Library Space and Resource Usage Time: Reflections from Digital Footprints During Pre and Post-COVID-19

Nawapon Kaewsuwan (Department of Information Management, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, and Research Center for Educational Innovations and Teaching and Learning Excellence, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani, Thailand)

Komgrit Rumdon (John F. Kennedy Library, Office of Academic Resources, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani, Thailand)

Abstract

This paper aims to investigate library user behaviors by comparing them pre and post-COVID-19. Two aspects of users’ behaviors were examined, including using physical learning spaces, and online resource utilization. This exploration used secondary data automatically recorded by ALIST OPAC systems (Prince of Songkla University Pattani Campus, Pattani, Thailand) during 2018 and 2022. Descriptive statistics were used to examine physical space usage. The machine learning algorithms name process mining technique was used to investigate the changes in online behaviors, by formulating the sequence of activities based on the digital footprints recorded when users interacted with the systems. This technique exemplified the sequence and timing of activities. The study results revealed an increased use of limited co-learning spaces by library users after COVID-19. The activity of borrowing and returning library resources showed that fewer reminder e-mails on the due date were sent. The process of mining exemplified the sequence and timing of activities. It indicated that after COVID-19, library users hold borrowed items for a shorter time than before the pandemic. These findings suggest that the digital footprints unveiled the changes in library users’ behaviors. That is, the library users return borrowed items faster than in pre-COVID-19 circumstances. A decrease in reminder e-mails was clearly visible to support such a finding. Therefore, it is suggested that library managements should consider a faster operation and well-resourced management to adapt to the changes. Managing resources needs to become faster as the library users showed a potential for faster return of borrowed resources.

- keywords

- library spaces, user behaviors, digital footprints, data mining, process mining, COVID-19

1. INTRODUCTION

The global pandemic of coronavirus, also known as COVID-19, has had great effects in all aspects (Al-maaitah et al., 2021). That is, the dangerous spread of the virus resulted in the restriction of physical social interaction (De Groote & Scoulas, 2021; Marome & Shaw, 2021). Hence, all activities involving human interaction had to be paused. This resulted in the exponential use of technology. Consequently, several new technologies and applications were developed to assist humans in continuing their work (Ćirić & Ćirić, 2021; Yu et al., 2023). People were pushed to adapt to the new way of life. Many become much more comfortable communicating via video conferencing, reading, and working through digital devices. Many resources became available in the digital format. Yet, some were keen on physical interaction and aimed to make up for the time they lost during the shutdown (Wassler & Fan, 2021). The latter is referred to as the ‘revenge user’s effect.’ This term is frequently used in several fields. For instance, revenge tourists were used to explain a surge of tourists after COVID-19 in several countries such as Indonesia (Abdullah, 2021) and India (Joshi & Sadhale, 2022). These surges were influenced by the need for physical travel and to make up for the time people had to stay at home during the pandemic (Wassler & Fan, 2021). This similar situation was expected in various areas such as business, marketing, and education, as well as public spaces and co-working spaces like libraries.

The disruption of COVID-19 changes users’ behaviors (Al-maaitah et al., 2021). In a Thai context, the implementation of movement restrictions, social distancing, and promotion of online working has a significant contribution and is embedded in the new normal routine (Mahapornprajak, 2021; Marome & Shaw, 2021). According to a research survey conducted by Mahidol University (2020), after COVID-19 the Thai population was strongly aware of and positively responded to the campaign to prevent and control the virus spread. Thai citizens paid close attention to social distancing regulations, as reflected by their decision to stay at home or in limited closed spaces, such as a small meeting room, well air-circulated spaces, and limited numbers of entry spaces considered safe from virus spreading. Their study revealed that the Thai population tried to limit time spent in public and crowded spaces such as parks, restaurants, and working spaces as well as libraries (Marome & Shaw, 2021). The studies presented thus far reflect the changes in users’ perceptions and behaviors in general. However, much is unknown regarding the behaviors of users when using the library. It is hypothesized that the behaviors of library users changed after COVID-19. However, to what extent does this change affect the operation of the library? This question remains unanswered.

Before COVID-19, many libraries in Thailand allowed physical borrowing of books at the library to verify the identity of the user, checking out books, and returning of borrowed books. During COVID-19, this operation was replaced with online booking and delivery systems. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research specifically focused on the changes in library users’ behaviors after COVID-19, especially for Thai citizens.

The library is a large source of knowledge and learning space (Unchitti, 2005). The library is managed by many organizations, such as information centers, specialized libraries, national libraries, and public libraries, as well as libraries in educational institutions, including school libraries and university libraries. The library plays an essential role in knowledge acquisition and development for all education levels. Not only does the library provide information, but it also offers other support, including borrowing and returning resources, information management tools, learning and co-working spaces, information searching and management consultations, and many more activities (Kamolpechara & Soopunyo, 2020; Unchitti, 2005).

The growth of technology and the hit of COVID-19 have impacted library usage (Ćirić & Ćirić, 2021; De Groote & Scoulas, 2021). Libraries were forced to close during COVID-19 (Salvesen & Berg, 2021). Several libraries developed online systems to keep their services running and facilitate access to learning resources (De Groote & Scoulas, 2021; Yu et al., 2023). Some developed book and library resource delivery systems to support distance learning (Yu et al., 2023). Not only do these changes affect users in terms of services, but COVID-19 also might impact users’ behaviors. For instance, users might come to prefer reading digital files rather than physical books (Millar & Schrier, 2015). They might also spend more time reading (Alomari et al., 2023). Yet much is unknown regarding user behaviors (Alomari et al., 2023). Hence, it is important to understand the changes in users in order to provide effective services to them (Sangchantr, 2022), especially for university libraries, which offer their services to different groups of users such as higher education students, researchers, academicians, and the public. Studying the university library users’ behaviors recorded by the system is essential for the library to modify its operation to suit the needs and behaviors of its users (De Groote & Scoulas, 2021). This could also provide suggestions on how to allocate resources efficiently. Moreover, user behavior analysis could also lead to the effective use of available resources and reduce unused resources in the long run.

Generally, libraries record a high volume of data (Horstmann & Brase, 2016). Yet this data is still suboptimally used. In fact, the recorded data contain the digital footprint of users when interacting with the system. This is referred to as ‘trace data.’ Several fields of study utilize this data to enhance the process. However, there is a lack of study focusing on trace data obtained from library management systems, much less examination of the changes in user behaviors. By in-depth analysis of the trace data, it is expected that some valuable insights into library users’ behaviors after COVID-19 could be observed. These insights can be utilized to enhance the service quality of university libraries or information service institutions in the post-COVID-19 era, particularly in the process of library operation. Hence, this research aims to bridge the gap by comparing changes in terms of physical space usage and online operation during the pre and post-COVID-19 period. Examining such trace data requires an advanced machine learning (ML) algorithm due to the large volume of data. Therfore, process mining, which was built on ML algorithms to discover the process, was used. Previous study showed that the process mining algorithm enables the best practice in library operation (Dzihni et al., 2019; Kouzari & Stamelos, 2018).

Moreover, the research outcomes and recommendations can be applied in policy and strategic planning for information services, budget allocation, service organization, and online or electronic information dissemination formats that align with the changing behaviors of individuals. These findings can inform the design and provisioning of information services and learning spaces that are suitable and user-friendly. Additionally, they can assist in sharing best practices for data management to enhance future library management systems.

2. OBJECTIVES

To analyze and compare library users’ behaviors before and after COVID-19 by examining physical space usage and online resource usage time.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1. Library Transformation: Traditional Libraries Heading into the Artificial Intelligence Era

Universities often organize their libraries to offer open information resources for users. Traditional libraries are physical institutions that serve as a repository of information resources. They are spaces where users can access print resources such as books, journals, newspapers, magazines, and other materials for educational, recreational, research, and other purposes. These libraries often have several types of spaces: quiet reading areas, individual learning spaces, and collaboration and discussion spaces. There are librarians who assist users in retrieving and utilizing the available information resources and systems (Ashikuzzaman, 2023).

Recent developments in technology have had a high impact on the library, as many users are promptly adapting to digital libraries. This is because these resources are flexibly accessible via the Internet. They are also known as online resources. User behaviors have changed, resulting in an increased number of digital reading materials and digital media. However, university libraries are still considered vital learning spaces. According to Asif and Singh (2020), traditional libraries have been turned into digital libraries due to technical developments. Libraries have a wide variety of e-resources, e-services, and other functions, as well as distributing information in e-formats to meet the information needs of modern library users.

Over the past decade, libraries have developed their activities and affordance with the use of technology. For example, augmented reality and virtual reality, emerging technologies that utilize virtual objects to enhance reality, have been used to improve the library user experience and engagement. Several types of software, applications, and systems have been developed to support the operation of the library and user education (Oyelude, 2017; Yu et al., 2023). Recently emerged generative artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT, have also been integrated into the library system. According to Ehrenpreis and DeLooper (2022), using an AI Chatbot on library websites to answer questions helps retrieve or recommend information sources like a librarian.

3.2. Reading Behaviors

Various unexpected changes have occurred due to the great impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes have affected many sectors, mostly in social, economic, and education domains. Consequently, people were strongly urged to stay home, and even work and study are transformed into online modes (MacKenzie, 2020). Libraries had to be physically closed. To some extent, their services were provided by online systems. At the same time, digital content became the sole option for these libraries’ users (Ćirić & Ćirić, 2021). As a result, user behavior has changed with technology that supports easier access to information, and users can access it anywhere, anytime, through the Internet. As a consequence, the rapid ongoing transition of reading from print to screen is clearly visible. This creates challenges to the use of physical books. At the same time, it creates the opportunity for digital books and reading materials due to an increasing number of digital reading devices, such as computers and laptops, tablets, smartphones, and other forms (Horstmann & Brase, 2016).

The paradigm of reading, in particular for users, is increasingly screen-based rather than paperbound. As Internet use has developed increasingly, more reading information resources have transformed into digital format, gaining more readers through this platform. In contrast, paper-based reading also has its particular benefits, such as time efficiency (Delgado et al., 2018), eye-friendliness (Tosun, 2014), comprehensibility (Duran, 2013; Jabr, 2013), and simplicity (Jabr, 2013). Regardless of the fact that some people refuse to use paper due to the increasing campaign of wasting less paper (Parlindungan et al., 2021), many people still find paper their preferred reading material. Additionally, some research has argued that digital environments may not always be best suited to fostering deep comprehension and learning. For example, Mangen et al. (2013) found that students who read texts in a printed format scored significantly better on the reading comprehension test than students who read the texts digitally. Similarly, Delgado et al. (2018) suggested that providing students with printed texts, despite the appeal of computerized study environments, might be an effective way to improve comprehension outcomes. Therefore, the role of libraries, which contain a large number of paperbound materials, are essential for education.

However, given the unexpected attack of COVID-19, users’ reading behaviors and library usages are expected to change. For instance, Ćirić and Ćirić (2021) found that the average reading time of participants from Serbia increased by approximately 130% during the lockdown. Baharuddin and Mohamad Rosman (2020) further found that information quality and responsiveness are two important factors that predicted potential library e-services utilization during COVID-19. However, these studies focused on the reading behaviors of digital text by using data gathered from a survey. There is a lack of research utilizing recorded trace data to examine the factors or behaviors of library users during the post-COVID-19 era. Hence, this present research aims to investigate how the behaviors of library users have changed from pre- to post-COVID-19.

3.3. Trace Data Analysis

Interaction with the available information systems offered by the library generates a large volume of data. This data is often used to understand the behavior of users in various fields. For example, trace data is recognized as a highly insightful source of information in education (Gašević et al., 2015). It has been reported as a more reliable source as compared to the use of self-report instruments such as questionnaires, interviews, or think-aloud protocols (Srivastava et al., 2022; Zhou & Winne, 2012). Trace data has also been used in business to understand customer behaviors (Kröckel & Bodendorf, 2012). Similarly, it was used to explore the performance conformation of the hospital process (Gao et al., 2020). As presented thus far, trace data records insightful information about users’ interactions that could be used to strengthen the understanding of user interactions with the system.

To understand the library user and analyze activity relevant to the library, trace data could be used. However, trace data records a large amount of data; a simple count might not offer actionable insights to improve an existing activity and its relevant activities. ML as well as data mining algorithms are often used to unveil the insight hidden within the trace data. ML and data mining algorithms are mathematics-based algorithms that can be grouped under the umbrella of AI. It can be programmed to order the computer to automatically retrieve, recognize, identify, classify, or predict some information from the given data set.

One of the ML algorithms used to mine trace data is process mining. Process mining enables automatically creating a process model from event logs without prior knowedge of the process and analyzing the performance of processes, such as identifying bottlenecks, delays, or resource inefficiencies. Originally, this technique was used to analyze and improve business processes by extracting information from event logs and trace data generated by information systems (Janssenswillen et al., 2019). Recent literature also applies such methods to understand the activity flow of the library process. For instance, Kouzari and Stamelos (2018) applied process mining to examine the differences in operational practices across libraries using the same integrated library system. They found that even though two organisation use the same system, there were differences in terms of practices, activities, sequences, and approaches followed in daily tasks. Such findings could be used to improve existing practices. Similarly, Dzihni et al. (2019) used process mining to examine the bottleneck in the helpdesk process of a university’s academic information system. They were able to indentify two activities in the helpdesk process that required improvement, which were activities during input, and seeing the ticket or request.

Despite the usefulness of process mining, to the best of our knowledge there are a very small numbers of research studies using process mining to examine the processes and activities of the library, especially library users’ behaviors that might have changed due to COVID-19. Therefore, this research aims to explore the changes in library users’ behaviors while using the library resources by comparing pre and post-COVID-19. The behaviors of library users were automatically recorded when they interacted with the system. Therefore, two dimensions of library usage were explored, including library physical access and facilities reservation, and online behaviors.

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1. Library Context

This study focused on library user visitation and utilization of the resources provided by the university library. The secondary data from the system’s recorded interactions were used. The library focused on in this study is one of Thailand’s southernmost university libraries. The university has several campuses with their own libraries. The library offers services to several types of users, including academics, researchers, graduates, undergraduates, university employees, and external university users, including adults and children. There are eight main faculties offered on the campus. Library users can physically visit the library during working hours from 8:30 to 20:30 daily. During examination weeks the library offers 24-hour access. When users pass through the entry gate, the automated system will read the ID and start counting the entry.

The university’s library offers a variety of resources. This includes paperbound and digital-based reading materials, audio and video materials, computers, working spaces, meeting rooms, discussion rooms, and electronic devices (Prince of Songkla University Pattani Campus, n.d.). Some of the resources are made available via online systems. Some resources are physically available at the library. This study focused on items that were made available to physically borrow at the university, such as paper-based books, meeting rooms, and facilities.

However, borrowing items from the library must be done through an electronic system. In general, graduates and external users can borrow these resources for seven days. They can renew the borrowed resources by themselves via the online system. All borrowed items need to be physically returned to the library by a specific time or else the user will be fined. Undergraduate students, university employees, and academicians are allowed to borrow items for 30 days and renew them through the online system. In 2018, the renewing function was limited to one time per item. However, in 2022 multiple renewals were allowed. An e-mail reminder will be automatically sent to users if they approach the due date.

4.2. Data Analysis

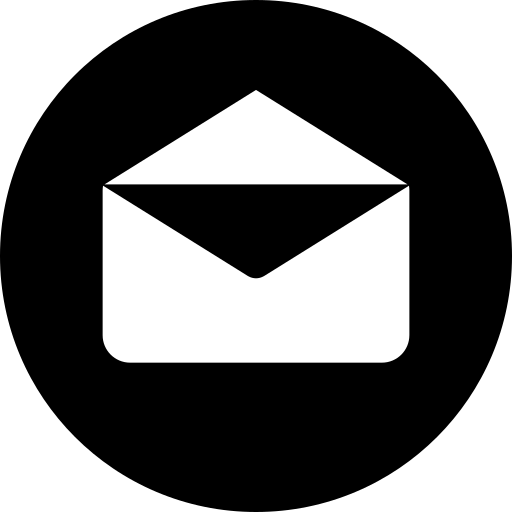

A large volume of data is recorded via the library system. The collected data in 2018 and 2022 were used to understand the behaviors of library users during pre- and post-COVID-19. The data were integrated from several resources to analyze the user’s digital footprint left behind when interacting with the library systems. Fig. 1 presents the relevant sequence of the use of library resources.

Fig. 1

Sequence diagram illustrating sequences and supported systems relevant to this study (own data processing).

Physical entry to the library was recorded by using the university’s self-developed system, called the ASSO system (Prince of Songkla University Pattani Campus, Pattani, Thailand). Only anonymized IDs and the number of times users performed specific actions, such as accessing the library or checking out items, were used in this study. The reservations for meeting rooms, collaborative working spaces, computers, and other facilities were recorded via the room booking system. Only anonymized IDs and a number of reservation counts were used. Borrowing and returning the items are operated via the university’s self-developed system, called ALIST OPAC (Prince of Songkla University Pattani Campus, Pattani, Thailand). Log data recording the user’s interaction with the system was used. Based on the exploration, the main learning events recorded by the system included check-in items, check-out items, reminder e-mails, and renewal items. Also, some minor events were recorded, such as inserting, updating, deleting the remark, holding, canceling the hold item, and reporting the lost item. A brief description and its corresponding event are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Event and description of events recorded by the online library system (own data description)

| No. | Activity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check-out item | A user borrowed and checked out the item from the library |

| 2 | Check-in item | A user checked in and returned the book to the library |

| 3 | Reminder e-mail | The library system sent a reminder e-mail about the due date of the borrowed item to the corresponding user |

| 4 | Renew item | A user renewed the borrowed item and extended the due date |

| 5 | Update due datetime | The system updated the due date manually |

| 6 | Insert block message | A user inserted a remark note |

| 7 | Delete block message | A user deleted a remark note |

| 8 | Update check-outs note | A user updated the check-out remark note |

| 9 | Hold item | A user queued to borrow a specific item |

| 10 | Cancel hold item | A user canceled the queue |

| 11 | Lost item | A user reported a lost item |

To prevent any identification of library users, only the anonymized ID, corresponding department, type of user, events, borrowed items, and timestamp were used to understand the behaviors of the users.

The university library recorded a huge amount of data; hence, to understand the users’ behavior extensively, the ML algorithm was used to analyze the data. In this study, process mining was used to formulate the sequence of activities of library users. Before applying process mining, the trace and its sequences were explored by the bupaverse R package (Janssenswillen et al., 2019). The trace explorer function enables us to visualize sequences within the coverage ranges, most frequently observed sequences, and infrequent sequences. Then, the bupar R library (Janssenswillen et al., 2019), one of the most frequently used R libraries, was used to explore the activities and sequence of activities.

The sequence of activities was illustrated by using a directly-follows graph (DFG). DFG is the simplest and most commonly used method to formulate the process based on the occurring event (Van Der Aalst, 2012). It simply requires an activity instance, sometimes referred to as case, activity, and timestamp. Some other variables are optional when computing the diagram. To address the research aim, the sequence of activities performed by library users was formulated for each iteration of the borrowed item by each user. Hence, the case variable referred to any related events performed by a user from borrowing until returning the specific item. The activity referred to the event recorded in the system as presented in Table 1. The timestamp refers to the specific time when the event occurred.

As a result of using DFG via bupaR R library, the sequence of activities was illustrated. It is composed of nodes, numbers, and flows (arrows). Each node represents each activity, as presented in Table 1. The flows of activities were illustrated by using the arrows to represent the direction from the source activity to the next activity. Hence, the behaviors derived from user interactions prior to COVID-19 and after COVID-19 can be examined.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Accessing and Facilities Reservation

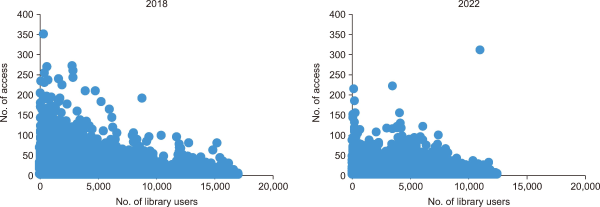

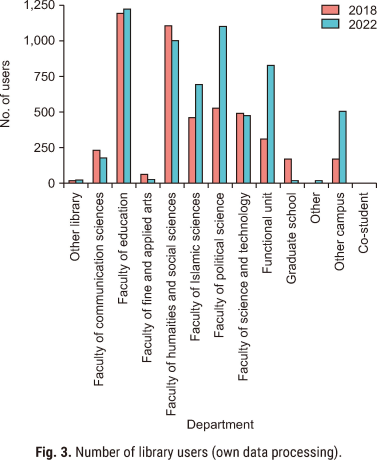

Exploration into library usage before and after COVID-19 revealed a decreased number of library users. Prior to the global pandemic, 9,674 library users physically visited the library in 2018. The majority of them were undergraduates (5,314, 54.93%), academics and researchers (3,394, 35.08%), external university users (397, 4.10%), graduates (328, 3.39%), and university employees (242, 2.50%). A total number of 192,920 counts were recorded for physical entry to the library. The average number of visits was 11.33 times. However, in 2022 after the global pandemic, the number of library users who physically visited the library decreased to 7,511. Similarly to the pre-COVID-19 period, most of them were undergraduates (4,442, 59.14%), academics and researchers (2,164, 28.81%), external university users (654, 8.71%), graduates (189, 2.52%), and university employees (62, 0.82%). The visitation counts came to 94,768 times. The average number of visits was 7.57 times. The distribution of visitation counts showed similar patterns, as presented in Fig. 2.

Even though the number of visits decreased, the number of meeting rooms and co-working space reservations increased. That is, in 2018, 675 reservations were recorded in the database. In 2022, the number of reservations increased to 1,552.

When looking into online behaviors (refer to Fig. 3), it was revealed that most library users were undergraduate students enrolled in the faculty of education, humanities and social sciences, and political sciences. In 2022, there was a very large increase in library users from the faculty of political sciences, the faculty of Islamic sciences, and those from functional units as well as from other campuses.

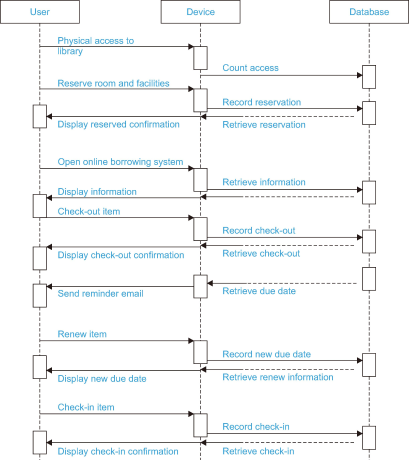

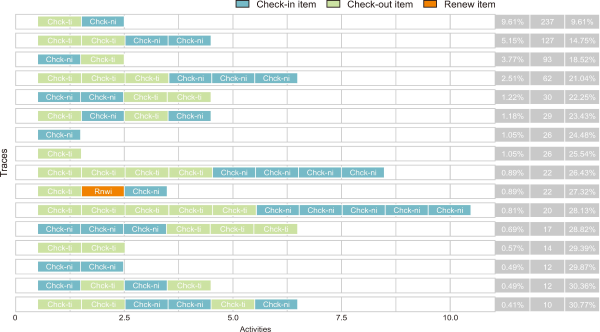

5.2. User Behaviors When Interacting with the Online Library System

Fig. 4 presents the sixteenth most frequently occurring sequences of interaction exhibited by library users. These sequences covered 13% of all sequences. As shown in Fig. 4, the most frequently observed sequence was checking out items from the library and returning the items. Other patterns that frequently occurred were checking out items from the library, followed by the reminder e-mail regarding the due date, and then returning the item to the library after receiving the reminder e-mail. When looking at the whole diagram, it is clear that e-mail reminders were the most frequently occurring event when interacting with the ALIST system, as presented in Fig. 5. The node in Fig. 5 represents the type of interaction with the ALIST system. The darker shade of node color represents the higher records of such interactions. The percentage in the node indicates the proportion of interaction against all recorded interactions. The numbers located inside the node show the actual number of recorded interactions. The arrow indicates the flow of the activity from the one interaction and its following interaction. The stronger and thicker the line signifies the higher frequency of occurrence and vice versa.

Fig. 5

Overall activity sequence of user interaction with the online library system in 2018 (own data processing).

In 2018 (refer to Fig. 5), most library users began their activity by borrowing items (start → check-out item) from the library. Note the beginning of interactions by returning the borrowed items (start → check-in item) to the library, as this action might be a result of continued activity from the previous year. The proportion of interactions between checking-in (check-in item → check-out item) and checking-out items (check-out item → check-in item) from the library is almost equal (22.31% and 22.80%, respectively). This indicates that the user will normally borrow the items from the library and return them after some time. However, the strongest, darkest shade of nodes is the reminder e-mail (accounting for 41.86% of all recorded interactions), showing a strong direction to check-in (reminder e-mail → check-in item) and check-out (reminder e-mail → check-out item) of items from the library. This means that most of the time, library users receive a reminder e-mail regarding their borrowing, returning, and due date of the items.

Similar to 2018, in 2022 the most frequently occurring activities were checking out items from the library and returning the items to the library. This sequence accounted for 9.61% of all detected sequences. Also, library users often borrowed multiple items at a time, as indicated by consecutive check-outs followed by separate check-ins. The main difference observed was that in 2022, the number of e-mail reminders to return books was much lower than in 2018. The interaction of renewed items was also observed in the 16 most frequently observed sequences (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Sixteenth most frequently occurring activity in 2022, covering 31% of sequences (own data processing).

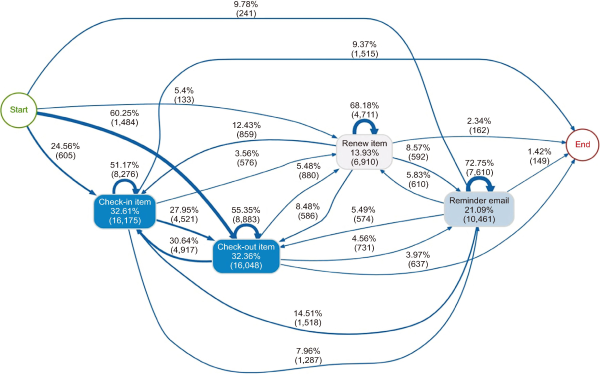

Fig. 7 presents the overall sequence of activities based on library users’ interactions when borrowing items from the library in 2022. Note that the number of interactions was slightly lower than in 2018. This is due to the smaller number of library users in 2022 as compared to 2018. Hence, the percentage of proportion is better for representing user interactions with the online library system. Similar to 2018, most library users began their interaction with the system by checking out the item (start → check-out item), accounting for 60.25% of initial interactions in 2022. Unlike in 2018, the library users’ check-in and check-out items were much more in number of items, as presented in Fig. 7. There was a strong connection between check-in and check-out items from the library (check-in item → check-out item; check-out item → check-in item). The proportion of e-mail reminders was two times lower than the proportion of reminder e-mails observed in 2018. Meanwhile, the number of renewed items was also higher.

Fig. 7

Overall activity sequence of user interaction with the online library system in 2022 (own data processing).

6. DISCUSSION

The exploration of entry and room reservations showed a higher number of users accessing the library in 2018 compared to 2022. However, the number of room reservations in 2018 was much lower than in 2022. This showed that users utilized several learning spaces offered by the library, such as a common space, quiet reading space, learning space, meeting room, and computer room. This aligns with several research studies indicating that the library does not only represent a repository of information but also offers knowledge sharing (De Groote & Scoulas, 2021; Yu et al., 2023), learning resources (Gambles, 2016), a creativity atmosphere (Mahidol University, 2020), and discussion spaces between users (Gambles, 2016; Matichon Public, 2017). Students often visit the university library while waiting for their next class (Unchitti, 2005).

The high number of entries in 2018 reflected that before COVID-19, library users were comfortable using the common learning spaces and library facilities at their convenience. However, the higher numbers of room reservations in 2022 showed that rather than spending time in a common space like before the COVID-19 outbreak, library users preferred to book a limited closed space by booking specific rooms. This is different from the situation in tourism where revenge users surged out after COVID-19 to spend time traveling, compensating for the time they had to spend at home. The library users behaved differently. Users spent time in the library but preferred to book private group learning spaces. One of the possible reflections that can be observed from this finding is that Thai university library users were aware of and continued to take precautions to minimize the risk of being exposed to the virus. This is aligned with the study from Mahidol University (2020), which found that in the post-COVID-19 era, many populations in Thailand have increased their awareness of the virus and infections. They complied and positively responded to the campaigns to reduce and control the spread of the virus.

Among the campaigns promoted by Thailand authorities during COVID-19 were keeping social distance, reducing risk by not being in a crowded space, working in a small group in a closed space with well-air circulation systems, and many other strategies. The post-COVID-19 situation from this study reflects that library users adapted and felt more comfortable using the limited closed collaboration space rather than common space as in pre-COVID-19 situations. As a result, the number of room reservations in 2022 for group meetings within the library has increased accordingly. This is also consistent with Wongmonthar (2021), who found that after the COVID-19 outbreak, people need to be attentive to their health and focus on protecting themselves in order to survive by changing their behavior. By living a life that deviates from the old ways of life by building and adjusting to a new way of living, such as changing behavior by refraining from participating in activities with numerous people, and isolating from places where there are large gatherings or gatherings of people, private and careful use of space has increased.

The most striking finding from this study was the activity of borrowing and returning the resources of library users. Process mining revealed that a large volume of reminder e-mails was sent out prior to COVID-19. A higher number of reminder e-mails is linked to the high volume of library visitors during 2018. Hence, the proportion of events was calculated in relation to all recorded data in that year. Reminder e-mails accounted for 42% of all recorded data in 2018, while only 21% was observed in 2022. Reminder e-mails aimed to remind library users regarding the due date of their checked-out resources. The higher frequency of e-mails indicated the higher numbers of library users who prolonged their return of borrowed items. This shows that library users have neglected to return their books to the library. This may have been influenced by personal traits of library users, such as procrastination behaviors, losing a book, forgetting, or lack of social responsibility. In addition, the reason for higher e-mail notifications for users to return books may have been due to the fewer restrictions on visiting the library physically before COVID-19. Hence, library users may not pay attention to the due date as they can easily re-borrow the borrowed resources at any time via the ALIST OPAC system, as well as physically visiting the library.

The smaller proportion of e-mails in 2022 indicated that there was a lower number of e-mails sent to remind of due dates. This showed that users returned books prior to the due date. Hence, no reminder e-mails were sent out in a large number of activities. Many users spent less time holding the borrowed printed resources. This might indicate that users read books or printed resources faster, which resulted in the activity of returning books faster. As claimed by Alomari et al. (2023), based on study on the impact of COVID-19 confinement on reading behavior, it was found that due to the outbreak and quarantine measures, including self-quarantine, physical distancing, prohibition of group activities, school closures, and lockdowns, people changed their behavior. They were more enthusiastic about reading than before, approximately 15% more. They found that people spent time on reading, approximately more than three hours per person. Similarly, Madani et al. (2020) also found that during COVID-19, approximately 15% of participants read more than three hours daily. Apinunmahakul et al. (2023) posited that this may have been due to a change in users’ behaviors, because they were accustomed to spending more time by themselves, which resulted in the habit of spending more time reading. In addition, various activities that used to take place and fill time, such as field trips, social gatherings, and traveling to various places before and during the COVID crisis, such as homes, educational institutions, entertainment venues, and tourist attractions, have disappeared. Hence, many people replaced their spare time with reading or other activities that can be performed at home. Hence, the reading capacity has increased.

7. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Implications for practices derived from this research will help service operations of university libraries, school libraries, public libraries, specialized libraries, and information service institutions to be able to apply them to increase service quality in accordance with the needs of library users. Implications for practices are threefold. Firstly, physical space is still an important element in the library. Regardless of the prior or post COVID-19 effects, university library users still use the library spaces immensely. The physical space needs to be well-managed and well-allocated to suit the needs of library users. The current study suggests that in being aware and taking precautions in 2022, many university library users preferred limited private group working spaces to discuss, share, and collaborate with their peers. The supported systems that allow flexible access and reserving of the learning spaces offered by the university’s library have increasingly been used in recent years. Nonetheless, the arrangement and allocation of the library space need to be well-managed. Several previous studies suggested that to support learning activities (Kaewurai & Chaimin, 2019), the library should include:

8. LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The dataset used in this study considered data from two years, 2018 and 2022. Hence, some actions might be a sequence of the previous year’s activities. For example, library users might borrow items in December of the previous year and return the item in January. However, this study takes all activities equally as long as they happen in 2018 and 2022.

Secondly, this research employed only the automated recorded data. Even though recorded data reflected users’ interactions and activities within the system, it does not provide the rationale for user’s behaviors. Asking the users about their perceptions through a survey or questionnaire would provide additional information. The questionnaire might also offer some insights into the reason behind users’ actions.

Thirdly, the automated record system is subject to electricity and Internet availability. Therefore, some data might be lost when electricity or the Internet malfunction.

Lastly, some external factors might influence the use of library services, such as the persuasiveness of instructors, the number of students in each faculty, the number of librarians, and other variables. However, this study only focused on online behavior regardless of these factors. Additionally, physical behaviors and direct interaction with librarians were outside of this study’s scope. Future work should also focus on these factors and examine their influence on library users’ behavior.

9. CONCLUSION

This paper explores the behaviors of library users pre and post-global pandemic. The results from the trace data revealed that the number of entries to the university library after COVID-19 was lower than in 2018. However, the number of room reservations increased. This indicated that after COVID-19, users prefer using private and closed spaces. The results from process mining revealed that the time users held borrowed books was shorter than the time they previously held items before COVID-19. One of the posible explanation might be users developing reading skills and spending less time reading. Hence, the sequence of activities from borrowing to returning or renewing the borrowed resources was shorter. This has resulted in reducing the frequency of reminder e-mails sent out by the system. The changes in number of reservations and behaviors suggests that the library needs to take into account the importance of physically closed private spaces. The faster time of returning books indicates the likelihood of borrowing the new resources; hence, librarians need to ensure that the process and activities are able to cope with the speed of the users. The use of ML and data mining algorithms is beneficial. It enables us to unpack the valuable insights hidden within the trace data.

REFERENCES

, , , (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the electronic commerce users behavior Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27, 784-793 https://cibgp.com/au/index.php/1323-6903/article/view/599.

, , , (2023) The impact of COVID-19 confinement on reading behavior Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 19, e174501792304260 https://doi.org/10.2174/17450179-v19-e230505-2022-42. Article Id (pmcid)

, , (2015) Library learning spaces: Investigating libraries and investing in student feedback Journal of Library Administration, 56, 647-672 https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105556.

, , (2023) Impact of COVID-19 on primary school children's learning Journal of Applied Economics and Management Strategy, 10, 51-69 https://kuojs.lib.ku.ac.th/index.php/jems/article/view/4893.

(2023) Traditional library https://www.lisedunetwork.com/traditional-library/

, (2020) Trends, opportunities and scope of libraries during COVID-19 pandemic IP Indian Journal of Library Science and Information Technology, 5, 24-27 https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijlsit.2020.005.

, (2020) Factors affecting the usage of library e-services in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic Academic Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 4, 1-14 https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/42534/.

, (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on digital library usage: A public library case study Journal of Web Librarianship, 15, 53-68 https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1913465.

, (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on the use of the academic library Reference Services Review, 49, 281-301 https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2021-0043.

, , , (2018) Don't throw away your printed books: A meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension Educational Research Review, 25, 23-38 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003.

(2013) Efficiency in reading comprehension: A comparison of students' competency in reading printed and digital texts Educational Research and Reviews, 8, 728-739 https://academicjournals.org/journal/ERR/article-abstract/74855B46066.

, , (2019) Business process analysis and academic information system audit of helpdesk application using genetic algorithms a process mining approach Procedia Computer Science, 161, 903-909 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.11.198.

, (2022) Implementing a chatbot on a library website https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1400&context=le_pubs

(2016) Future city, future library: Experiences and lessons learned from the library of Birmingham https://news.npru.ac.th/u_news/detail.php?news_id=22397&ref_id=LIBRARY

, , , , , (2020) Understanding urban hospital bypass behaviour based on big trace data Cities, 103, 102739 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102739.

, , (2015) Let's not forget: Learning analytics are about learning TechTrends, 59, 64-71 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-014-0822-x.

, (2016) Libraries and data - Paradigm shifts and challenges Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 40, 273-277 https://doi.org/10.1515/bfp-2016-0034.

(2013) Why the brain prefers paper Scientific American, 309, 48-53 https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1113-48.

, , , , (2019) bupaR: Enabling reproducible business process analysis Knowledge-Based Systems, 163, 927-930 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2018.10.018.

, (2022) Revenge tourism: An overview of the phenomenon in India Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 1, 1-5 http://www.mahratta.org/CurrIssue/2022_March_Spl-1/1.%20Revenge%20Tourism%20an%20overview%20of%20the%20phenomenon%20in%20India-%20Miss.%20Aditi%20Joshi,%20Mrs.%20Manasi%20Sadhale%20.pdf.

, (2019) Learning space for digital natives in academic library Journal of Education and Innovation, 21, 366-378 https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/edujournal_nu/article/view/152965.

, (2020) Current scenario of university libraries to enhancing lifelong learning TLA Research Journal, 13, 80-95 https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tla_research/article/view/243184.

, (2018) Process mining applied on library information systems: A case study Library & Information Science Research, 40, 245-254 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.09.006.

(2020) COVID-19 goes global New Scientist (1971), 245, 7 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30424-3.

, , (2020) The psychological impact of confinement linked to the coronavirus epidemic COVID-19 in Algeria International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 3604 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103604. Article Id (pmcid)

(2021) COVID accelerates business transformation into digital https://www.bot.or.th/th/research-and-publications/articles-and-publications/articles/Article_24Apr2021.html

Mahidol University (2020) Behavior of Thai people during COVID-19 become to New Normal https://op.mahidol.ac.th/rm/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Infographic-New-Normal-after-COVID19_May2020.pdf

, , (2013) Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 61-68 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002.

, (2021) COVID-19 response in Thailand and its implications on future preparedness International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1089 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031089. Article Id (pmcid)

Matichon Public (2017) Thammasat University open creative space for startup district https://www.prachachat.net/sd-plus/sdplus-sustainability/news-78749

, (2015) Digital or printed textbooks: Which do students prefer and why? Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 15, 166-185 https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2015.1026474.

(2017) Virtual and augmented reality in libraries and the education sector Library Hi Tech News, 34, 1-4 https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-04-2017-0019.

, , (2021) Academic reading preferences and behaviors of Indonesian undergraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic https://www.elejournals.com/tij-2021/tij-volume-16-issue-4-1-2021/.

Prince of Songkla University Pattani CampusLibrary services for student https://www.oas.psu.ac.th/student/

, (2021) "Who says I am coping": The emotional affect of New Jersey academic librarians during the COVID-19 pandemic Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47, 102422 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102422. Article Id (pmcid)

(2022) Preparedness of library and information services in New Normal: Thai libraries experience TLA Bulletin, 66, 21-36 https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tla_bulletin/article/view/256267.

(2014) A study on reading printed books or e-books: Reasons for student-teachers preferences Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 13, 21-28 https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1018172.

(2012) Process mining Communications of the ACM, 55, 76-83 https://doi.org/10.1145/2240236.2240257.

, (2021) A tale of four futures: Tourism academia and COVID-19 Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100818 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100818. Article Id (pmcid)

(2021) New Normal: A new way of living-with-COVID 19 culture Rusamilae Journal, 42, 47-62 https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/rusamelae/article/view/251056.

, , (2023) Operation management of academic libraries in Hong Kong under COVID-19 Library Hi Tech, 41, 108-129 https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-10-2021-0342.

, (2012) Modeling academic achievement by self-reported versus traced goal orientation Learning and Instruction, 22, 413-419 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.03.004.

- Submission Date

- 2024-02-07

- Revised Date

- 2024-09-12

- Accepted Date

- 2024-10-15