JOURNAL OF INFORMATION SCIENCE THEORY AND PRACTICE

- P-ISSN2287-9099

- E-ISSN2287-4577

- SCOPUS, KCI

A New Explanation of Some Leiden Ranking Graphs Using Exponential Functions

Abstract

A new explanation, using exponential functions, is given for the S-shaped functional relation between the mean citation score and the proportion of top 10% (and other percentages) publications for the 500 Leiden Ranking universities. With this new model we again obtain an explanation for the concave or convex relation between the proportion of top 100θ% publications, for different fractions of θ.

- keywords

- Leiden ranking, exponential function, mean citation rate, S-shaped

1. INTRODUCTION

For 500 universities (from 41 countries) from the Leiden Ranking 2011/2012 one observes in Waltman et al. (2012) the relation between the mean normalized citation score (MNCS) and the proportion of top 10% publications (PPtop10%).

Upon specifying a field, MNCS is the mean number of citations of the publications of a university in this field (normalized in several ways – see Waltman et al.). PPtop10% is the proportion (fraction) of the publications of a university in this field that, compared with other publications in this field, belong to the top 10% most frequently cited.

In Waltman et al. one finds an S-shaped relation between PPtop10% and MNCS: first convex then concave (see their Fig. 2). Allowing some other percentages, Waltman et al. find a convex relation between PPtop10% (as abscissa) and PPtop5% (as ordinate) and a concave relation between PPtop10% (as abscissa) and PPtop20% (as ordinate) – again see their Fig. 3.

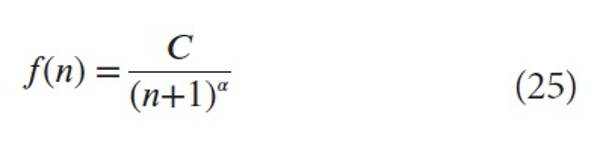

In Egghe (2013) we explained all these regularities using the shifted Lotka function

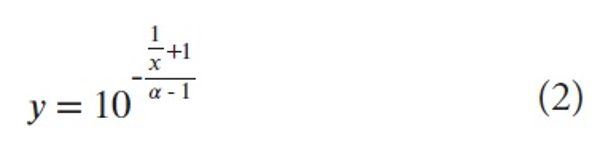

where C > 0, α >1, n ≥0, which was documented in Egghe and Rousseau (2012). Here f(n) is the continuous version of the number of publications with n citations. Using (1) we studied the functional relation between the non-normalized variant of MNCS, denoted MCS and PPtop10% . Putting x =MCS and y = PPtop10% we proved in Egghe (2013) that

where α is the exponent of Lotka in (1), where we also proved the S-shape, hereby explaining this empirical relationship in Waltman et al. (2012).

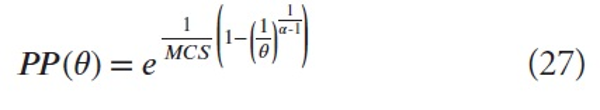

For general fractions θ we obtained in Egghe (2013)

where x =MCS and y = PP(θ)≕PPtop 100θ%.

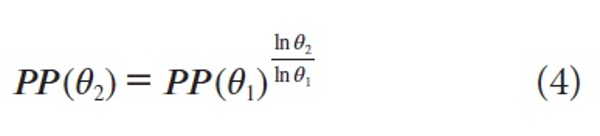

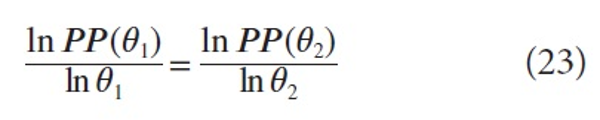

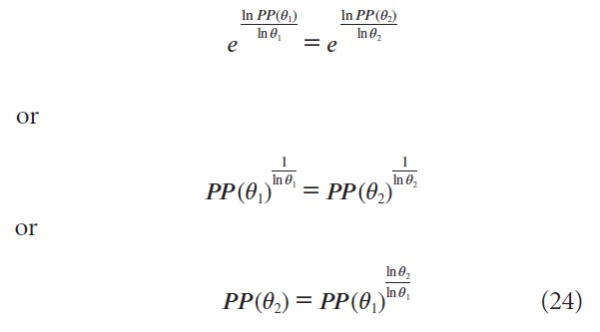

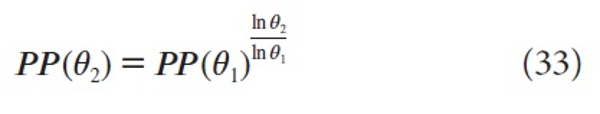

From this model we proved, for any fractions θ1, θ2, the following functional relation between PP(θ1) and PP (θ2) :

which is an explanation of the convex and concave graphs in Waltman et al.: concave if θ2>θ1 and convex if θ2<θ1.

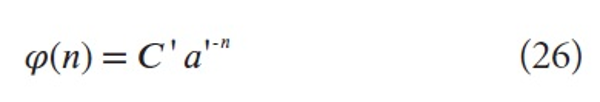

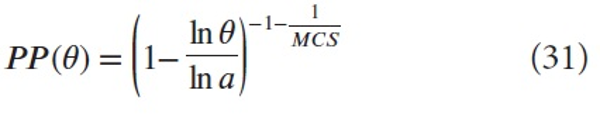

In this paper the same problems are studied: explaining the S-shaped relationship between MCS and PP (θ) for any θ and the convex or concave relationships between two PP (θ1) and PP (θ2) as found in Waltman et al. Now, however, we do not use the shifted Lotka function (1) but the exponential function (a very classical function)

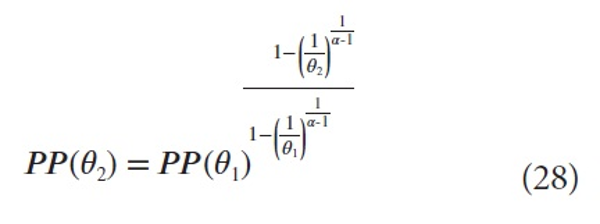

where C>0, α>1, n≥0 where the function f(n) has the same meaning as explained above. With x = MCS and y=PP (θ) we will prove (in the next section) that

which is a clearly different function when compared with (3). But also this regularity explains the one found (empirically) in Waltman et al. since (6) is also Sshaped.

Remarkably, in the third section, using (6) for two fractions θ1 and θ2, we will reprove (4); i.e., the same regularity between any two PP (θ1) and PP (θ2) is found using exponential functions as when we used the shifted Lotka function (which are clearly different functions). But, at the end of the paper, we will also give two cases where (4) is not valid.

The paper closes with a conclusion and open problems section.

2. EXPLANATION OF THE RELATION BETWEEN MCSAND PP(θ)

As indicated in the introduction we use the exponential function

denoting the continuous version of the number of publications with n citations in a field where C>0, α>1, n ≥0. Since the field is fixed, we have also that C and α are fixed.

For a university we use the exponential function

(C’> 0, α’>1, n ≥0 ) denoting the continuous version of the number of publications of this university with n citations. Since we deal with several universities (e.g. 500 in the case of Waltman et al. (2012)) we have here that C’and α’ are variables.

As noted by one referee, the fact that, per university, we use (8) with C’and α’ variables, does not necessarily lead to (7) for the entire field. Therefore, formula (7) should be considered as an assumption to be valid in practice:

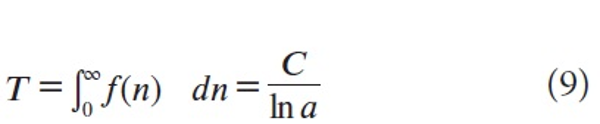

Denote by T the total number of publications in the entire field and by T’ the total number of publications in a university in this field. We have, by definition of f(n)

(since α>1) and similarly

Denote by A the total number of citations in the entire field and by A’ the total number of citations in a university in this field. We have, by definition of f(n)

which is easily seen using partial integration, by the fact that α>1 and the fact that

Similarly we have

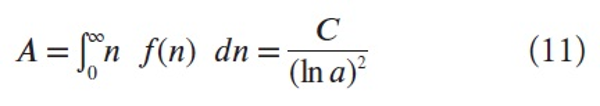

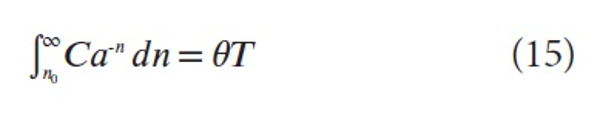

By definition of MCS, being the average number of citations per publication of a university, we have

, using (10) and (13).

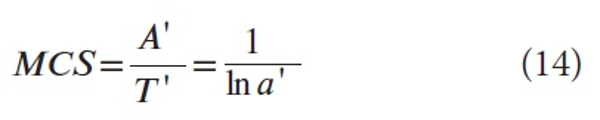

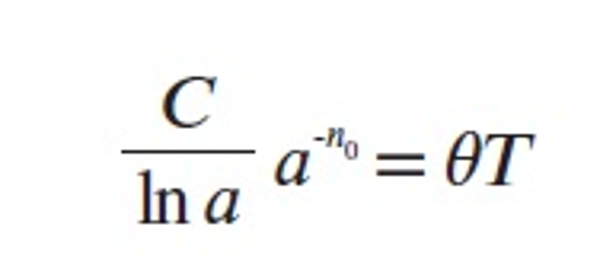

We first determine n0 defining the top 100θ% publications in the field (for any fraction θ), by (7) :

From (15) it follows that

and by (9) we have

which is a positive number because 0<θ<1.

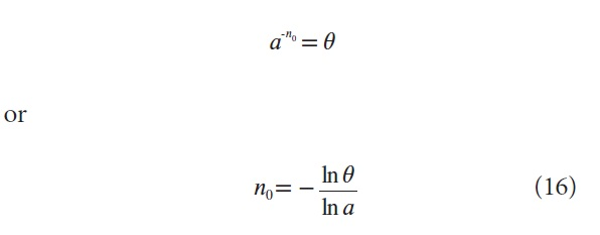

Then the university proportion in these top 100θ% of the papers in the field is, by (8)

(by (16))

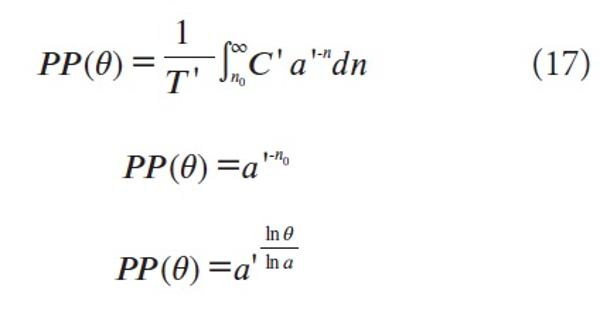

(by (14)) or the function (6). This is an increasing function (since 0<θ<1) for which (x = MCS)

and

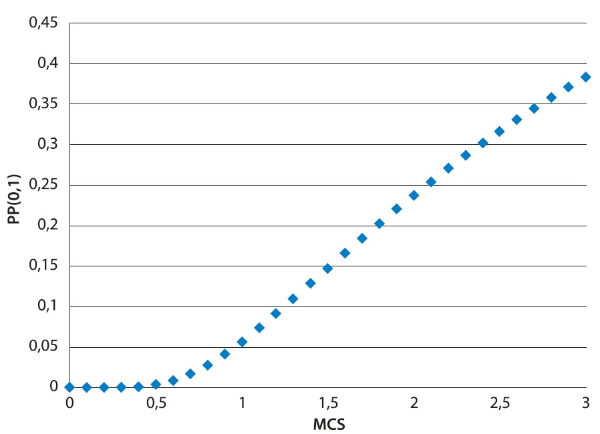

The number α is a fixed parameter (of the field). Fig. 1 is the graph of (18) for ln α=0.8 from which the Sshape is clear, and it is close to the S-shape obtained in Waltman et al. (2012). So this represents a new explanation of this regularity.

3. EXPLANATION OF THE RELATION BETWEEN ANY TWO VALUES OF PP(θ1) AND PP(θ2)

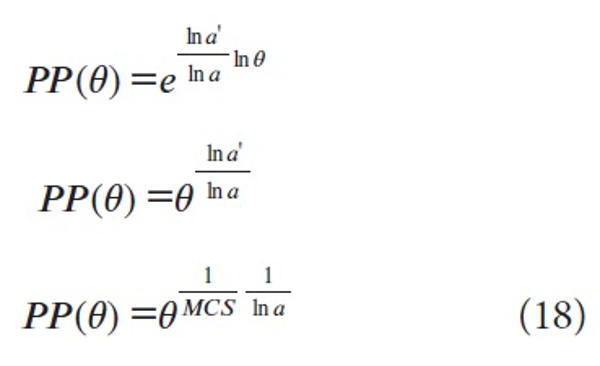

For any two fractions θ1 and θ2 we have, by (18)

Hence

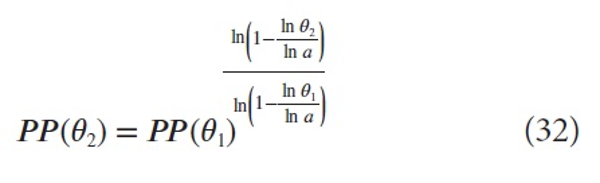

from which it follows that for any two fractions θ1 and θ2

hence

which is (4).

As already remarked in the introduction, this relation is the same as the one found in Egghe (2013) where the shifted Lotka function was used, a remarkable fact!

We have derived that (since 0< θ1, θ2< 1), if θ2 > θ1 , then (by (24)), PP(θ2) is a concave function of PP(θ1) and that, if θ2 < θ1, then (by (24)), PP(θ2) is a convex function of PP(θ1) – see the graphs in Egghe (2013) which explain the corresponding graphs in Waltman et al. (2012).

So (24) is valid when f and φ are both shifted Lotka functions (proved in Egghe (2013)) and when f and φ are both exponential functions (proved here). Now we present two cases where (24) is not valid.

Case I

We take f to be a shifted Lotka function and φ to be an exponential function:

(C’> 0, α’>2, n ≥0 )

(C’> 0, α’>1, n ≥0 ) Following the method of the previous section we find, for every fraction θ

From the method in this section we find, for any two fractions θ1 and θ2,

which is, clearly, not the function (24).

Case II

We take f to be an exponential function and θ to be a shifted Lotka function:

(C’> 0, α>1, n ≥0 )

(C’> 0, α’>2, n ≥0 ) Following the methods of the previous section we find, for every fraction θ

From the method in this section we find, for any two fraction θ1 and θ2 ,

which is, clearly, not the function (24).

4. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Experimental regularities in Waltman et al. (2012) are proved mathematically in this paper. Using the exponential function we proved the S-shaped functional relation between the mean citation rate and the proportion of top 100θ% publications. We obtained a different function than in Egghe (2013) where a shifted Lotka function was used, but we obtained an S-shape in both cases.

With this new model we could reprove the function (obtained in Egghe (2013))

for the relation between two PP (θ)-values. It is very remarkable that we obtain exactly the same function as in Egghe (2013) although different starting functions were used (shifted Lotka in Egghe (2013) and exponential here). We also showed that (33) explains the corresponding empirical regularities in Waltman et al. (2012).

The importance of this paper is that the assumption of a simple exponential function (5) leads to an explanation of several regularities in Waltman et al.

We state as an open problem: can the S-shape in Waltman et al. for the relation between the mean citation rate and the proportion of top 100θ% publications be proved using other starting functions (other than the shifted Lotka function and other than the exponential function)?

Also the following is an open problem: characterise the functions F(n) and φ(n) (previous section) for which (33) is valid. From Egghe (2013) and this paper, this class of functions must include the shifted Lotka function and the exponential function.

- 투고일Submission Date

- 2013-07-17

- 수정일Revised Date

- 게재확정일Accepted Date

- 2013-08-06

- 다운로드 수

- 조회수

- 0KCI 피인용수

- 0WOS 피인용수