 | 98.6 | 3,207.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 330.4 | ||

| pkjs2206 | 73.5 | 1,902.8 | 5,991.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1,373.7 | ||

| Mean±SD | 24.8 ±29.1 |

522.8 ±636.8 |

2,609.9 ±1,789.3 |

1,709.7 ±4,317.0 |

58.2 ±140.6 |

2,517.7 ±3,164.1 |

||

|

|

||||||||

| 2 | sg2214 | 14.6 | 102.2 | 193.0 | 281.2 | 74.4 | 133.2 | |

| sg2215 | 71.8 | 3197.2 | 53.7 | 1,081.1 | 15.6 | 11.7 | ||

| Mean±SD | 43.2 ±40.5 |

1,649.7 ±2,188.5 |

123.4 ±98.5 |

681.2 ±565.6 |

45.0 ±41.6 |

72.5 ±86.0 |

||

|

|

||||||||

| 3 | sg2217 | 1.0 | 107.3 | 9,5651.5 | 1,8371.9 | 61.2 | 14,838.1 | |

| pkjs2204 | 29.6 | 301.3 | 57,674.4 | 54.1 | 18.7 | 4.5 | ||

| Mean±SD | 15.3 ±20.3 |

204.3 ±137.2 |

76,662.9 ±26,853.9 |

9,213.0 ±12,952.7 |

40.0 ±30.1 |

7,421.3 ±10,489.0 |

||