JOURNAL OF INFORMATION SCIENCE THEORY AND PRACTICE

- 권한신청

- P-ISSN2287-9099

- E-ISSN2287-4577

- SCOPUS, KCI

Organizational Justice and the Intent to Share: Knowledge Sharing Practices among Forensic Experts in Turkey

Suliman Hawamdeh (College of Information University of North Texas)

Abstract

Organizational climate and organization culture can be some of the leading factors in hindering knowledge sharing within the organization. It is generally accepted that successful knowledge management practice, including knowledge sharing, comes as a result of a conducive and knowledge sharing friendly environment. Organizations that promote and reward collective work generate a trustful and a more collaborative learning culture. The perception of fairness in an organization has been considered an important indicator of employee behavior, attitude, and motivation. This study investigates organizational justice perception and its impact on knowledge sharing practices among forensic experts in the Turkish National Police. The study findings revealed that senior officers, who are experts in the field, have the strongest organizational justice perception. Meanwhile, noncommissioned officers or technicians bear positive but comparatively weaker feelings about the existence of justice within the organization. The study argues that those who satisfy their career expectations tend to have a higher organizational justice perception.

- keywords

- Forensic Experts, Knowledge Sharing, Intention to share, Organization Justice, Turkish National Police

1. INTRODUCTION

In today’s increasingly competitive world economy, knowledge is considered a key factor in gaining competitive advantage and managing intellectual capital for both public and private organizations. An organization’s value, asset, and wealth is measured through innovation, knowledge accumulated over time, and the organization’s ability to transform that knowledge into products and services (Grant, 1991; Teece, 2000; Bock et al., 2005). The development and transformation of individual knowledge and expertise into organizational knowledge requires heavy investment in people and human capital. It requires investment in the processes and practices that enable organizations to identify and manage the knowledge resources and intellectual capital.

A number of studies in knowledge management focus on law enforcement agencies including the Turkish National Police (TNP). Some of these studies have concentrated on knowledge management practices such as knowledge sharing, leadership, and job satisfaction. However, none of these studies have dealt with the relationship between knowledge sharing and organizational justice. This study is an attempt to address the gap in the literature by focusing on organizational justice and its relationship to knowledge sharing, in particular issues affecting forensics knowledge sharing practices. The Department of Police Forensic Laboratories (DPFL) in the Turkish National Police employs over 600 experts, assistants, and technicians in a variety of forensic branches (Personal Communication, 2012). The forensics in the TNP, examine numerous cases as an important part of the judicial process. According to annual statistics from the DPFL, over 215,000 pieces of evidence were investigated by the forensics in 2011 (Personal Communication, 2012).

During these operations, knowledge sharing plays a significant role in enhancing communication and improving operational effectiveness. Previously, there is no research that has investigated knowledge-sharing intentions among forensic experts in the TNP. Thus, it is considered valuable to study the influence of organizational justice perceptions on knowledge sharing.

The purpose of this research is to investigate organizational justice perception and its relationship to knowledge sharing among forensic experts in the TNP. The study will provide recommendations that will serve as a foundation for establishing a better policy for creating a more equal and fair work environment that encourages employees to improve their knowledge sharing practices and communication skills. It is also expected to be a contributing factor for managing intellectual assets and improving performance within the TNP. As a result of this study, it will be possible to disclose the problems related to organizational justice practices and knowledge sharing channels exercised by forensic experts in their work environment.

2. ORGANIZATIONAL JUSTICE

In equity theory, fairness is deemed as giving and receiving proportionally (Adams, 1963). The equity theory suggests that employees put their time, effort, and knowledge (inputs) into work and in return they receive wages and compensations (outcomes) as a form of reward and recognition. The balance between inputs and outputs are subjectively judged based on individual perceptions and in some cases a criteria developed for assessing and measuring performance. When employees think that an outcome does not fit their input then the notion of inequity emerges (Greenberg, 1990a). Restoring the perception of equity to an acceptable level reduces tension at the work place and enhances productivity. At the same altering employees’ perceptions about circumstances may reduce the perception of unfairness (Weller, 1995; Greenberg & Baron, 2003).

Organizational Justice can be defined as the general perception of fairness in an organization and the perception of how decisions are made with regard to rewards and compensations. The existence of organizational justice has been considered an important indicator of employee behavior, attitude, and motivation. Employees who perceived that they were treated fairly by organizations tend to be more committed to the organization mission than those who perceived they were treated unfairly (George & Jones, 2007; Cohen- Charash & Spector, 2001).

Four different types of constructs are used in the literature to explain and understand organizational justice. These are distributive justice, procedural justice, interpersonal justice, and informational justice (George & Jones, 2007; Ibragimova, 2006). Distributional justice is referred to as perceived fair distribution of outcomes such as promotions, payments, and a desirable work environment. Procedural justice is the judgment of the procedures exercised to make decisions for distribution of outcomes. Interpersonal justice is the perceived fairness of the interpersonal treatment implemented by the distributors of outcomes, or in other words managers. Employee perception of informational justice is defined as the explanation of the decision-making process and procedures implemented based on these decisions (George & Jones, 2007).

While an organizational climate constructs explicit dimensions of the organization such as reward systems and promotions, organizational culture bears a system of meanings that explains organizational behavior, stories, and special language. An organizational climate includes established structures that control relations (Ibragimova, 2006). The researcher assumes a positive relation between a conductive organizational climate, subjective norm, and intention toward knowledge sharing. Simons and Roberson (2003) investigated the relationship between collective procedural justice and interpersonal justice perceptions and how these affect the organizational outcomes. The study was conducted in 111 different hotels in the US and Canada among 13, 239 employees through employee surveys. Simons and Roberson (2003) measured justice perceptions: commitment, guest satisfaction, intent to remain with the organization, and employee turnover. The results revealed that procedural and interpersonal justice perceptions contribute to the overall organizational outcomes in variations. Operational and management level success is observed through collective organizational justice perceptions of employees and improving fair treatment of employees for competitiveness and commitment.

Studies also examined organizational justice perception as an antecedent of organizational commitment. Commitment concept is discussed in three forms: affective commitment, which is emotional attachment to the organization, normative commitment, which is responsibility to the organization, and continuance commitment, which are combined as consequences associated with leaving the organization (Jamaludin, 2011; Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, 2001). The study by Jamaludin involved 290 academic staff employed in a public learning institution. The study found that organizational justice forms have significant effects on the development of commitment. Moreover, distributive justice was observed as a significant influence on remaining with the organization. However, motivation factors are differentiated as material motivation factors and non-material motivation factors. As the employees motivated by the earlier are concerned with distributive justice, the latter motivated employees are focused on procedural justice.

Crow and his team carried out a survey in 2012 that involved 418 police officers to examine relations between organizational justice constructs, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. The study explored the relationship between organizational justice and organizational commitment using job satisfaction as a mediator. The study found that there is significant relation between organizational commitment and distributive justice when it is supported with other forms of organizational justice. They argued that procedural justice and interactional justice influenced the distributive justice perception, not organizational commitment. Nevertheless, the influence of distributive justice perception was not significant when job satisfaction was added as a mediator to the proposed model. The study proposes that supervisors should play a key role in nurturing police officers’ perception of justice by developing good relationships with their subordinates when evaluating them, with fairness and well-defined standards (Crow et al., 2012).

3. THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Several theories and models have been proposed and used to explain information users’ preferences and adoption of systems and technology, including Rogers’ (1995), Davis’ (1989), and Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) theories. So far, these theories appear to provide the best understanding about information user behavior, satisfaction, understanding, and evaluation of usercentered systems.

In real-world situations, knowledge sharing can be facilitated and encouraged in several ways, including compensations (economic), acknowledgement & recognition (social-psychological), and generating fairness (sociological) at work (Bock et al., 2005). Fairness or justice is a sociological phenomenon that has been observed and studied in every aspect of life for decades. In equity theory, Adams (1965) emphasizes that outcomes, in other words meaning distributions, determine individual differences on work attitudes and behavior. However, the notion of justice is not limited or related to the outcomes only. Research revealed that people are concerned about the decision-making processes as well as the decision itself (Sillito-Walker, 2009). Earlier studies highlighted that organizational justice has been associated with organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a linear direction (Crow et al., 2011). Organizational justice is a part of management in order to enhance work environment and increase work satisfaction and productivity. Knowledge sharing practice is a contributing factor to the intellectual assets of an organization through its human capital. Thus, organizational justice perception has been assumed to be an antecedent to behavioral intentions such as the intention to share knowledge (Sillito-Walker, 2009).

Since Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) stems from a self-motivated behavior, it is recognized that organizational justice factors are significant forecasters of OCBs (Organ, 1990). Research suggests that perception about fairness at work place increases OCB since there is a contributory relationship between organizational justice and OCB (Moorman, 1991; Chegini, 2009; Jafari & Bidarian, 2012). Organ (1988) stressed that the level of OCB could be an indicator of inequity in an organization. Since OCB is both discrete and supplementary, it is not measureable and is not included in the job description. Research suggests that we are likely to observe changes in OCB related to the

fairness perceptions (Moorman, 1991).

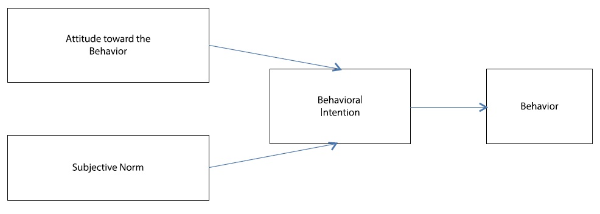

The theoretical foundation of this research is based on Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975; 1980) theory of reasoned action (TRA). According to this theory, behavioral beliefs and evaluation of the consequences determine an individual’s attitude (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). TRA stresses that actual behavior is represented by behavioral intention, which is a measure of intention required to perform. In other words, behavioral intentions are a summary of motivation to act (Ibragimova, 2006). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975; 1980) argue that an individual’s behavioral intention is a predictor of the behavior itself. TRA is constructed on three components: behavioral intention, subjective norm, and attitude (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1975; 1980). At a glance, the theory gives an impression of simplicity; however, it is as complex as human behavior (see Figure 1). Emerging from social psychology, the theory has been tested in various areas ranging from consumer traits to health related daily activities (Madden et al., 1992; Hale et al., 1997).

The principal assumption of the theory originated in the idea that intentions are the best predictors of behavior. Intention represents cognitive readiness to perform a particular behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The TRA specifies the factors and incentives that cause any behavior. The theory predicts that an individual’s behavior —in this case knowledge sharing—is determined by intention to share knowledge (Tao, 2008). Actual behavior is triggered by behavior intention, which is supported by attitude toward performing a behavior and by subjective norm. Simply put:

Attitude + Subjective Norm → Behavior Intention → Actual Behavior

It is assumed that individuals control their behavior voluntarily. By this assumption, individuals consider the consequences or implications of their actions before they act. Thus, intention has been strongly associated with behavior. Behavior is a meaning of two components in this equation: attitude, which represents an individual’s evaluation of performing behavior, and subjective norm, which is the sum of expectations by the people around this individual and the individual’ s motivation to comply (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Tao, 2008).

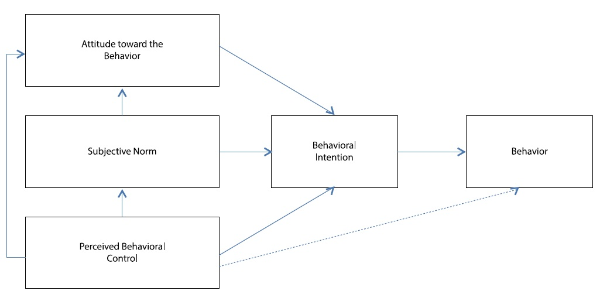

Due to limitations on explaining intention with attitude and subjective norm, Ajzen (1991) introduced another determinant factor: perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavior control refers to people’s confidence level about their ability to perform a specific behavior. This addition generated a new theory called the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (see Figure 2). Ajzen (1985; 1991) argued that perceived behavioral control influenced behavior as well as attitudes and subjective norms. He emphasized that behavior is not voluntarily controlled all the time. Ajzen (1991) asserts that behavior determines outcomes in general; however, knowing perceived behavioral control along with subjective norms and attitude toward the behavior

predicts the likelihood that the intention becomes behavior.

Knowledge sharing and management research has focused on various topics including organizational justice, OCB, job satisfaction, and organizational culture. However, research investigating the relationship between organizational justice, OCB, and knowledge sharing is limited. Thus, the linear relationship observed in previous research (Moorman, 1991; Bock et al., 2005; Ibragimova, 2006; Crow et al., 2011) is tested in a different sample.

4. RESEARCH METHOD

Studies are conducted for identifying, uncovering, and explaining facts in different fields or environments. According to Marshall and Rossman, (1989) survey and experimental research are approaches used by researchers who examine the relationship between fixed concepts and standard variables. A research design is the outline of data collection and analysis. Research design choice shows the priorities of the research process (Bryman, 2008). A self-administered questionnaire survey design is the research method, which is a prevalent instrument of data collection method in quantitative research. In social studies, the survey design method has been preferred since it can be generalized from. Moreover, surveys are valuable tools to explain human behaviors in a group or social environment (Bryman, 2008). The researchers utilized a mail questionnaire form to collect data. In the social sciences, survey designs are preferred because of their relation to human perceptions and beliefs.

5. PROPOSED RESEARCH MODEL

In quantitative research, theories and models originate the questions (Creswell, 2009). Thus, the current research is based on a model set forth by Ajzen and Fishbein’s (1975; 1980) describing the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). TRA is used as a framework in several studies about knowledge sharing, including Bock et al.’s (2005), Ibragimova’s (2006), and Tao’s (2008). Moreover, the researchers found consistency with the literature reviews of knowledge sharing practices and Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975; 1980) theory of reasoned action.

Bock et al.’s (2005) model is modified from the original TRA. The modified model deviates from the original TRA with an organizational climate construct and the role of motivational drivers. In addition to attitude and subjective norm, Bock et al. (2005) emphasize that employees are influenced to share knowledge in three broad categories: economic (anticipated extrinsic rewards), social-psychological (anticipated reciprocal

relationships and sense of self-worth), and sociological (fairness, innovativeness, and affiliation).

Ibragimova (2006) substituted extrinsic rewards and reciprocal relation in Bock et al.’s (2005) model with perceived organizational justice constructs. Even while keeping the organizational climate construct, Ibragimova (2006) extended it with rewards, warmth, and support dimensions. These dimensions improve her model in understanding the role of culture and climate immensely.

Tao (2008) made a unique contribution to information seeking behavior studies with a new model, the Information Resource Selection and Use Model (IRSUM), which is based on Fisbein and Ajzen’s (1980) TRA and Davis’ s (1989) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The model proposed uncovering the influence of resource characteristics, individual differences, and the environment of the library as the users select and use information resources (Tao, 2008).

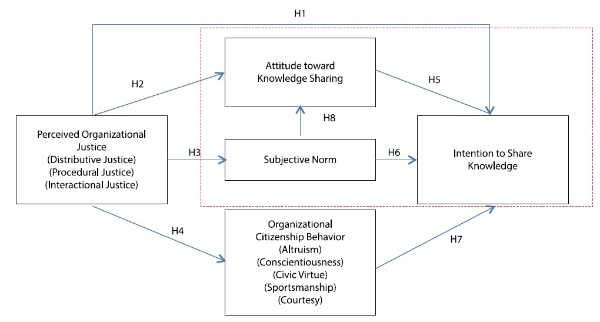

In the proposed model, the researchers integrated perceived organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior constructs within the original TRA constructs, which are attitude toward knowledge sharing, subjective norm, and intention to share knowledge (see Figure 3). Furthermore, the researcher investigated direct and indirect (through attitudes, motivation to comply, and normative beliefs) influence of organizational justice perception on knowledge shar-ing intention. Additionally, this study seeks to find the direct relation of individual characteristics combined under organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) on intention to knowledge sharing. Furthermore, the influence of demographic variables such as gender, post location, education level, role at work, and contract type or rank has been investigated.

Demographic factors are considered as control variables, which are not shown in the proposed model. Four of the constructs in the model are hypothesized to have positive influences on intention to share knowledge.

6. RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

-

RQ1: How do perceived organizational justice, attitudes toward knowledge sharing, subjective norm, and organizational citizenship behavior influence intention to share knowledge?

-

H01: The greater the extent to which perceived organizational justice moves toward being conducive to knowledge sharing, the greater the intention to share knowledge is.

-

H05: The more favorable the attitudes toward knowledge sharing are, the greater the intention to share knowledge will be.

-

H06: The greater the subjective norm is toward knowledge sharing, the greater the intention to share knowledge will be.

-

H07: The stronger the organizational citizenship behavior is, the greater the intention to share knowledge will be.

-

RQ2: How do perceived organizational justice and subjective norm influence attitudes toward knowledge sharing?

-

H02: The greater the perceived organizational justice is, the more favorable the attitudes toward knowledge sharing will be.

-

H08: The greater the subjective norm is toward knowledge sharing, the more favorable the attitudes toward knowledge sharing will be.

-

RQ3: How does perceived organizational justice influence subjective norm?

-

H03: The greater the perceived organizational justice is, the greater the subjective norm to knowledge sharing will be.

-

RQ4: How does perceived organizational justice influence organizational citizenship behavior?

-

H04: The greater the perceived organizational justice is, the stronger the organizational citizenship behavior will be.

7. INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND VALIDATION

The constructs and instrument items used in this study were adopted from previous studies in which the items measuring these constructs were tested and validated (Appendix I). In addition, since Cronbach’s Alpha values for each construct ranged from .75 to .90, the researchers did not see the need to conduct a pilot study to confirm the validity and reliability of the instruments. Research suggests that while there is no cut off point for Cronbach’s Alpha values, over .70 has been accepted as the lower limit in general (Ibragimova, 2006). For example, the score for perceived organization justice demonstrated strong interitem reliability with an α score of .937. All of the items in the instrument used here were measured by a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 5 intended for strongly agree to 1 intended for strongly disagree. The demographic questions formed the last part of the questionnaire.

In this study, endogenous (Dependent) variable is intention to share knowledge. Exogenous (Independent) variables are organizational justice perception, attitude toward knowledge sharing, subjective norm, and organizational citizenship behavior. In addition to these variables, this research consists of five control variables, namely, gender, location of the post, education level, role at work, and type of employment or rank.

As the study is conducted in a Turkish speaking population, translation into Turkish within the context is essential. In order to distribute a clear and understandable questionnaire, two Turkish natives with graduate degrees in information science were asked to translate the survey items into Turkish. A final draft was constructed in Turkish using the two translations. The survey was then given to two different Turkish natives with advanced degrees in sociology and public administration to translate it back into English. The translated and consolidated English version was then compared with the original survey to ensure consistency reliability.

The TNP is the only law enforcement agency in Turkey providing public security service in cities, with more than 200,000 sworn officers and professionals (Tombul, 2011). The organizational structure of the TNP, which is led by the General Director of the Security, is broken down into two main categories: central units and provincial units (Ozcan & Gultekin, 2000). The central units in the TNP establish general strategies, provide technical support, and facilitate cooperation within the organization (Cerrah, 2006).

The Department of Police Forensic Laboratories is one of the central units and has 10 regional laboratories that assist provincial police units and public prosecutors. A forensic laboratory in the TNP is constructed of three basic units: expertise, support, and secretariat units (DPFL, 2012). The expertise units, referred to as core units, are ballistic investigations, document analyzing, chemical investigations, biological investigations, data, voice and image analyzing, and the explosives unit. The support units are budget and supply, training, and human resources units. The secretariat is an administrative unit set up in the headquarters to coordinate relations in the departmental and organizational levels. The population for this study is defined as forensic experts, assistants, and technicians in 10 forensic laboratories established under the Department of Forensic Laboratories in the TNP. The sample size is around 600 people, whose ages, genders, units, and ranks are considered in order to represent the population correctly.

8. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

A total of 536 forensic experts from Turkey National Police Force participated in this study. Most participants were male (87.5%), and 12.5% of participants were female. Most participants earned bachelor degrees (65.1%), 16.6% earned associate degrees, 13.4% earned graduate degrees, and a small minority only had high school diplomas (4.9%). About 22.0% of participants were located in Istanbul, and the rest were distributed according to the following: 15.3% in Diyarbakir, 10.3% in Bursa, 9.5% in Erzurum, 8.0% in Ankara, 8.8% in Izmir, 8.2% in Adana, 7.0% in Samsun, 5.8% in Antalya, and 4.9% in Kayseri.

Participants were divided into 4 groups and categories of rank: constable, commissioned officer, senior officer, and civilian officer. Most participants were constables (83.2%). The rest were distributed as follow: 7.1% were senior officers, 6.9% were commissioned officers, and 2.8% were civilian officers. Finally, the majority of the participating officers occupied specific roles in the forensic branches, namely technicians (54.5%), assistants (25.9%), and experts (19.6%). Each construct was measured on a scale from 1.00 to 5.00 with 1.00 being totally disagree and 5.00 being totally agree. For perceived organizational justice, answers ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 with a mean score of 3.45 (SD = .90). Perceived organizational justice was further divided into three subscores including procedural justice, interactional justice, and distributive justice, where each ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 on the same scale. The mean score for procedural justice was 3.31 (SD = 1.04). The mean score for interactional justice was 3.83 (SD = .91), and for distributive justice, the mean score was 3.22 (SD = 1.02). For attitudes toward knowledge sharing, responses ranged from 1.80 to 5.00 on the same scale with a mean score of 4.07 (SD = .62). For subjective norm, the scores fell within the range of 1.40 to 5.00 on the same scale with a mean score of 3.82 (SD = .64).

Answers to questions about organizational citizenship behavior were measured on the same scale and ranged from 2.13 to 5.00 with a mean score of 4.20 (SD = .43). Organizational citizenship behavior was further divided into five sub scores including altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, sportsmanship, and conscientiousness. Responses to questions about altruism ranged from 1.80 to 5.00 with a mean score of 4.21 (SD = .57). The scores for courtesy fell between 2.00 and 5.00 with a mean score of 4.38 (SD = .50). For civic virtue, scores fell between 2.25 and 5.00 with a mean score of 4.07 (SD = .58). For sportsmanship, scores ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 with a mean score of 4.09 (SD = .71). Participants’ scores for conscientiousness were within the range of 2.00 to 5.00 with a mean score of 4.23 (SD = .59). Finally, scores for the construct intention to share knowledge ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 with a mean score of 4.01 (SD = .74).

Cronbach’s alphas (α) were conducted to determine the inter-item reliability of each of the constructs. Each of the constructs demonstrated adequate reliability (α > .70). The score for perceived organization justice demonstrated strong inter-item reliability with an α score of .937.

Similarly, the α scores for procedural justice, interactional justice, distributive justice, attitudes toward knowledge sharing, and altruism were all above .90 (α = .959, .920, .944, .920, and .905 respectively). The inter-item reliabilities for courtesy, civic virtue, sportsmanship, and intention to share knowledge were also strong with α scores greater than .80 (α = .867, .883, .813, and .833, respectively). Finally, adequate reliability of α > .70 was shown for subjective norm (α = .789), organizational citizenship behavior (α = .759), and conscientiousness (α = .776).

A cross tabulation with Pearson’s chi square (χ2) and Cramer’s V was conducted to test the relationship between the roles of the participants and their levels of education. Results revealed a significant relationship between role and education, χ2 (4) = 143.70, p < .001, V = .366. A greater proportion of participants who obtained graduate degrees (52.8%) were experts compared to participants who obtained either bachelor degrees (18.9%) or high school/associate degrees (.9%). A greater proportion of participants who obtained bachelor degrees were assistants compared to participants who obtained graduate degrees (23.6%) or high school/associate degrees (3.5%). Finally, a greater proportion of technicians had obtained high school/associate degrees (95.7%) compared to technicians who obtained either bachelor degrees (47.3%) or graduate degrees (23.6%).

The main research questions and hypotheses were tested using linear regression techniques. After each of the hypothesized relationships was tested, path analysis was conducted to identify whether the collected data fit the proposed model. The model was tested in two ways. First, the model was tested using just the overall scores for each variable, which included perceived organizational justice, organizational citizenship behavior, subjective norm, intention to share knowledge, and attitudes toward knowledge sharing. When the fit of the data to the proposed model was found to be not adequate, the model was modified. The conceptual relationship among variables was also considered so that intention to share knowledge remained the outcome variable since the purpose of the study was to identify predictors of this outcome.

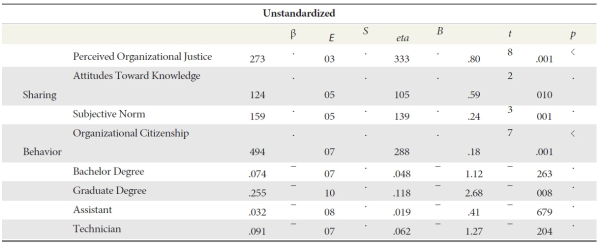

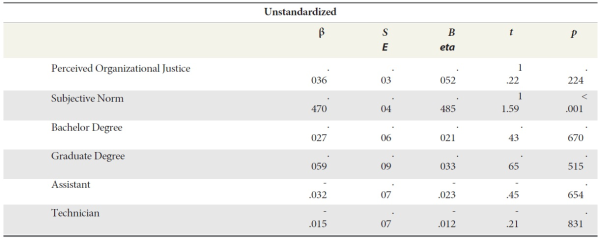

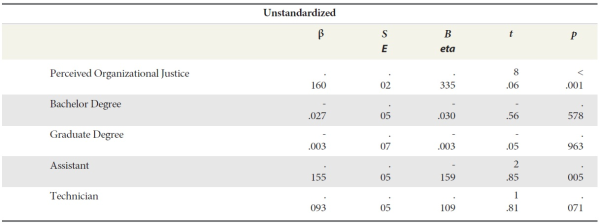

The first multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to predict intention to share knowledge based on perceived organizational justice, attitudes toward knowledge sharing, subjective norm, and organizational citizenship behavior while controlling for education and role. Education and role were found to be significantly related to the other independent variables in the preliminary analysis, so they need to be included in the model to control for their effects. The overall model was significant (F (8, 527) = 49.04, p < .001) and accounted for 41.8% of the variance.

In controlling for education and role, results revealed that higher scores for perceived organizational justice were significantly associated with higher scores for intention to share knowledge (Beta = .333, p < .001). Higher scores for attitudes toward knowledge sharing were associated with increased intention to share knowledge (Beta = .105, p = .010). Higher scores for both subjective norm (Beta =.139, p = .001) and organizational citizenship behavior were associated with increased intention to share knowledge (Beta = .288, p < .001). In addition, it was found that having a graduate degree was associated with lower scores for intention to share knowledge (Beta = -.118, p = .008).

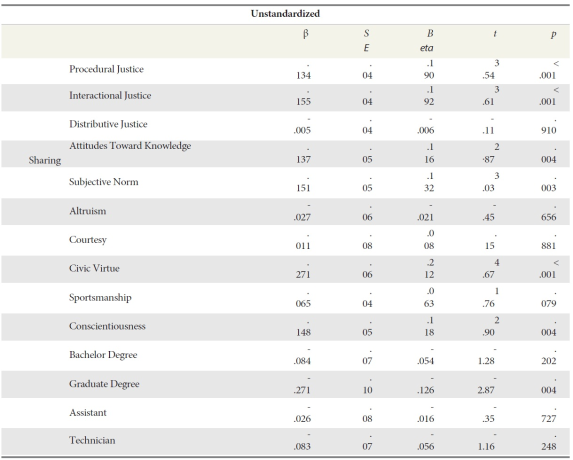

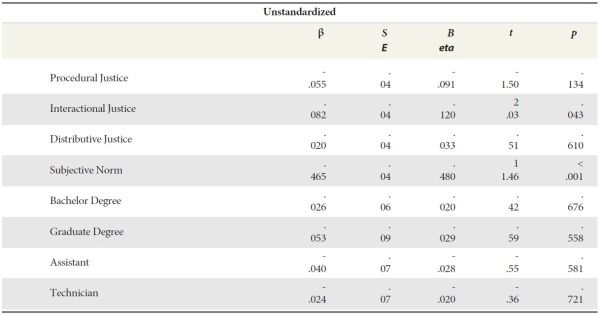

The second multiple linear regression conducted to test the first research question used the sub scores for perceived organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior in place of the overall score. The predictors for this model included procedural justice, interactional justice, distributive justice, attitudes toward knowledge sharing, subjective norm, altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, education, and role. Again, education and role were included to control for their effects on the other predictors.

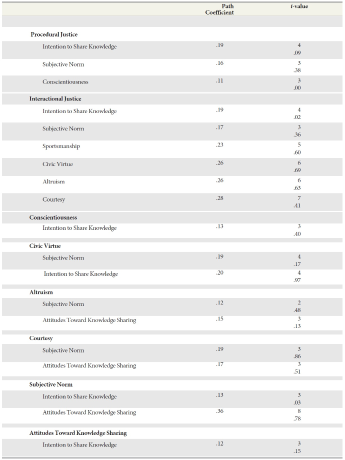

The overall model was significant—F (14, 521) = 30.32, p < .001—and accounted for 43.4% of the variance. In controlling for education and role, results revealed that for perceived organizational justice sub scores, higher scores for procedural justice (Beta =

Table 1.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Intention to Share Knowledge From Perceived Organizational Justice, Attitudes Toward Knowledge Sharing, Subjective Norm, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Education, and Role

Note. F (8, 527) = 49.04, p < .001, adj. R2 = .418

.190, p < .001) and interactional justice (Beta = .192, p < .001) were associated with increased intention to share knowledge. Higher scores for both attitudes toward knowledge sharing (Beta = .116, p = .004) and subjective norm (Beta = .132, p = .004) were also associated with increased intention to share knowledge.

For organizational citizenship behavior sub scores, higher scores for civic virtue (Beta = .212, p < .001) and conscientiousness (Beta = .118, p = .004) were associated with increased intention to share knowledge. Higher scores for sportsmanship were only marginally associated with increased intention to share knowledge (Beta = .063, p = .079). No association was found between intention to share knowledge and either distributive justice (Beta = -.006, p = .910), altruism (Beta = -.021, p = .656), or courtesy (Beta = .008, p = .881). In addition, having a graduate degree was associated with lower intention to share knowledge (Beta = -.126, p = .004).

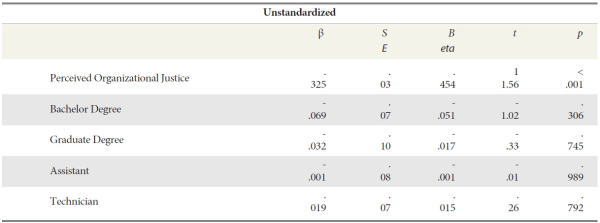

The question on “How do perceived organizational justice and subjective norm influence attitudes toward knowledge sharing?” was also tested using two multiple linear regression analyses. The first regression included the overall scores for perceived organizational justice along with the score for subjective norm. The second regression included the sub scores for perceived organizational justice along with the score for subjective norm.

Education and role were shown to be significantly related to the independent variables in the preliminary analysis and were therefore included in the model to control for their effects. The overall model was significant— F (6, 529) = 31.69, p < .001—and accounted for 25.6% of the total variance. In controlling for education and role, higher scores for attitudes toward knowledge sharing were significantly associated with the score for subjective norm ((Beta = .485, p < .001) but not with the overall scores for perceived organizational justice ((Beta = .052, p = .224).

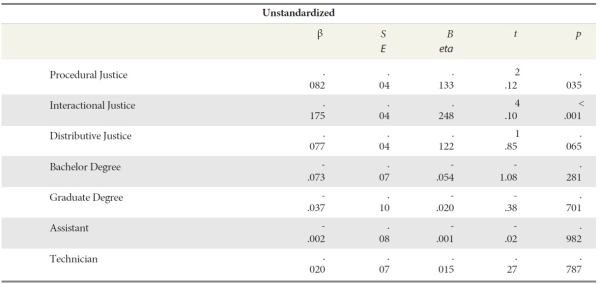

The second multiple regression conducted to test the second research question included subscores in place of the overall score for perceived organizational justice. Predictors of the model included procedural justice, interactional justice, distributive justice, and subjective norm. Again, education and role were included to control for possible effects.

The overall model was significant—F (8, 527) = 24.51, p < .001—and accounted for 26.0% of the total variance. In controlling for education and role, results indicate that both interactional justice (Beta = .120, p = .043) and subjective norm (Beta = .480, p < .001) were significantly associated with higher scores for attitudes toward sharing knowledge. Procedural justice (Beta = -.091, p = .134) and distributive justice (Beta = .033, p = .610) were not associated with attitudes toward knowledge sharing.

The question on “How does perceived organization-

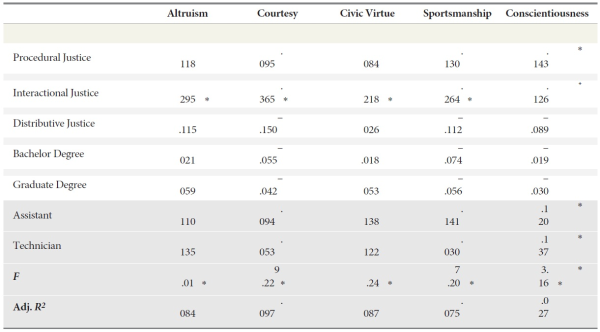

Table 2.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Intention to Share Knowledge From Procedural Justice, Interactional Justice, Distributive Justice, Attitudes Toward Knowledge Sharing, Subjective Norm, Altruism, Courtesy, Civic Virtue, Sportsmanship, Conscientiousness, Education, and Role

Note. F (14, 521) = 30.32, p < .001, adj. R2= .434

Table 3.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Attitudes Toward Knowledge Sharing From Perceived Organizational Justice, Subjective Norm, Education, and Role

Note. F (6, 529) = 31.69, p < .001, adj. R2 = .256

Table 4.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Attitudes Toward Knowledge Sharing From Perceived Organizational Justice, Subjective Norm, Education, and Role

Note. F (8, 527) = 24.51, p < .001, adj. R2 = .260

al justice influence subjective norm?” including its hypothesis, was tested using two multiple linear regression analyses. The first regression included the overall scores for perceived organizational justice, and the second regression included the sub scores for perceived organizational justice. The first multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict subjective norm scores based on overall scores for perceived organizational justice while controlling for education and role.

Education and role were shown to be significantly relative to subjective norm and were included to control for possible effect. The overall model was significant— F (5, 530) = 27.66, p < .001—and accounted for 19.9% of the total variance. In controlling for education and role, results indicate that higher scores for perceived organizational justice were significantly associated with higher scores for subjective norm (Beta = .454, p < .001). The second multiple regression conducted to test the third research question included the sub scores for perceived organizational justice. Predictors of the model included procedural justice, interactional justice, distributive justice, education, and role. Again, education and role were included to control for effects on the dependent variable.

The overall model was significant—F (7, 528) = 20.14, p < .001—and accounted for 20.0% of the total variance. In controlling for education and role, higher scores for both procedural justice (Beta = .133, p = .035) and interactional justice (Beta = .248, p < .001) were significantly associated with higher scores for subjective norm. Higher scores for distributive justice were marginally associated with higher scores for subjective norm (Beta = .122, p = .065).

The question on “How does perceived organizational justice influence organizational citizenship behavior?” including its hypothesis, was tested using multiple linear regression analysis. The first multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to predict the overall scores for organizational citizenship behavior based on the overall scores for perceived organizational justice while controlling for education and role. Education and role were shown to be significantly relative to the independent variables in the preliminary analysis and were therefore included to control for possible effects. The overall model was significant—F (5, 530) = 13.73, p < .001—and accounted for 10.6% of

Table 5.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Subjective Norm from Perceived Organizational Justice, Education, and Role

Note. F (5, 530) = 27.66, p < .001, adj. R2 = .199

Table 6.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Subjective Norm From Procedural Justice, Interactional Justice, Distributive Justice, Education, and Role

Note. F (7, 528) = 20.14, p < .001, adj. R2 = .200

the total variance. In controlling for education and role, higher overall scores for perceived organizational justice were significantly associated with higher overall scores for organizational citizenship behavior (Beta = .335, p < .001). In addition, it was found that being an assistant was associated with higher organizational citizenship behavior compared to being an expert (Beta = .159, p = .005).

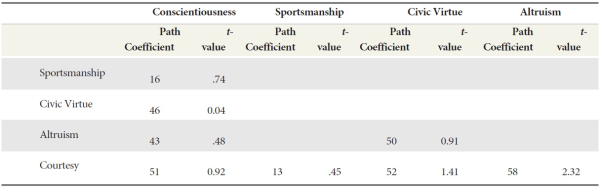

The question was again tested using sub scores for perceived organizational justice to predict each of the five sub scores for organizational citizenship behavior (i.e., altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, sportsmanship, and conscientiousness). Results revealed that all five regressions were significant (all p < .01); the Beta’s and

Table 7.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Organizational Citizenship Behavior From Perceived Organizational Justice, Education, and Role

Note. F (5, 530) = 13.73, p < .001, adj. R2 = .106

regression summary statistics are shown in Table 8.

The percent of variance explained ranged from 2.7% for the model predicting conscientiousness to 9.7% for the model predicting courtesy. In examining the predictors, it was found that procedural justice was only a significant predictor of conscientiousness (Beta = .143, p < .05), indicating that higher scores for procedural justice were associated with higher scores for conscientiousness. Interactional justice was a significant predictor for altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship (Beta = .218 to .365, all p < .01), indicating that higher scores for interactional justice were associated with higher scores for altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship. Distributive justice was a significant predictor of courtesy only (Beta = -.150, p < .05), indicating that higher scores for distributive justice were associated with lower scores for courtesy. In addition, being an assistant or technician was associated with higher scores for many of the organizational citizenship behaviors compared to being an expert.

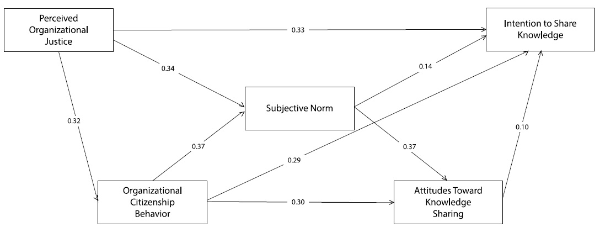

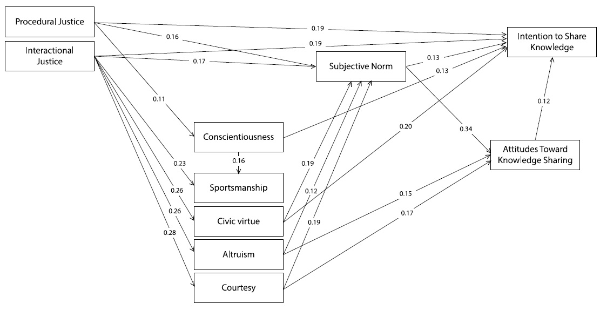

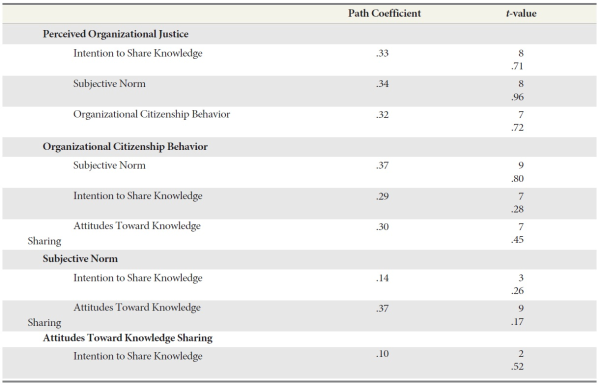

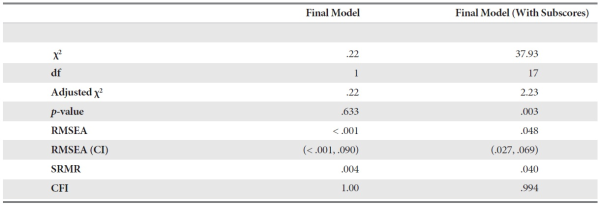

After each of the hypothesized relationships were tested using multiple linear regression, path analysis was conducted using the software LISREL 8.8 to identify whether the collected data fit the proposed model. The model was tested in two ways. First, the model was tested using just the overall scores for each variable, which included perceived organizational justice, organizational citizenship behavior, subjective norm, intention to share knowledge, and attitudes toward knowledge sharing. The fit of the data to this proposed model was not adequate, χ2 (2) = 122.95, p < .001, RMSEA = .337. Therefore, the model was modified according to the fit indices provided by Lisrel. Additionally, the conceptual relationship among variables was also considered so that intention to share knowledge remained the outcome variable because the purpose of the study was to identify predictors of this outcome. The final model is shown in Figure 4 and is summarized in Table 9. This model achieved acceptable fit, χ2 (1) = .23, p = .633, RMSEA < .001. A more detailed list of fit indices for this model and the second tested model discussed in the following paragraphs are presented in Table 10.

In the final model, all paths were significant as indicated by t-values > 1.96, p < .05. Intention to share knowledge was directly predicted by each of the other constructs. In addition, perceived organizational justice predicted organizational citizenship behavior. Subjective norm was also predicted by perceived organizational justice and by organizational citizenship behavior. Finally, attitudes toward knowledge sharing were predicted by organizational citizenship behavior and subjective norm.

Next, the same proposed model was tested using the sub scores of perceived organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior in place of the overall scores. The other variables of subjective norm, intention to share knowledge, and attitudes toward

Table 8.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Altruism, Courtesy, Civic Virtue, Sportsmanship, and Conscientiousness from Procedural Justice, Interactional Justice, Distributive Justice, Education, and Role

Note. + p <.10, * p < .05, ** p < .01

Table 9.

Standardized Path Coefficients and t-Values for Proposed Research Model With Overall Scores

Table 10.

Model Fit Indices for the Three-Factor and Attention/Working Memory (A/WM) Structural Regression (SR) Models

Note. Adjusted χ2 = χ2/df; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = 90% confidence interval; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CFI = comparative fit index

knowledge sharing remained the same. When this model was tested as was proposed, the fit was not acceptable, χ2 (20) = 1395.79, p < .001, RMSEA = .360. This result was not surprising because the simple model in the first test did not show adequate fit either. Therefore, the second model was modified using the modification indices provided by Lisrel and the overall scores as a guide. A well-fitting model was found and is shown in Figure 4 and summarized in Table 10, χ2 (17) = 37.93, p = .003, RMSEA = .048.

As previously mentioned, a detailed list of fit indices is shown in Table 11. Only one sub score (i.e., distributive justice) was eliminated from the model. In addition, the error covariances of several of the organizational citizenship behavior sub scores were allowed to correlate. These correlations are not shown in Figure 4 to make the figure more readable but are presented in Table 11.

In the final model using the sub scores, all the paths were significant as indicated by t-values > 1.96, p < .05. As shown in Figure 5, intention to share knowledge was predicted by all of the constructs except the organizational citizenship behavior sub scores of sportsmanship, altruism, and courtesy. The strongest predictors of to share knowledge were procedural justice, interactional justice, and civic virtue

(Standardized Path Coefficient = .19 to .20). Attitudes toward knowledge sharing was most strongly predicted by subjective norm (Standardized Path Coefficient = .34) but was also predicted by altruism and courtesy. Subjective norm was predicted by civic virtue, altruism, courtesy, procedural justice, and interactional justice. Each of these path coefficients was approximately equal in magnitude (Standardized Path Coefficients = .12 to .19). Of the five organizational citizenship

behavior sub scores, conscientiousness was predicted by procedural justice, and the other four (i.e., sportsmanship, civic virtue, altruism, and courtesy) were predicted by interactional justice. In addition, conscientiousness directly predicted sportsmanship, but sportsmanship did not predict any other constructs in the model.

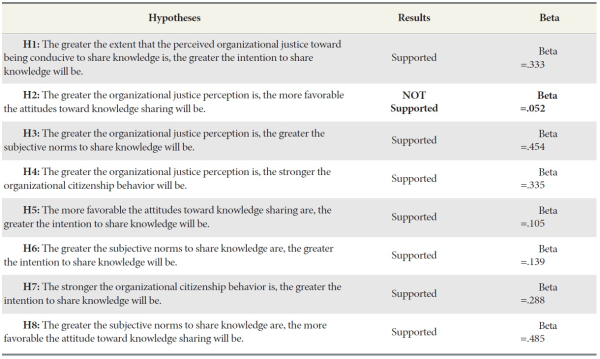

9. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Intention to share knowledge is an individual behavior that is defined as willingness to share one’s knowledge with others within an organization through its repositories, processes, and practices (Bock et al., 2005). Effective knowledge sharing is possible when the parties involved believe that outcomes are distributed fairly and procedures for performance evaluation are conducted justly. Moreover, organizational relationships also encourage employees to share their knowledge with the organization (Ibragimova, 2006). To answer the first research question, “How do perceived organizational justice, attitudes toward knowledge sharing, subjective norms, and organizational citizenship behavior influence intention to share knowledge?” four hypotheses were developed (Figure 3.H1, H5, H6, and H7) developed.

The first hypothesis (Figure 3.H1) examined the relationship between perceived organizational justice and intention to share knowledge. This hypothesis suggested that more positive organizational justice perceptions would promote greater knowledge sharing intentions. Analysis of the data supported this assumption (Beta .333). When looking at sub scores, it was revealed that procedural justice and interactional justice predicted intention to share knowledge but not distributive justice. Thus it supports Ibragimova’s (2006) research. This result highlights that knowledge sharing contributions and efforts can both be reflected to outcomes independently and encourage knowledge sharing. Even though the performance evaluation is fair, employees would engage more in knowledge sharing activities if they see distinct positive outcomes because of knowledge sharing.

Along with subjective norms, attitude toward knowledge sharing is expressed as one of the principal determinants of one’s intentions (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). In terms of TRA, attitudes toward knowledge sharing refer to the level of affirmative feelings a person has, which then determines their intentions. In this study, attitudes toward knowledge sharing are discussed as confirmatory or adverse engagements in sharing knowledge of forensics within the TNP. Furthermore, subjective norms are constructed on two dimensions: normative beliefs and motivation to comply. Constant et al. (1994) emphasized that knowledge sharing increases if members consider it a socially expected behavior in their work environment.

The second hypothesis for this research question (Figure 3.H5) examined the relationship between attitudes toward knowledge sharing and intention to share knowledge. As hypothesized, the data analysis found that there was a significant, positive relationship (Beta= .105) between attitudes and intention to share knowledge; the more favorable the attitudes toward knowledge sharing are, the greater is the intention to share knowledge. Similar to Bock et al.’s (2005) and Ibragimova’s (2006) studies, this research also stressed that attitudes had a positive influence on knowledge sharing intentions. Thus, the finding is consistent with the theory and previous research.

Subjective norms were mentioned as another determinant of intentions. The third hypothesis of the research question, H6 (Figure 3), was tested to examine the relationship between subjective norms and intention to share knowledge. The hypothesis states that subjective norms have a positive effect on intention. Like the earlier research (e.g. Bock et al., 2005; Ibragimova, 2006; Cakar, 2011) and theory, the analysis revealed that the relationship is significant and positive, supporting the hypothesis.

As a motivating factor for a public servant, competition with fellow workers is not apparent all the time due to the nature of service. For instance, law enforcement workers exhibit peer and agency oriented behaviors as part of their subcultural norms. Conversely, in a business environment, employees compete and by demonstrating achievement oriented behavior because outcomes convert responsively to individual gain. Thus, higher employee performance and productivity could be observed as a byproduct of competition. On the other hand, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is defined as work ethics and qualities that are beyond job description. Organ (1988) categorized OCB into 5 aspects: Altruism, Courtesy, Civic Virtue, Sportsmanship, and Conscientiousness. Although OCBs are highly influential on performance and satisfaction at work, they are difficult to acknowledge with standard reward systems (Organ, 1988).

The fourth hypotheses (Figure 3.H7) investigated the relationship between OCBs and intention to share knowledge. Like the earlier research (e.g. Aliei et al., 2011; Al Zu’bi, 2011), data analysis revealed that stronger organizational citizenship behavior would lead to greater intention to share knowledge (Beta= .288). When looking at sub scores, it was observed that civic virtue and conscientiousness predicted intention to share knowledge but not altruism, courtesy, or sportsmanship. The results with sub scores highlighted that loyalty to the organization and respect to the organizational rules are significantly higher than the rest of the OCBs among the forensics in the TNP.

The overall model associated with the first research question was found to be significant with an adjusted (R2=.418). Moreover, in terms of demographic variables, having a high school or associate degree predicted a higher intention to share knowledge compared to having a graduate degree. All results were controlled for education and role.

10. RELATIONSHIPS AMONG EXOGENOUS (INDEPENDENT) VARIABLES

Bock et al. (2005) posit that the roles of anticipated extrinsic rewards, reciprocal relationships, sense of self-worth, and subjective norms should be observed to explain attitudes toward knowledge sharing. Ibragimova (2006) stresses organizational justice perception as antecedent to intention to knowledge sharing. In addition, the relationship between organizational justice perception and attitude toward knowledge sharing were investigated (Ibragimova, 2006).

To answer the second research question, “How do perceived organizational justice and subjective norm influence attitudes toward knowledge sharing?” two hypotheses (Figure 3.H2 and H8) were developed based on the third research question; how does an individual’s perceived organizational justice influence his or her subjective norm? The corresponding hypothesis is in Figure 3.H3.

Ibragimova (2006) emphasizes that perceived interactional justice predicts attitudes toward knowledge sharing but not perceived procedural justice or perceived distributive justice. Hypothesis 2 (Figure 3) examined the relationships between perceived organizational justice and attitudes toward knowledge sharing, finding that the greater the former is, the more favorable the latter will be. Like Ibragimova’s findings, this data analysis showed that the hypothesis was not supported (Beta = .052). Testing the hypothesis with subscores revealed that only interactional justice predicted intention to share knowledge partially supporting the hypothesis.

Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) refer to subjective norms as the importance of expectation that is associated with those who surround an individual in the work environment. Therefore, the people that we work with shape attitudes toward knowledge sharing. The second hypothesis (Figure 3.H8) examined the relationship between subjective norms to knowledge sharing and attitudes toward knowledge sharing. Similar to Bock et al.’s (2005) and Ibragimova’s (2006) findings, the results showed that the hypothesis was supported (Beta =.485).

Bock et al. (2006) argued that there is a significant association between sense of self-worth and subjective norms in the hypothesized direction. In addition, sense of self-worth influences attitudes toward knowledge sharing through subjective norms. Likewise, the results examining H3 showed that there was a positive and moderate relation between perceived organizational justice and subjective norms. This result highlights that forensics have positive feelings from the existing justice in the work place and in fellow employees’ expectations from them.

Matzler et al. (2008) argues that personality traits such as conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness effect knowledge sharing. Al-Zu’bi (2011) emphasizes that sportsmanship, conscientiousness, and altruism respectively have more influence on knowledge sharing than courtesy or civic virtue. The last research question was “How does perceived organizational justice influence organizational citizenship behavior?” Only hypothesis H4 (Figure 3) was tested. Likewise, Aliei et al. (2011) suggested that OCBs are key factors in employee behavior. They highlighted that OCBs have a significant influence on knowledge sharing. Similar to previous research, the results here showed that organizational justice perception promoted organizational citizenship behavior in a posited direction (Beta=.335). When looking at subscores, interactional

justice predicted higher civic virtue, conscientiousness, altruism, courtesy, and sportsmanship. However, distributive justice predicted higher courtesy only. All results were controlling for education and role. Role was a significant predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. Being an assistant or technician predicted higher OCB scores, compared to being an expert.

11. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

This research is the first study to investigate organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior with behavioral intention, as conceptualized using the Theory of Reasoned Action. The empirical evidence provided by this study supports the concept that organizational justice influences knowledge sharing practices within the organization. The study is an attempt to explain perceptions about justice in the work place and behaviors about knowledge sharing with coworkers among forensics experts in the Turkish National Police force. Despite the limitations, the study is an important contribution to the research on organizational justice and knowledge sharing. It is a contribution to both organizational behavior literature and knowledge management literature.

The TRA has been tested in several areas. However, these antecedent factors have not been studied in different sample groups. The study strengthens the theoretical foundation and improved understanding of knowledge sharing practices in the context of organizational factors, including the perception of organizational justice. Moreover, the study provided a comprehensive awareness about the role of organizational justice in the work place.

- 투고일Submission Date

- 2013-12-10

- 수정일Revised Date

- 게재확정일Accepted Date

- 2013-12-14

- 다운로드 수

- 조회수

- 0KCI 피인용수

- 0WOS 피인용수